A temple of sonic haecceities

Abstract

Dia:Beacon is a large contemporary art museum in upstate New York that exhibits minimalist, conceptual and post-minimalist art by significant American and European artists, who were most active in the second half of the twentieth century. This paper investigates sonic and durational experiences that formed a major part of my encounter with three artworks: Gerhard Richter’s 6 Gray Mirrors (2003); Robert Ryman’s Installation at Dia:Beacon (2010) and Max Neuhaus’s Time Piece Beacon (2005). I explore how framed experiences of sound and duration (which I qualitatively endured) enable experiential insights not readily available through spatial and visual modalities.

Introduction

Dia:Beacon is a large contemporary art museum in upstate New York that exhibits minimalist, conceptual and post-minimalist art by significant American and European artists, who were most active in the second half of the twentieth century. These works, with their framings of reduced content, caused spatial and durational encounters that emphasised different acts of experiencing. The title of this paper alludes to my perceiving of sounds and pure durational experiences that were surprising, occasionally disconcerting and even distracting to me. In retrospect I consider that my endurance of these temporal encounters opened up an awareness of the role of sound in durational framing within my experiences of the artworks, and thus within experience itself. This essay considers insights revealed through durational and sonic experiences of the Dia:Beacon artworks that might not be available through spatial and visual modalities. The artworks are Gerhard Richter’s 6 Gray Mirrors (2003), Robert Ryman’s Installation at Dia:Beacon (2010) and Max Neuhaus’s Time Piece Beacon (2005).

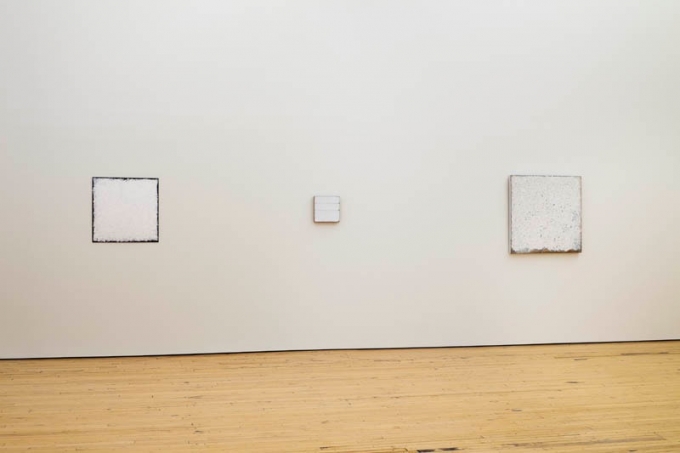

Fig. 1. Gerhard Richter, Six Gray Mirrors, 2003. Dia Art Foundation; Gift of Louise and Leonard Riggio and Mimi and Peter Haas. © Gerhard Richter. Photo: Bill Jacobson Studio, New York

Fig. 1. Gerhard Richter, Six Gray Mirrors, 2003. Dia Art Foundation; Gift of Louise and Leonard Riggio and Mimi and Peter Haas. © Gerhard Richter. Photo: Bill Jacobson Studio, New York

Richter’s 6 Gray Mirrors is situated in a single room in which six large gray mirrors hang as rectilinear repetitions on the four walls. They have a uniform, gray, industrial finish, perhaps reminiscent of a Donald Judd artwork. The forms are called mirrors but also reminded me of paintings. As gray mirrors, their opaque surfaces reflected portions of a gray world beyond their two-dimensional surfaces, including reflections of the viewer and the opaque clearstory windows within his space. Their large forms appeared minimalist and monumental. With the absence of anyone else in the room, seeing myself in the mirrors I felt that I was the focal point of an omnipresent and unknowable panoptic gaze.

After some time, I became aware of sounds coming from beyond Richter’s room. These were sounds of other visitors moving in unseen spaces, the constant hissing of air vents, doors slamming and sounds emanating from other artworks throughout Dia:Beacon. I also heard the rumble of trains passing close by.

While encountering Richter’s installation I became aware of a small stone lodged in the tread of my right shoe. Without thinking, I quickly scuffed my foot on the floor to free the stone. This barely-considered action propelled the stone across the polished concrete floor at great speed. The stone hit a thin metal skirting board along the wall’s edge with unexpected force, causing a sharp, loud snapping sound that reverberated off all the hard surfaces. Initially, I was not sure what had happened. It was as though the room itself had produced a moment of self-articulation.

Robert Ryman’s Installation at Dia:Beacon

Figures 2,3,4. Robert Ryman, Installation at Dia Beacon, installation view, Dia:Beacon. The Greenwich Collection, Ltd. ©Robert Ryman/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Bill Jacobson Studio, New York. Courtesy the Greenwich Collection, Ltd.

Robert Ryman’s Installation at Dia:Beacon is spread over five rooms, variously sized, that can be visited in succession. Thirty-two predominantly white paintings hang on white walls, individually and in groups. One large painting sits on the floor. Ryman’s title suggests that the artwork is an installation in its entirety, but it nonetheless consists of an installed collection of paintings. For a naive visitor - that is, someone who (like me) was relying on intuition rather than any prior knowledge of what to expect - it was apparent that many of the paintings surfaces had no discernible figure, symbol or expressive content. Their framed spatial voids caused confusion. The ‘empty’ paintings appeared to be collectively surveilling me. It was unnerving.

The experience of whiteness was immersive. Ryman comments in a 1986 interview in Art News that, “the white is just a means of exposing other elements of the painting … White enables other things to become visible” (Colaizzi & Schubert, 2009). The colour white, then, allows the viewer to look through and beyond or into the paintings’ surfaces, in search of these “other things”. For me, the effect of this whiteness was both spatial and durational. It suggested the experience of noise; ‘white noise’ in particular, which, technically, is a type of sound comprised of all possible frequencies heard simultaneously, over a given bandwidth (Brown 1983). White noise can be compared to the colour white, which itself contains all possible frequencies of the visual spectrum. The quality of white noise as sound is experienced as a featureless thick hissing that appears to surround the listener. White noise is omnipresent because, by its very definition, it contains no information, and so provides no sonic perspective, direction or sense of depth. It is uncoded. Noise does however contain duration and creates sensation.

Max Neuhaus’s Time Piece Beacon

Fig. 5. Entrance to Dia:Beacon. Photo: David Chesworth

Fig. 5. Entrance to Dia:Beacon. Photo: David Chesworth

Later in the afternoon, just as I was leaving Dia:Beacon to catch the train back to New York City, I became aware of a faint continuous sound emanating from somewhere inside the Dia complex. The droning sound was lurking quietly in the background. Its location or cause was hard to pin down. While the drone had some musical characteristics, it did not resemble the sound of any musical instrument or sound-making device I was familiar with. It was gradually becoming louder, and appeared to follow me as I walked around. I couldn’t tell whether the sound was from a single distant loud source, or from many sources close by. I didn’t want to miss my train, so I left the building to make my way to the station. As I walked outside the building and through the landscaped gardens I could still hear it, now apparently leaking out from the building. As I walked further away, the sound appeared to become even louder. It was as though the whole building was emanating sound. I walked from the grounds, out of sight of the building, and could still hear the sound. Then the sound suddenly stopped, creating a gap in my experiencing of the world round me. There was a sense that something was missing. As I listened and looked at the world, it was as though it was being revealed to me for the first time.

Max Neuhaus’s Time Piece Beacon occurs seven minutes before each hour, when a drone, designed to blend in with its surroundings, is gradually introduced throughout the Dia:Beacon complex and surrounding gardens. The idea is that as the sound imperceptibly increases in volume it remains unnoticed by the public, until, after a few minutes, the sound abruptly ceases. Visitors, who have become accustomed to the sound without actually consciously noticing it, experience its sudden absence and instantly become aware of the foregrounded ambience that remains. It is therefore the silencing of the sound that activates the visitor.

One factor that links these three works is their framing of apparent ‘emptiness’. Philosopher Henri Bergson argues that gaps in our experiencing concern us as they impede our knowledge of our surrounding world and its potential threats. We, and all animals, have developed brains that exploit this centre of indetermination. The brain occupies this gap as our thinking empowers us to make nuanced responses in order to act and adapt to new circumstances that will guarantee our survival. When encountering these three artworks at Dia:Beacon, the lack of translatable content within my framing of each artwork created such gaps in my experiencing. In order to maintain experiential continuity I searched elsewhere for content, looking and listening beyond the ‘empty’ surfaces of the artworks.1 In my encounter with 6 Gray Mirrors, after looking at and into the reflections in the mirrors, which I contemplated as virtual spaces, my attention turned to ambient sounds that were entering Richter’s room from spaces elsewhere in the Beacon building. In Ryman’s Installation at Dia Beacon, painting forms were perceived as empty. Individual ‘blank’ paintings loitered in groups and became threatening, as they appeared to stare back at me. I imagined hidden depths behind their voided surfaces and a feeling that the whiteness of the exhibition had turned into a persistent sonic noise.

Both Ryman’s and Richter’s deployment of minimal content has the effect of foregrounding the framings themselves, rather than what is framed. In the case of Richter’s installation the mounted forms, each orientated slightly differently, were clearly alluding to an art exhibition. However, as there was no obvious difference between the forms themselves, there was little to be gained by viewing each one independently. Even in their capacity as mirrors, I could only make out dim gray reflections. Collectively, the mirrors were like membranes through which I felt the artwork was sensing and surveiling its own space.

Richter says, of his gray mirrors: “I’m trying to bring together the most disparate and mutually contradictory elements, alive and viable, in the greatest possible freedom. No paradises" (in Buchloh 2009, p.34). Thus, Richter’s “freedom” avoids any transcendent trajectory or outcome. This denial of outcome consigned my encounter to a kind of perceptual limbo. It was as though all three artists weren’t so much interested in content, but rather wanted make me aware of my own act of experiencing.

Bergson’s Space/Duration Composite

Bergson, in Time and Free Will, suggests we perceive experiences as a composite, where the two essential components of experience: duration and space, are blended, so that we don’t really notice them as separate components (Bergson 1913). Within this composite, Bergson argues, duration, which is qualitative, and space, which is quantitative, can be confused, whereby we tend to treat duration (in which we have time to feel a succession of differences in kind) in terms of space (which can only be measured). Bergson suggests that the advent of clock-based time is one example of this, where the minutes and seconds are seen to pass as arbitrary yet standardised movements in space on the clock dial. Thus, the clock dial quantifies, spatially, our qualitative sensing of pure duration.

Perhaps then, my self-conscious feelings that the artworks were surveilling me— together with my brain’s search for meaningful content that took me beyond the artwork frames into imagined voids and virtual spaces—was my imaginative masking of my endurance of the artworks’ empty screens and their lack of content. My time spent within the artwork experience was sensed qualitatively but misrecognised quantitatively via spatial imaginings of depths, voids, and virtualities. (Here, the term ‘virtual’ is not referring to cyberspace but to an imaginary, speculative space or place that exists in effect or essence, if not in fact or actuality). Differences in kind experienced through duration became confused within the experiential composite and were translated spatially as imagined extensities (hidden spaces) within the artworks’ site.

Bergson’s theory may also be applied to our understandings of sound within experience. Sound lives within a duration and frames duration with its material presence. Several sounds when occurring concurrently score duration’s inherent plurality. Most sound that I experienced at Dia:Beacon was via acousmatic listening, where I felt the effect of a sound without necessarily knowing its source or cause. Brian Kane in his book Sound unseen: acousmatic sound in theory and practice (Kane, 2014, p. 147) refers to a sound’s “acousmaticity” in which a sound’s source or cause is “underdetermined”. This opens up a gap between a sound’s effect and its source or cause can be unsettling, especially in relation to the spatial and visual world that we are simultaneously perceiving. This can lead to experiential antinomies, where what we see and what we hear don’t necessarily correlate. There is a human desire to close this antinomic gap by searching for possible sources and causes. Kane suggests:

The security at work in territorial listening depends on the rapid reduction of a sonic effect to its potentially predatory source, but acousmatic underdetermination forecloses the easy attainment of such security. There are always degrees of acousmaticity. (Kane, 2014, p. 149)

Kane appears to echo Bergson’s theory of a space/duration composite when he points out that we sometimes draw on our imagination to invent a sound’s source or causes when it is not visually apparent to us. One historical example Kane provides is of the ways in which the noises that accompanied natural events, like earth tremors, “often embellished natural events with ominous forces and supernatural causes.” (Kane, 2014, p. 4).

In Sound Unseen, Kane refers to Michel Chion’s theory of the cinematic acousmetre, which is sometimes employed in films, and which exploits the anxiety arising from the gap of understanding that ensues through acoustic underdetermination. The acousmetre is a sound, often a voice, that “floats or drapes itself around the on-screen characters” (Kane, 2014, p. 149). According to Chion the acousmetre has three powers and one gift:

First, the acousmetre has the power of seeing all; second, the power of omniscience; and third, the omnipotence to act on the situation. Let us add that in many cases there is also a gift of ubiquity—the acousmetre seems to be able to be anywhere … (Chion, 1994, p. 129-130)

I suggest that the acousmatic nature of certain sounds that leaked into the Richter and Ryman artwork frames—in particular, the sound of Max Neuhaus’s drone, which can be heard within Richter’s artwork—operated as a kind of acousmetre. However, these ideas don’t quite explain my experiences at Dia:Beacon. For while I felt surveilled within these artworks and sensed affect, I don’t think these feelings can be explained away by referring to lurking phantoms and the acousmetre.

A Temple of Sonic Haecceities

The three Dia:Beacon artists create antinomic experiences through their use of objects that are simultaneously painting-like and mirror-like, also through experiences where temporal and spatial realms do not correlate, and where the actual competes with the virtual for attention. These complex artwork framings are nested within the larger frame of Dia:Beacon itself. Dia:Beacon opened in 2003 and is housed in a large single story building that was formerly a box-making and printing factory for Nabisco. Its floor and basement area, covering almost thirty thousand square meters, has been transformed into showrooms for artists. Landscaped gardens surround the building (In the West Garden we can experience Louise Lawler’s Bird Calls (1972), a soundscape of bird sounds derived from the names of famous contemporary male artists). Artist Robert Irwin, together with architecture firm OpenOffice, is credited with the overall design. According to Dia’s former director Michael Govan, who oversaw Dia:Beacon’s construction, “Irwin helped Dia consider the design of the Beacon project in experiential and environmental terms as a totality” (Govan, 2015). In another discussion Govan suggests that “the result was intended as a series of immersive experiences of individual artists installations surrounded by Irwin’s mediating exterior” (Cook & Govan, 2003, p. 39). The idea was “to not control the path of the visitor but to provide tools and clues to keep them oriented” (2003, p. 38). As a “totality” Dia:Beacon demonstrates that it is also an installation with similar intensions to the installation artworks contained within. For, as Claire Bishop (2005, p. 6) reminds us, “in a work of installation art, space and the ensemble of elements within it, are regarded in their entirety as a singular entity”.

Dia:Beacon’s architectural spaces and the artworks they contain appear to activate each other as the Dia:Beacon site engages with what Miwon Kwon (2002, p. 13) describes as Minimalism’s challenge to the “hermeticism of the autonomous art object” and subsequent deflection of an artwork’s meaning to its space of presentation. Here the site perhaps goes a step further in neutralising what Kwon calls the “idealist hermeticism of the space of presentation itself” (2002, p. 13).This neutralization is apparent in the use of open-plan design and by a reliance on sunlight, which enters all gallery spaces via factory skylights plus new large windows retro-fitted to the existing perimeter walls. Rooms and objects are bathed in sunlight from a realm beyond the artwork’s frame. Dia, in fact, is a Greek word meaning ‘through’ or ‘conduit’ (Merriam-Webster dictionary).

Dia:Beacon is a quiet space, exhibiting stillness. Its visual and sonic ambience reminded me of being in a church or a museum. Its long galleries serve as ambulatories that enable temporal, processional contemplations of large minimalist artworks, often spread out across the floor, by artists such as Dan Flavin, Walter De Maria and Robert Irwin. This church-like ambience is no accident. Dia founders and original benefactors had ties to religion, some to Catholicism, others to Sufism, a form of Islam. Religious artworks were purchased and commissioned by Dia benefactors (the Rothko Chapel paintings, for example). In 1980, the Dia founders opened a Sufi mosque in a Chelsea building, originally intended as an art gallery, complete with Dan Flavin light works. Dia’s idea was to use art to provide a kind of religious experience, to transform the world. These connections can be explored further in Bob Colacello’s Vanity Fair essay, Remains of the Dia (1996).

Many artworks at Dia:Beacon have their own dedicated, chapel-like rooms that separate them from other works and the world-at-large. This includes the Richter and the Ryman installations. Cultural theorist Claire Colebrook writes:

A picture in a gallery or even a stained glass image in a cathedral may well have been isolated from the world of functional action and knowledge so that art in general is expressed in distinction from the world of habit, connections and work. [T]he power of art [is] to stand alone, to be released from the human eye’s tendency to synthesize its experiences into a world of its own. (Colebrook, 2006, p. 65)

Often though, when visiting individual artist rooms within Dia:Beacon, I was aware of distant sounds whose reverberation sonically rendered the whole building’s voluminous form. As visitors congregated in various parts of the building, their noisy expressive presence was dynamic and sometimes chaotic. Instead of perceiving these sounds as individual quantified events, I sensed them collectively as a singular, heterogeneous susurrus. As this susurrus leaked into artwork spaces, through gaps and doorways, it denied the artwork its complete isolation. The susurrus reframed my experience of the artworks as it introduced the sonorities of a lurking world into the artwork’s frame.

Not everyone noticed the susurrus, but it was present in all the Dia artwork spaces. I wasn’t always listening to these sounds; they didn’t preoccupy me. If anything, I sensed them as a quality, which is to say, I heard them, but as they were judged as non-threatening, I did not consciously listen to them. They did not attract my conscious attention as quantifiable events. However, they were nonetheless sensed as part of my artwork encounter, and contributed to a particular kind of durational framing; a ‘becoming’ that implicated the temporal flux of a surrounding evolving world. These framings can be called haecceities. In A Thousand Plateaus under the heading “Memories of a Haecceity”, Deleuze and Guattari explain:

They are haecceities in the sense that they consist entirely of relations of movement and rest between molecules or particles, capacities to affect and be affected. […] not defined by the form that determines it nor as a determinate substance or subject nor by the organs it possesses or the functions it fulfills. […] Tales must contain haecceities that are not simply emplacements, but concrete individuations that have a status of their own and direct the metamorphosis of things and subjects. (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987, p. 304)

Within Dia:Beacon some of these haecceity “individuations” had a sonic component that was literally “molecular”. For example, sound comprises air that is excited into pressure waves of “movement and rest” that I sensed with my eardrums. Deleuze and Guattari suggest that haecceities are not things in themselves; rather they result from a “metamorphosis of things and subjects”. Deleuze and Guattari (1987, p. 304) suggest that a haecceity, as an individuating composition, possesses “a perfect independence lacking nothing, even though this individuality is different from that of a thing or a subject”. Haecceities are non-personal: “a season, rainfall, wind, an hour, air polluted by noxious particles” (1988, p. 304). Perhaps, to this, I can add the sound of a refrigerator motor as it softly permeates the house.

I suggest that an engagement with any artwork, if framed durationally, can be considered as a haecceity that has “capacities to affect and be affected” (Deleuze & Guattari 1987, p. 304). As Deleuze and Guattari suggest, temporal and spatial encounters with haecceities take place through sensing “concrete individuations that have a status of their own and direct the metamorphosis of things and subjects” (1987, p. 304). At Dia:Beacon, these “things” and “subjects” are the artwork components and the building itself. I suggest that the susurrus that leaks into the artwork, whether quantitatively listened to, or sensed as a quality, became an important component of Dia:Beacon’s haecceities. These sounds, as I have described, include the collective noises of human gatherings, but also, the periodical noises of Dia:Beacon’s air-conditioning systems that individually turn on and off throughout the day, or the sounds from distant artworks that leak into the frames of an artwork.

These sounds possess ‘acousmaticity’, where their identity is underdetermined. Thus, they can sometimes be sensed as panoptic, omniscient, and omnipotent, like an acousmetre. One artwork that demonstrates these qualities is Neuhaus’s Time Piece Beacon, both when Neuhaus’s sonic drone is listened to, or when its quality is felt as it leaks into other artist’s rooms. It was in this sense that my experience of Neuhaus’s artwork, and even the sounds of air-conditioning, sometimes combined with artwork components to form haecceities. The only difference between Neuhaus’s sonic drone and air-conditioning is their respective qualities and intensities of air movement. Thus, haecceities, while often quite subtle, can contribute provocative and ambiguous qualities and affects to an artwork experience.

I suggest that haecceities, especially those that included a sonic component, actively reframed my experiences at Dia:Beacon, as their added underdetermined acousmatic sounds imparted qualities and implicated invisible territories outside the artwork’s frame. It can therefore be argued that it wasn’t each artist’s space that registered as a whole unit of experience, but rather, Dia:Beacon itself, which behaved in its entirety like an installation artwork, just as its designer, artist Robert Irwin had intended.

The question then, is how did antinomic experiences that resulted from the breaking down of Bergson’s space/duration composite, and which were delivered through a sound’s acousmaticity, the acousmetre and the haecceity, impact on my experience of each of the three artworks? How did each of the three works embody one or more of these concepts?

Neither/Nor/Is - Richter’s 6 Gray Mirrors

While enduring Richter’s artwork and its reduced content, my attention (or rather, my brain’s search for content) shifted from the virtual spaces reflected in the gray mirrors to the virtuality of Dia:Beacon’s sonic ambience that entered Richter’s space via its two large entrances. Within Richter’s room, hard surfaces focused and resonated this susurration. Thus Richter’s room reverberated its own spatiality, and within this focused ambience I could also discern the susurrus marking the larger institutional expanses of Dia:Beacon that were unfolding beyond the artwork. The soundscap subtly scored two worlds, where one spatial/durational composite was enfolded within the other.

This antinomic perception sonically replicated (and literally echoed) the functioning of Richter’s six monumental mirror/painting forms, whose visual reflections created virtual spatial images situated beyond Richter’s actual room, whereby the room had two extensities: an actual one and a virtual one. Thus, in my experience of Richter’s work, my perceptions provided overlapping composites of duration and space, rendered in different experiential modalities: one in the visual realm and one within the sonic. This sensory (and conceptual) disjunction is precisely what made Richter’s artwork so engaging for me.

Additionally, the sonic event caused by the stone caught in my shoe scored the complex susurrus persisting in Richter’s room. When the stone hit the metal skirting board of Richter’s room, in an instant the room’s extensity lived within the sound’s duration, framed in a beholding moment until the intense, short reverberation faded. The unexpected sound, heard acousmatically, interrupted established auditory and visual framings—real and virtual—creating a perceptual confusion and an exciting temporal space of presentness and unknowability. The artwork’s prior staging of coherence and authority was destabilised as Bergson’s experiential composite of space and duration was further split into realms of antinomic uncertainty.

Richter describes his gray mirrors dialectically as “a cross between a monochrome painting and a mirror, a ‘Neither/Nor’ – which is what I like about it” (Elger, Obrist, & Richter 2009, p.272). The stone’s sonic outburst however was an event of undeniable certainty that was apparent to me in the present moment. I had no recourse to images in memory that might explain the event. The previously existing virtual worlds within the susurrus had now been replaced by a more urgent need to negotiate the threat of the sudden sound’s intense presence and the underdetermined acousmatic gap that had opened up. The stone event’s immediacy destabilised Richter’s balanced contemplative dialectic of “Neither/Nor”, to which I might now add the word “Is”: Neither/Nor/Is.

There are several antinomic positions in play here. As it was me who inadvertently released the stone, I was thus present both as the proxy agent of the event but also as the recipient of the event’s agency. The stone’s ‘sounding’ against the skirting board became an avatar of my own objecthood, as the stone’s impact on and subsequent reflection off the artwork’s surface sonified my own agency within the artwork. The materiality of the stone’s acousmatic sound (as well as the stone’s actual materiality) refuted the ephemerality of the post-object artwork encounter. The stone event revealed the coexistence of duration and space, and the coexistence of theatrical and beholding moments. All these registers were simultaneously available to me within my encounter of Richter’s artwork.

Becoming Noise - Ryman’s Installation at Dia Beacon

My lack of interest in the content of Ryman’s paintings during my ‘naïve’ walkthrough caused me to experience them as what Deleuze (1986, p. 109) calls ‘any-space-whatevers’, whereby I lost my grip on the coordinates of the paintings’ surfaces. Deleuze develops the term in Cinema 1: “Any-space-whatever is not an abstract universal, in all times, in all places. It is a perfectly singular space, which has merely lost its homogeneity, that is, the principle of its metric relations or the connection of its own parts, so that the linkages can be made in an infinite number of ways. It is a space of virtual conjunction, grasped as pure locus of the possible” (Deleuze, 1986, p. 109). The paintings, as any-space-whatevers appeared as anonymous screens, thresholds or sensing membranes, which I looked through, beyond or within. I imagined extensities of concealed presences, sensed surveillance and fabulated spatial voids. Thus, my endurance became spatial.

The whiteness of Ryman’s paintings, together with their reduced symbolic content persisted throughout my encounter, causing my awareness to shift from individual, quantified spatial framings to a single, spatial and durational framing that encompassed all his paintings and the white rooms that contained them: a haecceity. I remembered my experience of Ryman’s artwork, strangely, as a kind of noise.

Paul Hegarty (2007, p. 3) in his book Noise/Music: A History, suggests; “Noise is not an objective fact. It occurs in relation to perception–both direct (sensory) and according to presumptions made by the individual”. A determination of noise is thus highly subjective. The concept of noise is problematic, for to assign it a label causes noise to become a recognisable thing, and so it is no longer a noise. As Douglas Kahn (1999, p. 25) eloquently states; “Noise can be understood in one sense to be that constant grating sound generated by the movement between the abstract and empirical”. This process of ‘becoming noise’ activated the whole of Ryman’s artwork as a single any-space-whatever, whereby virtual noise replaced my initial sensing of the artwork’s emptiness and silence. I remembered (or imagined) this noise as a sensation where signaletic and symbolic information was absent. I could no longer perceive depth, nor could I sense external temporal flux. What remained was a pure form of sensation in which I only sensed my internal durational and spatial being. Thus, within my encounter of Ryman’s artwork were encounters of various ‘any-space-whatevers’: the individual paintings, the overall whiteness of Ryman’s rooms, and my qualitative sensing of ‘becoming noise’, which all became components of a haecceity.

But did my experience of ‘becoming noise’ manifest virtually or actually within this any-space-whatever? It is worth taking the time to answer this in two different ways. In 1968 an unnamed art critic in the magazine Time, spoke of how Ryman’s paintings made people “laugh outright” (1968, p. 70-77). Art critic Robert Storr has also commented that Ryman’s white paintings can be “a trap … for those made chatty by silence” (Storr 1986, p. 74). Both anecdotes are perhaps trivial, however, they do illustrate that Ryman’s paintings succeed in problematizing engagement and confusing ‘naïve’ visitors. In these two brief examples, the visitor’s vocal expressions are possibly attempts to mask the confusion of their encounter; where a painting’s frame, perceived as empty of content, has confused subject/object relations. The Ryman viewing experience was not passive and spatial as the visitor might expect; rather the paintings’ perceived lack of content caused the visitor to experience an active durational engagement, and whereby sensing an experiential void, they contribute their own expressive vocal content in order to ‘fill’ the void. Such utterances are effectively attempts to reterritorialise the perceived spatial and temporal lacunae. Could it also be that at Dia:Beacon, my own encounter of Ryman’s paintings’ whiteness, which left me searching for content, and the noise I seem to remember as being present, was my attempt to reterritorialise the durational experience of the any-space-whatevers of Ryman’s installation; not with chatter or laughter, but with a memory, a haecceity containing a virtual ‘becoming noise’? If so, then my experience of noise can be thought of as my translation of the emptiness of Ryman’s white paintings from a qualitative, durational experience into quantitative white noise.

The second answer to the question regarding whether the noise was a virtual or actual thing became apparent when I revisited Dia:Beacon in 2016. Encountering the Ryman rooms again and listening more intently this time, I became aware of the actual presence of noise. Indeed, there was actual ‘white noise’ that slowly increased in intensity as I walked through the spaces. On investigation, I discovered noise emanating from a large air-conditioning duct located just outside the southern entrance to Ryman’s spaces. What I had hitherto considered as a virtual ‘becoming noise’ was, in fact, an actual ‘becoming noise’. For the noise of air conditioning (which is actually occasionally quite intense in certain parts of Dia:Beacon) had been sensed qualitatively as a compositional element of an individuated haecceity. My Ryman experience thus included sonic and durational components that were situated outside the artwork’s physical framing, and which had become components of a haecceity that composed and persisted within the artwork experience.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Large air-conditioning vents outside the southern entrance to Ryman’s exhibition spaces. Photo: David Chesworth.

Before, During, After - Neuhaus’s Durations

Max Neuhaus’s Time Piece Beacon is heard just before each hour and is experienced throughout the Dia:Beacon complex and gardens. The work is remarkable in how it caused me to negotiate spatial and durational framing. Christoph Cox, writing about Time Piece Beacon draws on Michael Fried’s critique of minimalist art, in which Fried accuses Minimalist artworks of having a theatrical and durational presence within the space of the encounter (Cox 2009). Cox also makes interesting comparisons between Max Neuhaus’s and John Cage’s compositional methodologies, by discussing how Cage’s 4’33” also problematises Bergson’s durational spatial composite, including the title, in which the duration of the work is quantified. Cox considers the Neuhaus artwork a prime example of the type of installation artworks starting to emerge in the 1960s and 1970s that transition beyond a reliance on the art object, and that these works instead emphasise ephemeral occurrences within duration and space, artists like Dan Graham, Robert Morris and Bruce Nauman, for example, and conceptualist artists like Joseph Kosuth and Lawrence Weiner. This is also apparent in Richter’s experiments with framings of glass and mirrors begun in the 1960’s, which culminated in his Gray Mirror artworks. For Cox, this ephemerality is particularly apparent in Time Piece Beacon, where, “[the] temporality and ephemerality of sound allow it to bypass objecthood and the instantaneity of opticality” (2009, p. 122). Time Piece Beacon primarily engages not with objects and our gaze, but with our sense of lived time and duration.

Memory is crucial to our experience of duration, for we are aware of duration’s persistence as it passes from our present into our past. However, in Time Piece Beacon I found that my memory could not be relied on, and this was disconcerting. In my experience I never actually heard Neuhaus’s introduced drone begin, rather, the sound became apparent to me at some point as it became louder and registered on my conscious sense of hearing. I suggest that prior to consciously listening to it, the sonic drone, as a seemingly innocuous compositional element, was, in fact, being sensed as an affecting quality. Even as the sonic drone became louder I didn’t necessarily perceive it as a discrete thing. That the sound was present to me, even if I was not consciously aware of it, only became evident when it suddenly ceased and I noticed its absence. Or rather, I noticed the absence of something, and I could not say what this was. Only retrospectively was I aware of the sound’s existence, although I had previously felt its affecting force within a haecceity. Thus, I was left with a memory of something through a perception of its absence, not its presence.

With the sudden removal of Neuhaus’s introduced drone, I had a new sensation individuated within a new haecceity. A durational void emerged as Bergson’s experiential composite broke down into its component parts of duration and space. The spatial realm suddenly provided me with a confusing quantitative expression of the qualitative sonic void. As well, I was left with a memory of the previous haecceity (when the sonic drone was sounding).

Thus, in Time Piece Beacon duration was experienced in two ways: Firstly, where I retrospectively contemplated one haecceity that had passed in relation to another that remained; and secondly, once Neuhaus’s continuous sound ended, I lost my sensing of the continuum provided by the drone and, perhaps for the first time, became aware instead of my immediate spatial surroundings and relations to the unfolding flux of durations articulated through different sounds (outdoors at Dia:Beacon this included sounds of unseen cars, birds, voices, insects, wind, and train horns).

When Neuhaus’s introduced sound ceased, I became troubled by the removal of a sonic element that was subconsciously contributing to my territorialisation of the surrounding milieu. The perceived sonic void that followed the drone’s removal suddenly deterritorialised and foregrounded heterogeneous sonic unfoldings in the surrounding environment, and I was also left anticipating some future change that might explain my present and past experience, and perhaps provide closure to my current and on-going temporal frame. Within this encounter, different perceptions dialectically oscillated between different kinds of audition: qualitative hearing/quantitative listening, presence/absence, knowable sound/acousmatic sound. It also called on different ontological framings: space/duration, musical sound/non-musical sound. These oscillations contributed to an awareness of having experienced two separate and different haecceities.

The two temporal haecceities that occur within Time Piece Beacon caused antinomic experiences of past, present and future. In doing so, the artwork was able to frame pre and post-cognitive moments of sensation. As there was a pre-cognitive sensation that was not consciously sensed by me, I had a memory of having a sensation but I could not access what that sensation was.

While Neuhaus’s drones are certainly minimalist, their status as music is contestable. Neuhaus’s makes choices of sound qualities in his drones (which he says he carefully composes) that seem to question its own ontological status. For, in Time Piece Beacon, his introduced sound exists as and within a perceptive threshold, where it is barely audible as an event in itself. The sound starts so quietly that it could be argued that there is no beginning but rather the sound is noticed as already present and already territorialised within the surrounding sonic environment. The sound therefore doesn’t present as a foregrounded, deterritorialising event, which might be case if the sound were perceived as musical. However, when I listen to his drones carefully, I notice that they contain rich interior harmonic unfoldings that are undeniably musical. This is apparent both in his Dia:Beacon artwork and also in his New York-based installation artwork Times Square. His drones therefore have an ambiguous quality that exists on the boundary between a sound’s territorialising capabilities and music’s deterritorialising effects.

Concluding Remarks

The staging of antinomies is a core experience of these three artworks. This occurs through each of the artists’ strategic deployments of forms and forces that initiate paradoxical perceptions and meanings through dialectic that never synthesises. Within the spatial/durational composite articulated by Bergson I confused durational experience with spatial experience. Within Chion’s audiovisual complex I listened (and sensed) acousmatically. Both durational and spatial confusion and acousmatic listening resulted in the fabulation of surveilling extensities.

While acousmatic listening and its relation to frame is deliberately exploited in cinema, at Dia:Beacon it occurs inadvertently by listening to sounds leaking in and out of framed sites. Listening acousmatically to sounds entering the artwork frames from outside problematised my framing of the artworks. This is because acousmatic listening enacts relations between the framing of the artwork and a world existing outside the frame. The outside world, through the sonic realm, becomes implicated in the artwork experience.

Ultimately, these artworks demonstrate that we are constantly constructing the world around us as we reconcile different perceptions, thoughts and actions. These processes are complex and tenuous, and can easily become challenged and undermined by antinomic framings of experience. What my research has shown is that in my experience of these three artworks many antinomic framings occurred through the temporality of my encounters and through the sonic materialities that became part of a durational framing of these artworks.

Haecceities compose with things—objects or subjects—but are not those things; rather they contribute subtle, affecting framings of experience. Haecceities created moods that contained and directed affects and forces. These haecceities were (and persist) in the virtual, as memories of what occurred, and it is in this way that they most successfully frame duration: as individuated memories of sensed durational experience.

Speculative Realist philosophy posits an approach to analysing experience that favours respect for the agency of objects within the world and their shifting qualities, as an alternative to experiences of objects described through their direct consequence for human subjective and objective relations. For speculative realist philosopher Quentin Meillassoux, (2008), human subjectivity is a symptom of what he calls correlationism. His term describes a propensity for the world in all its facets and complexities, to be seen, described and so ‘known’ solely through human perception and interaction. We know things via our perceptions and subsequent reasoning. The Richter, Ryman and Neuhaus artworks play out through this correlational circle, where, as a visitor, objects and ephemeral experiences that Michael Fried derides as “objecthood” were oriented towards me, or, in the emptiness of the frames I imagined what was deliberately withheld.2

This desire to rediscover and project objects (and indeed objecthood) is possibly a strategy that is imbued within the minimalist roots of these Dia artworks. They are, for the most part, post-object works, where the ephemeral has replaced the object. As I experienced at Dia:Beacon, the sound object, once it is injected with agency, can quickly undermine the ephemeral. This can happen via the materiality of sounds leaking into frame from ‘elsewheres’, and also, as in my experience at Dia:Beacon, by an object-on-object encounter, such as the ‘stone in shoe event’.

The small stone caught in my shoe gets accidently flicked against the gallery wall making a sudden sound that scores the artwork’s surface. The source and cause of this object-on-object event is the stone and the artwork acting on each other. That I happened to experience it as a sonic event is inconsequential to the action itself. Many sounds we experience have a non-human causality (such as the sound of wind, heard as moving air acts upon the leaves of a tree, and ocean waves), but where the sound of wind and ocean is imbued with meaningful affect for humans, the sound of the small stone hitting a metal surface withheld both ontological and ontic meaning from me. What the ‘stone in shoe event’ did do, however, was to emphatically introduce the materiality of the unknowable acousmatic object into the ephemeral artwork encounter.

Neuhaus’s Time Piece Beacon possibly goes further in revealing a non-correlationist realm of ‘experience', for when his introduced drone abruptly ends, I am left with a memory of 'something' that existed only through my perception of its absence. Only retrospectively then, am I aware of the existence of the artwork, not as an artwork framed from the world, but as a component of the world experienced as a haecceity. As such, Neuhaus’s drone is potentially an un-correlated sound that exists in the virtual without ever being accessed as an actual thing. Thus, in experiencing Time Piece Beacon, I felt the sense of loss of something that I never was able to subjectify or objectify. In doing so, Max Neuhaus’s ‘silent alarm clock’ provides a wake-up call; alerting us to processes, existences and trajectories that by-pass human subjectivity and objectivity.

- 1. This search for content can also be evidenced in visitor behaviour within Richter’s space. Often, when visitors sat to rest on the bench provided for contemplation, they pulled out and gazed at their mobile phones.

- 2. Fried’s term “objecthood” refers to the “situation” of experiencing a minimalist (or Literalist) artwork that he argues, has shifted from belonging to he “beholder” who contemplates the object internally, to the theatrical encounter with the artwork itself in space and duration and via its ephemeral “objecthood”. See FRIED, M. 1998. Art and Objecthood - Essays and Reviews, University of Chicago Press.