Noise in the tropical underground

In the city of Yogyakarta, in the centre of the island of Java lies the Sultan's palace and the city’s art museum, Sonobudoyo, placed almost opposite one another. Between them there is a large square, Alun-alun Utara, with 63 trees – one for each year of life of the prophet Muhammed – and in the corner a large statue of General Sudirman, who, despite his apparent weakness, still lead a guerilla campaign against the Dutch in the war of independence at the end of the 1940s. In the middle of the square are two banyan-fig trees enclosed by a white fence. It is said that if one walks between these two trees blindfolded, it brings great happiness.

In this way, the square at once bares the marks of religion and mysticism, of art and culture, of the ruling sultanate, of the military's heroic image, and of Indonesian postcoloniality and independence. All these components are important to the identity of Yogyakarta and are what constitutes its complex society. In addition to its representation through the trees in the square, Islam makes its presence felt with the characteristic and ubiquitous calls to prayer and with many of the women, but far from everyone, wearing headscarves. Islam is a natural part of everyday life and culture. Here, there are also extremist groups led by 'gangsters' who respond with violence to blasphemous expressions and actions. Experimental music and noise, as such, however, seem to be left in peace.

The majority of the city’s inhabitants are followers of kejawen – a mystic tradition that blends faith in the Almighty Allah and an everyday relationship with the ghosts ancestors and many other kinds of spirits. And in the midst of this paradoxical place, just south of the equator, there is also something that you might not readily expect to find here, a vibrant underground scene of noise and experimental music. In fact, it is one of the main centres for this type of music in Southeast Asia.

In many ways, Yogyakarta is similar to the rest of Java, but it also has a special status. This is because, firstly, the region of Yogyakarta, which shares the same name as the city, is the only one in Indonesia to receive cultural support directly from the government. Secondly, this region is also the only place in Indonesia, where the sultan and the governor are one and the same person.

The reign of the sultanate began in the 18th century, when the previous Hindu-Buddhist kingdom split in two and to this day the sultan is both an Islamic leader and a cosmological figure. The current sultan, the tenth in the series and nicknamed Hamengkubuwono – the protector of the universe – is said, like his forefathers, to be married to the same spiritual queen, Ratu Laut Selatan, the goddess of the sea, to whom the sultan, once yearly, sacrifices his clothes. It is said that, in retribution for his abstinence from his spirituelle marriage, he has had no sons and, in place of his five daughters, his younger brother shall inherit the throne. Recently, this situation has led to the sultan working to change the law of succession in favor of more gender equality, so that the eldest of the daughters can inherit the throne.

The Sultan's Palace with pictures of the Sultan himself and his family. © Sanne Krogh GrothYogyakarta is also a university city and therefore has drawn a great many highly educated newcomers to it. "People from the outside are having a hard time with this form of government," says Indra Menus, one of the initiators of the local festival Jogja Noise Bombing, organized by an artist collective of the same name. "But if you were born in Jogja, it’s what you prefer." It is not only the political regime over which Javanese mythology exercises great deal of influence. Several of the artists I met seem to find inspiration in Java’s traditional art forms, such as Wayang (puppet theater) and Gamelan (musical ensemble), as well as in the traditional central Javanese religion and life practice, Kejawen.

The Sultan's Palace with pictures of the Sultan himself and his family. © Sanne Krogh GrothYogyakarta is also a university city and therefore has drawn a great many highly educated newcomers to it. "People from the outside are having a hard time with this form of government," says Indra Menus, one of the initiators of the local festival Jogja Noise Bombing, organized by an artist collective of the same name. "But if you were born in Jogja, it’s what you prefer." It is not only the political regime over which Javanese mythology exercises great deal of influence. Several of the artists I met seem to find inspiration in Java’s traditional art forms, such as Wayang (puppet theater) and Gamelan (musical ensemble), as well as in the traditional central Javanese religion and life practice, Kejawen.

Experimental music and D(o) I(t) Y(ourself)

The spiritual influence became clear in the first of the concerts I attended. I had first heard about this concert during my meeting with the Jogja Noise Bombing Collective, who I met at their hang-out – a local coffee shop – on one of the first nights I spent in Yogyakarta. Their festival was, actually, the main destination for the trip.

The concert took place at the Garasi Performance Institute, led by the multidisciplinary performance group Theater Garasi. I did not know what to expect when looking for the venue, which was in the southern part of the city, from the taxi in the dark and the rain. It was also an unknown venue for the driver. After some discussion, I convinced him that he did not have to wait for me and I ran into the torrential tropical rain.

Inside, I was first met by a highly engaged group of organizers and an audience of about 50-60 people. Through some brief conversations, it became fairly clear to me that the audience was predominantly artists and musicians, art and music students or people who worked in galleries or similar fields. Here, there were only one or two bule – slang for people from the West, which literally means 'albino', but the vast majority were Indonesians.

Once the hammering of the rain against the tin roof of the venue stopped, the concert began. The evening's program consisted of just under two hours of experimental and investigative music, performed by an ad hoc ensemble of five musicians and a vocalist. It was performed with instruments that may very well have been made of 'nothing' but, in the context of this concert, they added a great deal to auditory and visual expression.

Teater Garasi: Lintang Radittya, Jangkung PP and Mo'ong. © Sanne Krogh Groth

Teater Garasi: Lintang Radittya, Jangkung PP and Mo'ong. © Sanne Krogh Groth

The most noteworthy characteristic of the concert was this variety of self-built instruments. There was a colorful flute and double bass made of garbage (Mo'ong); There were DIY synthesizers – mounted on a modern Wayang puppet made of plexiglass – and a theremin (Lintang Radittya); There were different kinds of keyboards (Yennu Ariendra and Andryanade) and old Gamelan percussion, which seemed to have been specially prepared for the occasion (Jangkung PP). The ensemble performed primarily on the floor in a semicircle with the smoke from incense sticks shrouding the stage, as if they were a traditional Gamelan ensemble. The music was improvisational and divided into pieces. Not everybody played in every piece. Some things had been planned out in advance but, by their own account, it was not much.

The interplay between the musicians and the space nevertheless proved to be incredibly well-balanced and dynamic, resulting in a concert with an organic feel, in which quiet and meditative passages gave way to walls of noise. This, in conjunction with the hard resonant surfaces of the rooms materials, led to the gradual build up of reverberations and beats. Also, the professional lighting gave the concert an almost magical glow. The French performance artist, Cecile Bellat's, reading provided a great addition to the abstract soundscape, which it broke into discrete words that were at once more tangible but that still remained abstracted by virtue of the French language. A single musician, Mo'ong, did not sit on the stage like the others, but played the larger instruments standing and thus attracted more attention.

After the concert, I spoke with Mo'ong, who introduced himself as a composer, about his own and traditional Javanese musical practices. That he had introduced himself to me as a composer was something he immediately problematized by saying that the term was one he had acquired from his education in Western European music history and composition at the conservatory. In Indonesian, there is no word for composer just as there are no words for music or instruments. Music and art are understood as everyday practices on an equal footing with other chores and are therefore considered to be more than just a pleasant diversion and not isolated from daily life. When playing, resources are available not instruments and the music produced is a joint creation, which does not have one individual composer. It is something that occurs in the situation.

Lintang Radittya, DIY synthesizer builder and musician, continued this line of thought, when we talked about noise a few days later. "To call a specific music noise is artificial. Noise is nothing in itself. It's running in our blood, it's a part of us. It is not an isolated phenomenon that can be separated from anything else. What is noise? Gamelan is, for example, also noise."

Teater Garasi: Lintang Radittya, Jangkung PP, Mo'ong and Yennu Ariendra. © Sanne Krogh Groth

Teater Garasi: Lintang Radittya, Jangkung PP, Mo'ong and Yennu Ariendra. © Sanne Krogh Groth

Noise, noise, noise

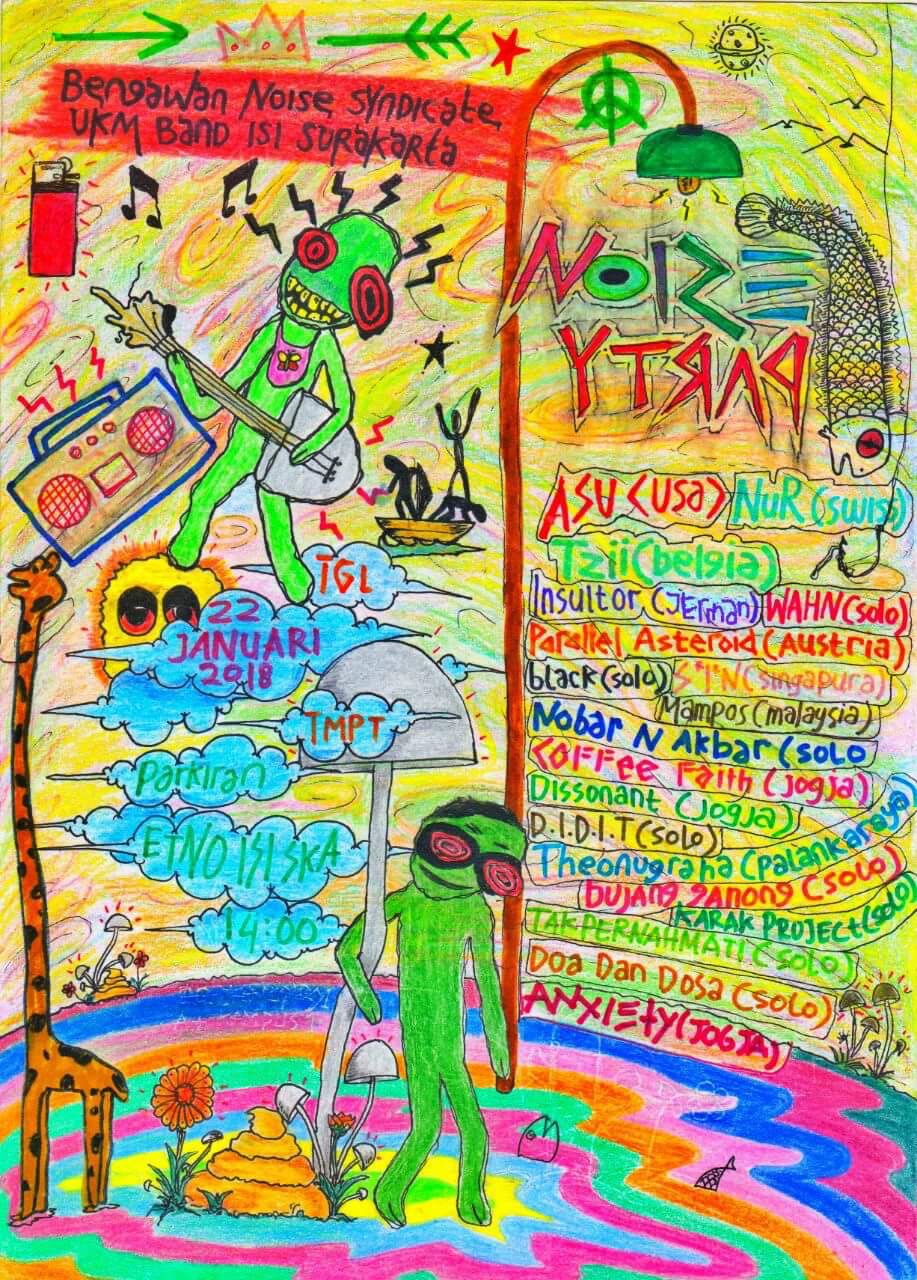

Noise, nevertheless, did manifest itself as a present and strong practice, or even genre, during my visit; over the two days of the Jogja Noise Bombing Festival 2018 and throughout the one day concert at the university, ISI (Art Institute of Surakarta), in the neighboring town of Solo, organized by the collective Bengawan Noise Syndicate.

The artists' collective Jogja Noise Bombing, who organize their eponymous festival, was formed in 2009. Just as the festival has grown over recent years, so too has interest in the Indonesian noise scene. In Cedrik Fermont and Dimitri della Faille's book, Not Your World Music from 2016, the authors describe the scene in Yogyakarta as South-East Asia's strongest. And, a little to the surprise of the members of the collective, there is currently at great deal of international interest in their work.

Indra Menus, who performs under the name To Die, is described in the book as "a noticeably active person in the noise scene, one of those who connects the dots between the local noise and experimental artists, and the punk scene" (p. 112). During one of our conversations, Indra Menus stated that he consider three primary reasons for this international attention: The band, Senyawa’s, major international success (including through Vincent Moon's film and most recently an interview in The Wire), the documentary Bising about noise and experimental music in Indonesia and, finally, the aforementioned book. He is also a diligent documentarian and is behind the two-piece documentary series Pekak!, consisting of a DVD of 123 experimental works from all over Indonesia (1995-2015), and a book that deals with the relationship between Japanese and Southeast Asian noise.

Indra Menus helped launch the collective, which, in addition to concerts, also worked to develop the concept of Jogja Noise Bombing-bombing as an equivalent to graffiti bombing but with sound. Basically, it's about riding a motorcycle with speakers and amplifiers strapped to the back. One finds a suitable place – like a busy street corner – and starts to play noise in the street. The motivation behind these pop-up events is not entirely clear. It could be a way to reclaim public spaces, like in the first of the group's bombings, where they found a traffic jam and played noise. The provocation might have been there, but, taking into account the noise of an Indonesian traffic junction filled with motorcycles, the noise from the speakers could not have offered a major contrast to the existing soundscape. The provocation may have actually been more readily experienced by staying on the street itself.

For the latest bombing it may have been that it was the 'setting' that was inviting. This took place in December 2017 in connection with an annual city party, during which a motorcycle dome was one of the main attractions. It was one of the members of the group, Hendra Adytiawan, who came up with the idea and suggested that they go there: All they had to do was ask for a power outlet, after which the dome could become the stage for a pop-up noise concert while the motorcycles drove around them.

Documentation from Jogja Noise Bombing 2017. © Hendra Adytiawan on Instagram

Documentation from Jogja Noise Bombing 2017. © Hendra Adytiawan on Instagram

Jogja Noise Bombing Festival

As the stretch of time between spontaneous bombings become longer, the Jogja Noise Bombing Festival, which appeared in 2013, has grown and has gradually been professionalized over the years. At the first festival, Indra Menus tells me, the only attendees were those who themselves going to play. In 2018, the number of participants was between 50-70. The PA and speaker systems were much better than they had been before. The same was true of the marketing, and there was a greater number of international guests. This year, for example, besides local performers, there were also invited artists from other cities on Java, Kalimantan and Bali. In addition, there were performances by artists from Malaysia, Singapore, the Philippines, Belgium, Switzerland, USA, Austria, France and Germany.

The festival took place over two evenings, January 19th and 20th, at the club, Barcode Kitchen and Bar. Every evening, the festival started after the evening call to prayer at around 18.30. On Saturday, the concerts continued until kl. 22 (after which the club took over), and on sunday until midnight. During this time, there were performances from the 30 names on the poster and some extras. In other words, I had attended a very packed program.

Group photo at the Jogja Noise Bombing Festival. © Sanne Krogh Groth

Group photo at the Jogja Noise Bombing Festival. © Sanne Krogh Groth

Curatorial marriages

The festival was organized so that almost all the participants (bands and soloists) were paired. Indra Manus decided who would play with who and let the musicians know who they were to play with on arrival. I asked the Belgian artist, Tzii, about the possibility of making backroom deals on how to prioritises the 20 minutes that were made available, to which he replied, "Well, I'd like to start a conversation first. But if the answer is 'harsh noise' from my fellow players, it's the end of the conversation. Then we play harsh noise."

And, for the vast majority of the Jogja Noise Bombing Festival participants, harsh noise it became. Several attendees told me they specifically turned up for the intensity and noise of this festival, but admittedly other elements could also be found when performing in different experimental, noise and electronic genres. This intense cultivation of explosive noise was deeply fascinating. Often, the performers were placed opposite each other at tables, where they battled against an another. During these battles they would play 40-50 second passages of noise, to which the opponent then responded in kind. The sounds came primarily from shakers with contact microphones afixed, which could also be screamed into. These sounds were driven through each musician's boards, which were comprised of gear such as analog synthesizers and guitar pedals. During the most intense passages, the audience stood close to the musicians and pushed into tables, each other and the musicians. Sometimes musicians were physically lifted if the audience thought the energy was disappearing. Everyone – musicians as well as audiences – participated in the noise and contributed to its constant acceleration.

This dynamic especially shone through in the performances of the Southeast Asian artists. The battle between Aditya Tri P. of Wahn from Solo and Indra Menus from the Jogja Noise Bombing collective was like a battle between local nestors, closely followed by Singapore's nestor SIN, who emerged as a mix between a coach and a referee in a boxing match.

Indra Menus and Aditya Tri P. of Wahn battling. © Sanne Krogh Groth

Indra Menus and Aditya Tri P. of Wahn battling. © Sanne Krogh Groth

The 'battle' between, Belgian, Tzii and Schizophrenic Wonderland from Singapore also reached ecstatic heights with crowd surfing and illustrating impressive endurance. The opening works both Saturday and Sunday were energetic too: the first night with Giga Destroyer from Yogyakarta and Jeritan from Samarinda on Borneo, who started things off with a surprisingly braggadocious, resounding vocal roar. The following day featured Malaysian Mampos, who offered really harsh noise, and the local musician, Coffee Faith, contributing with ambient sounds.

Not all of the pairings worked equally well, however. The American musician, VX Bliss, obviously had difficulty playing against the harsh noise trio Sarana from Samarinda (who performed as a duo). VX Bliss's attempts to hold on, which were clearly under great frustration, came to dominate what was expressed. I could not help but think whether there were some substantive cultural differences between these two kinds of noise? Is Southeast Asian noise somehow aesthetically different from elsewhere? In this meeting, it seemed like it. But in other constellations, the meeting of these approaches to noise resulted in a game built on mutual curiosity – on the home teams terms.

Two of the members of the trio Sarana from Samarinda, Borneo. © Sanne Krogh Groth

Two of the members of the trio Sarana from Samarinda, Borneo. © Sanne Krogh Groth

Others brought this contrast out quite clearly, such as the instrument builder Anggarayesta and the noise musician Nugraha Indra from Bandung on Vestjava, and the American musician, J3M5. The former duo initiated a set of drone-like electronically manipulated sounds produced by one of Anggarayesta's advanced instruments, after which J3M5 took over the sound with hard beats produced by his modular synthesizer to build up an ultra controlled ocean of noise. In a similar way, the Indonesian musician, Mad Dharma, who had roots in the stoner doom genre, began the set with heavy and slow guitar playing, after which the Filipino musician, Lush Death, contributed with high-frequency noise from the harsh noise spectrum. The set ended with the guitar re-entering, which gave the sound both a sense of gathering and a feeling of lifting.

Mad Dharma and Lush Death – stoner doom meets harsh noise. © Sanne Krogh Groth

Mad Dharma and Lush Death – stoner doom meets harsh noise. © Sanne Krogh Groth

Among the artists who performed were also those with a more conceptual expression, such as the duo ASU (USA), consisting of Gilang Damar Setiadi (Yogyakarta) and Sean Stellfox (USA / Yogyakarta). As their alter egos, these artists performed in masks and robes on drums and modular synthesizers, respectively. ASU (USA) has, according to their own description, an appropriately mythical origin: “[b]orn in the clouds of Venus, but residing on Earth. […] banished from their home planet for playing too loud. After one night of partying on the Mothership with Parliament-Funkadelic, Sun Ra, and Bowie, they decided to pay Earth a visit. Since then they have been spreading Venusian Noise to the citizens of Earth.”

There was also a visit from the duo Parallel Asteroid (Vietnamese sound artist, Cao Thanh Lan, and Austrian musician, Gregor Siedl), which was also largely conceptual, using samples of the sounds of biscuit being eaten and from live photography. They were the only participants who spoke to introduce their performances and gave instructions for it. The concert was concise and could have easily fit in a Western European experimental music or performance art festival. But in the Javanese context, it suddenly seemed to have arrived from a planet even further away than the one from which ASU (USA) had come.

Following this was a meditative and drone-like set by Garage Olimpo, played on traditional Indonesian instruments before the festival was brought to an end by the Swiss musician, NuR. Her solo set was quite controlled as she got her sampled farts to fill the room. Noise had returned to the space and the festival had come full circle and landed not too far from where it began.

Parallel Asteroid samples biscuit eating. © Sanne Krogh Groth

Parallel Asteroid samples biscuit eating. © Sanne Krogh Groth

Even though noise, and especially harsh noise, was central to the program, the range of sounds on display was incredibly diverse. Harsh noise had been obviously central to the curation, while several of the other genres seemed to play only a more peripheral role. The wide range required a little transition from concert to concert, which, as I said, ran in 20 minute intervals. This mix of genres affected the festival's flow, which ended up being a bit uneven. However, a major side benefit of this was that I became well acquainted, not only with Southeast Asian harsh noise artists, but also to many other types of noises and experimental music. One could say that the festival was, overall, "noisy" – which fit the genre and context quite well.

Togetherness in Solo

On Monday, the day after the festival, I traveled with six of the artists to the neighboring city of Solo and The Indonesian Institute of the Arts, Surakarta (a university and conservatory also known as ISI), where the local noise scene had organized a one-day festival on campus. With Rio Nurkholis Syaifuddin and Gilang Damar Setiadi on the train to Solo. © Sanne Krogh Groth

With Rio Nurkholis Syaifuddin and Gilang Damar Setiadi on the train to Solo. © Sanne Krogh Groth

"This is underground!", shouted the organizer, Betet, through the loudspeakers with a bottle of local sugar liquor in his hand, when the festival finally began after five hours of delay. Although we stood under canopies in the middle of the conservatory's campus with Gamelan orchestra rehearsals in the background, I was inclined to agree with him. And when, at the end, he apparently spontaneously drove a motorcycle onto the stage and intoxicated during one of the performances, I was convinced – this was underground.

The idea that the Jogja Noise Bombing Festival had become professionalized over the last five years now made sense, and the visit to Solo felt as if I had traveled a couple of years back in time to the roots of Javanese noise.

Musica Htet from Myanmar is a classical bassist, but has left the techniques of Western art music on the shelf. Instead, he had built a bass that can be disassemble and lives the life of a impro-noise musician. In Yogyakarta he had played a solo set, in which he performed a long bass improvisation along with live electronic manipulation of recorded soundscapes including chimes and bells which were, for me, reminiscent of his home region. In Solo, he also played improvised bass – and was spontaneously accompanied by the aforementioned motorcycle towards the end of the set.

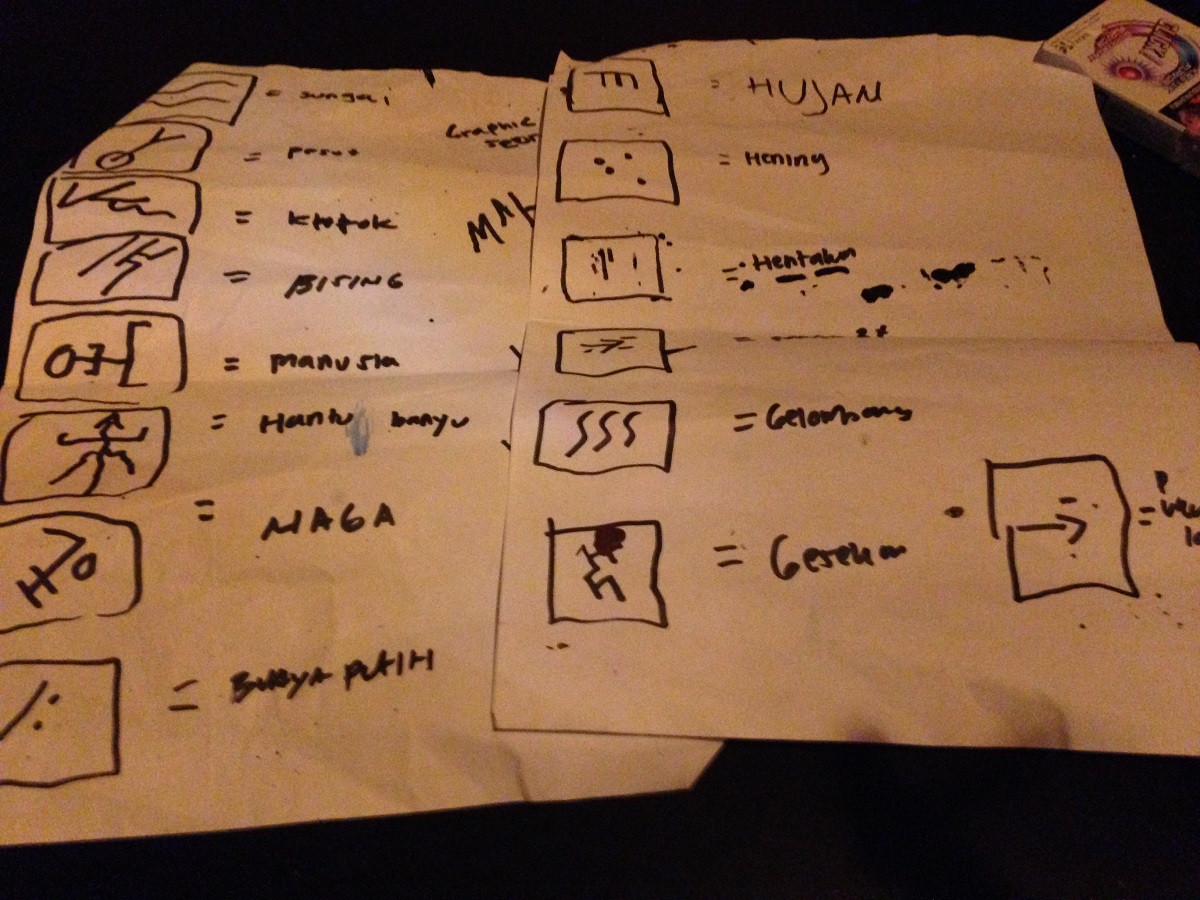

Theo Nugraha from Borneo based his performance on graphic scores based on traditional written language from Borneo. Previously, Nugraha had exhibited the scores in the context of an art gallery. In Solo he performed the scores on a hacked Nintendo together with the local performer, D.I.D.I.T., who, in contrast to the Nintendo's little melodic tunes, produced more uncontrolled noise with a long string with contact microphones attached. The scores were also hung up on this. Towards the end, when the scores gradually fell down and lay scattered on the floor, a local (and very drunk) vocalist from the audience joined the performance providing a spontaneous recitation and growling. Four to five other audience members did the same and contributed to the noise with a drum with metal in it.

Theo Nugraha from Borneo during the one-day festival in Solo. © Sanne Krogh Groth

Theo Nugraha from Borneo during the one-day festival in Solo. © Sanne Krogh Groth

Common to the approaches of Music Htet and Theo Nugraha's was their conceptually point of departure, both of which can be found Western European art music: Htet, with his self-made double bass with which he improvised, and Theo Nugraha with his graphic scores. What they also had in common was that they stuck to their own means of expression and concept, in spite of the spontaneous onset of improvised noise makers, which included whoever and whatever one could find nearby. This meant that the concerts did not end in pure inferenos but that there was still a strong intensity, a sense of inquiry and concentration present in the work.

But at the same time the concepts were challenged and pushed in a way that I had not experienced before. In this situation, noise was not only a musical genre or a particular sound quality, but became a phenomenon that disturbed all that appeared as ordered.

Graphic scores based on traditional written language from Borneo. © Sanne Krogh Groth

Graphic scores based on traditional written language from Borneo. © Sanne Krogh Groth

Epilogue: Noise as a situated social phenomenon

After the concerts in Solo, everyone met for a meal late at night at one of the local street kitchens. When we sat together on the final night in Solo, S.I.N. from Singapore asked what had made the greatest impression on me. Instantly, I replied that it was probably a strong sense of togetherness – not only between the musicians, but a togetherness that I also enjoyed during my ten days in Yogyakarta. This community feeling, I think, is unique to this place. Many of the musicians worked not only with music but also had interests in various forms of social work and activism in the pursuit of strengthening citizens' rights and living conditions. This practice is not only for art, but for life in general.

This distinctive feature was expressed in one of the other communities I visited, namely in the Lifepatch group. Lifepatch is a collective of engineers, scientists and artists with strong social motivation. Through DIY workshops, they teach people skills of which they are in need. For example, Timbil, a chemical engineer, told me about a 14-day workshop that he had arranged with among others, the media artist, curator, synth and instrument builder, organizer and so on, Andreas Siagian. During this time, together with the Hackteria.org network, they had invited the neighborhood to workshops that focused on biohacking. Each day, the participants could suggest what they wanted to work with, which eventually resulted in the completion of about 50 workshops on such diverse things as dildo building, alcohol distillation, and how to make their own tempeh from soybeans. The basic motivation is that people in Indonesia are in need of the knowledge of how to do thing – not only to understand and reflect, but simply to cope. There are so many thing to which there is just not access.

At home with Andreas Siagian, who demonstrates his home-made instruments. © Sanne Krogh Groth

At home with Andreas Siagian, who demonstrates his home-made instruments. © Sanne Krogh Groth

DIY synth building is part of this where Andreas Siagian has great experience. During a visit to his home, he showed me his DIY cassettes and his modular synth built from Indonesian components, which I heard in use during the last concert of the stay. His 'opponent' during this final concert was S.I.N., who also played on one of Siagian’s creations. The words exchanged after this last concert were as follows:

Siagian: – Argh … You won!

S.I.N.: – Yes, but you built it.

DIY, art in public spaces and socially oriented art projects are also high on the agenda of many Western European art scenes. So, it seems that there is perhaps not much new on this account But when it takes place in a context like that of Java, from my perspective coming from the western European avant-garde, the aspect of social orientation is pushed in a new direction. In Java, the social aspect, unlike some recent performances in our hemisphere, is not a fleeting visit to a social housing project. The social aspect is such an integrated element of the practice of artists on Java that it is so much more than a quick excursion out of the institution. The social community seems to be the institution in itself.

Such similarities and differences open new perspectives and possibilities for this art form, which I thought I knew so well. The challenge lies in meeting this new field that seems so much like our own. We must spot the similarities, but also embrace the difference in a way that neither alienates nor exoticizes.

Thanks to Emil Palme for pointing me in the direction of Yogyakarta, and thanks to Nils Bubandt for leading me there.

Translated by Macon Holt.