Sound as Shield

Abstract

The essay probes poetics and the politics of a life-affirming operation in which Ukrainians have been self-engaged to resist subjugation and assimilation under Russian colonialism. It leads through the scene of historical and idiosyncratic experiences to ask how speech and action create conditions for life to be where it has been pressed into non-being in the process of cultural genocide. Ukrainian inter-lingual Surzhyk-poised journey through forced russification is taken as a path to tracing the iterations of resisting life that crafts itself in the surzhykness of its affirmative gestures. I write to reassess the poetics of relation between the oppressor and the oppressed toward expressions of fugitivity and fabulation, and a posture of being in a mode of self-defense that keeps one from perishing. It is my argument that Ukrainian protocol for collective survival – one on sonic terms, is a form of commitment that obliges to Ukrainian life through mouth-on doings that engage the insurgent collectivity of shared speech.

The text is centered by the argument in a more affording way. It gathers from past and present politics, and repertoire of experiences to rethink the Ukrainian subject across the register of violent subjection. I draw from Black activist theory and cross-reference Black politics of collective creation, to imagine and point toward a project of political kinship around which Ukrainians can formulate their opposition to the colonial white habit of the Russian regime. I turn to practices of generative listening and performative writing, to trace in the inventiveness of participatory telling a justice-seeking effort. The essay leads to an idiosyncratic disruption onto questions of war and peace, and develops a statement for a confrontational position, that of anti-, which can be powerfully articulated through the affirmative politics of sound-living that it locates with Ukrainians.

POSITIONALITY

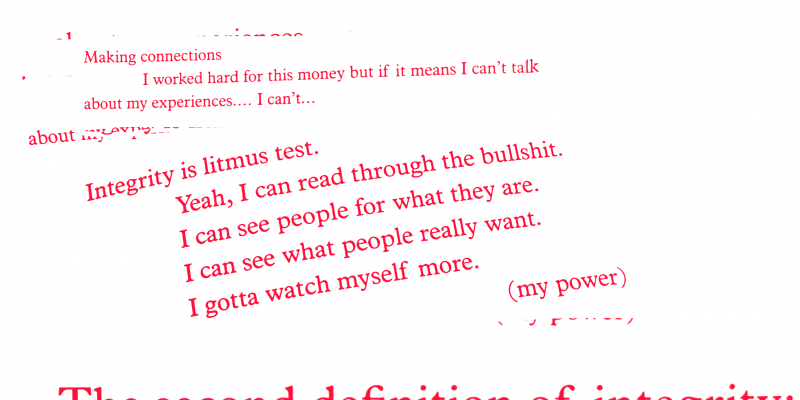

Sound as Shield is a deeply idiosyncratic essay that thinks with the troubling tangles of discontinuous worlds it creates in listening to uneasy histories and incommensurate yet potentializing resonances that lend to a more enactive understanding of the Ukrainian poetics of endurance in the duration of colonial presencing that assembles and serves the logics of oppression. I take liberties to imagine and extrapolate from experiences, allowing myself to dwell with what remains empowered by mythological possibilities existing within the argument that is not to be assessed for parallelism but grasped in the fabulation’s creation of vision. The text is a performance of writing and listening that does not shy away from uneasiness posed by enactments that I gather from ideologies, and related ethics, into which Ukrainian life has been inscribed. It becomes captured by the force of thought that escapes where it was initially ordered, travelling through and beyond the already created interspace, sites of radical will to imagine, and express through the blackened Ukrainian subject.

I write to stage a provocation, as much as to stake claims to the Ukrainian project that takes survival as a task, conjuring a poetics of difference to which fugitivity can be traced and explored in the contingent formlessness of its sound. I approach Ukrainian fugitivity as a participant, researcher, and narrator maneuvering through the uncertainty of historical time, the limits of encounter, and space of listening to attend to the truths of Ukrainian life from my own being and becoming in listening, in sound, and in solidarity. Lingering on what may come across as bad note, or a bad tone of riddling with the stance of black-white matters around which I orchestrate my narration, I perform a daring move onto a scene of politics where one yearns toward a relational contingency from which to foster common sensibilities and uncommon moments of collective struggle.

»I’m a pianist after all«, as I say it in the text, alluding to my pursuit to play with the trouble in each fragment of attention that this writing crafts.

THE SHIELD

The essay probes an understanding of a political condition made apparent in the sonority of Ukrainian life expressing itself through the creativity of speech that resists processes of russification and colonial possession. The creativity of speech, as allied to Brandon LaBelle’s account of speech as one’s being in the world by way of vibrancy and coherence necessary for emergent formations of togetherness, is more than a locus of verbality. It is a capacity to become a vibrant political subject that operates across forces and dynamics of power. (LaBelle, 2018) The Ukrainian subject of which I write here can be grasped in a unique lingual adventure of its vibrant living performed through a constant negotiation of colonial pressures located in the historical project of Russian political, cultural, and linguistic hegemony. It is a subject defined by long-term operations to sustain and expand Ukrainian life beyond and against the control of ideological master that Russianness in its orientations inflected by colonial power has been.

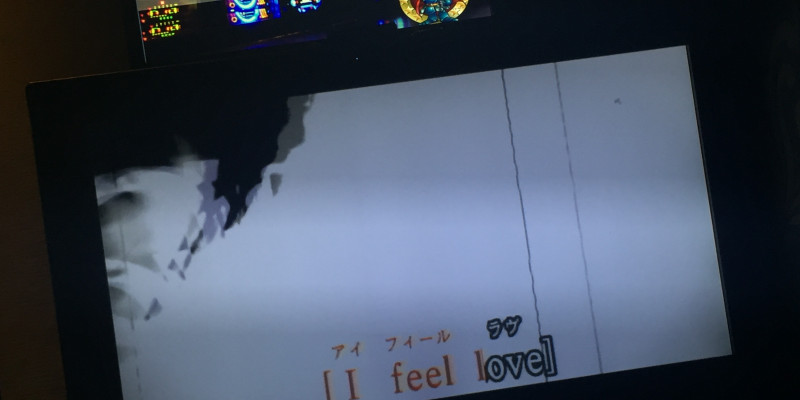

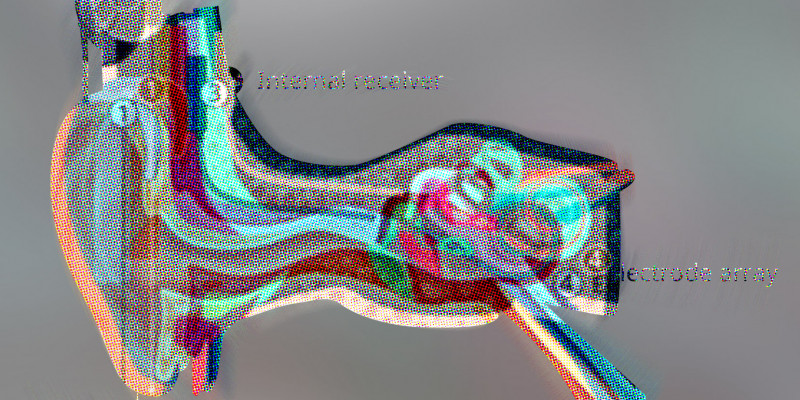

Thinking with the Ukrainian efforts to subvert hegemonies of Russian dominance, I seek to recover what has been erased by colonial visions cast upon a space of politics within which Ukrainians had to assimilate and disappear as a people, and as a sounding subject adept at appropriating inferiority determined by the oppressor. I elaborate on how Ukrainians have been crafting their way of resistance, and dissonance, through the inter-lingual iteration of subjectivity defined by hybridity rooted in the creation of mixed language varieties known as Surzhyk; and how they’ve been making the practice of everyday speech an active performative operation. Surzhyk is discussed as a practice by which Ukrainians fostered collective self-making, creating the »space of appearance« (LaBelle, 2018) and nurturing conditions for Ukrainian life to emerge and flourish in sound. Labours of speech are understood as a necessary investment in the task of care that takes risks of one’s imminent disappearance into account, investing in a politics of contingent and continual appearing that is sounding, vibrant, commoning. The essay ends up becoming a reflection on this process of laboring toward an ongoing collective reimagination of existences, a future of Ukrainian recovery, that I orchestrate through a dramaturgy of »generative listening«. (Voegelin, 2019) The recording of my father, which features him speaking Surzhyk in the occupied territories of Ukraine where expressions of non-Russianness are heavily policed, serves my critical and creative inquiry.

I take the recording at its sound, both in the historical scope of things and in the real situation of its illegal status, seeking not to comment on what I hear but to inhabit the heard and invent with it.

In a more formal part of the essay, I hypothesize that engagement in the collective imagination and fugitive formation of community through a mundane way of sharing a collective speech that involves the task of commanding the insurgent Ukrainian life bears the potential of serving collective self-defence amidst destructive forces of structural whiteness that I locate with the Russian regime rendered through its histories and lexicons of mastery. What is the protocol inherent in the operation of Surzhyk that supports a pursuit of messy experimentation by which the process of russification could never complete itself? And how can we hear across the uneasy resonances of knowledges inciting this incompletion? Thinking with the combative gestures of Ukrainian estrangement and alienation from the promise of colonial relation, I position Ukrainian »speech and action« along the »spectrum of poetic weapons« by which to fashion a mode of everyday survival: to build a shield, a kind of sonic infrastructure marked by self-organized radical care. (LaBelle, 2018)

I follow from gestural logics of insurgent life (Manning, 2016) and techniques of relation and fugitivity (Glissant, 2010), to evoke a politics of errant action undertaken to craft resilience to the continued violence of a lived colonial project. My understanding of the Ukrainian struggles is deepened by the schema of this action to consolidate a confrontation with the oppressive condition found in the white habit of the Russian regime replete with desire to reduce Ukrainian bodies and lands to the category of the inhuman. (Bazdyrieva, 2022) Warning against the Russian reduction of the Ukrainian subject, I navigate the ecology of the Ukrainian experience through a shared sensibility to Russia’s politics of conquest and subjugation that lends to a greater sense of unfreedom which has shaped Ukrainian life. The text is crosscut with the history of Russian entitlement and Ukrainian subjection from which a new understanding of what Ukrainians are living now (and how they are resisting what they are given to live) can be sought out.

In the second less formal part of the essay, I tie my deliberation to the current politics of war and peace, in which the afterlife of Russia’s expansionism, extractivism, and aggression is shaped by new imaginaries of dispossession (both of land and sovereignty) unjustly imposed on Ukrainians. Attending to the ongoing cycle of injustice within which Ukrainian futures are ordered, I write to contest the ideological architecture of confinement to which Ukrainian life has been bound. I enter the scene of »lived non-fictions«, worlds already and yet-to-be lived, in the journey of generative listening from which I fathom Ukrainian tragedy as it comes to resound through sonically working efforts of ordinary Ukrainians like my father, like other fathers talking to their daughters their mothers. My intention is to construct transindividual reality in a contingent practice of listening that ear-witnesses with care the underheard echoes of the Ukrainian experience, making thinkable and knowable the sheer force of Russian colonialism in all its whiteness.

THE UKRAINIAN SUBJECT

In her essay on the political imaginaries of Ukraine, Asia Bazdyrieva makes a compelling case in positioning the Ukrainian experience within the imperial grammars of the inferior subject. Examining the histories of resourcification and logics that invest in the categories of subrace, underclass, and inhumanity, she invites a greater attention to systemic violence that perpetuated the relation of mastery over Ukrainian life. Rendered as a territory with extractable resources and »inhuman subjects«, Ukraine with its people has been imagined and approached as a »component of material exchange«. Its human and nonhuman populations, soils, minerals, and other ecologies of life were subjected to extractive economies of imperial-colonial formations, both West European and Russian. Falling prey to what Bazdyrieva terms as »dual colonization«, Ukraine remained violated, resourcified and absorbed into the violent and repressive politics of conquest within which white colonial desire continued to resurface in various ways and forms. Ukrainians were made captive to the imperial-colonial conditions that incited what we witness today in the resurgence of military aggression against Ukrainians who found themselves in the face of yet another “existential threat”. (Bazdyrieva, 2022)

Historically Ukrainians were caught between the competing powers of dictatorships that ordered the Ukrainian body to a lesser humanity. Hitler’s Nazi fascism and Stalin’s man-made famine-genocide (Holodomor) are enough to arrive at this uneasy truth: the death of millions of Ukrainians who were purposefully exterminated to further reinforce the very subjectlessness of their existence. As Timothy Snyder suggests, Ukrainains were stripped of dignity and made into currency between the imperial-colonial regimes that sought to achieve genocidal war aims. They were at the center of imperial attention, displaced and dehumanized in the pursuit of value for the ongoing simultaneity of colonialisms. (Snyder, 2012) In the Nazi era, Ukrainians were subjected to racialized logics and practices that deepened their inferiority complex. “When German occupation came in 1941, Ukrainians themselves made the connection to Africa and America”, as Snyder (2015a) writes, foregrounding collective consciousness informed by a shared encounter of Nazi racism. (p.18) And as he (2015b) also asserts, bringing into view an ideology of mastery and possession through which justifications were made to acquire and exploit Ukrainian bodies and lands: »Ukrainians, above all, were conceptualized as blacks or as Africans, since their land was seen to be the secret to German self-sufficiency as the keystone to a new German empire.« (p.697) »The idea was to create a slavery-driven, exterminatory regime in Eastern Europe with the center in Ukraine.« (Snyder, 2017)

Snyder’s study of imaginaries that fostered atrocities against Ukrainians can be read in tandem with Myroslav Shkandrij’s careful examination of the dehumanizing character of the Russian imperial entitlement. In the Russian imperial imagination, Ukraine was portrayed as a reserve borderland available for harnessing, while Ukrainians were seen as uncivilized »others« readily addressable in their inferior status. Called by various derogatory names including “white negroes”, they were expected to do plantation-style agricultural labor in service of Russia’s imperial dreams. (Shkandrij, 2001) The Ukrainian experience of forced collectivization and engineered starvation is direct proof of this aggressive commitment, deeply invested in the exhaustion and violent coercion of Ukrainian bodies. (Appllebaum 2017) As Raphael Lemkin contends, the violent disposal of Ukrainians has been a lasting characteristic of the Russian regime that kept renewing itself. (Lemkin, 2008) And as Serhii Plokhy argues, Russia’s most recent attack on Ukrainian life is an old-fashioned attempt at sustaining the exploitative expansionism of imperial statehood and its colonial enterprise. (Plokhy 2023)

These histories, relations, and grammars of oppression call for an apprehension of the Ukrainian subject in a larger politics of physical and ideological assault on its being. Formed by the wretched conditions of conquest and genocide, the Ukrainian subject is one that had to act through modes of self-recognition, self-preservation, and self-making to survive and endure the ongoing, inherently diagrammatic operations carried out to destroy it. The politics of Ukrainian endurance, as I want to argue, extends beyond the observable gestures of guerrilla tactics and defensive moves that revolve around straightforward counteroffensive responses often associated with Ukrainian resistance performing on anti-colonial and now anti-neo-colonial terms. It reaches all corners of individual and collective life that seeks to break through the reign of colonial powers that objectify, resourcify, and confine it to subjugated existence. I want to foreground a particular lingual-sonic aspect of this life, which must be grasped against and alongside the scenes of terror and subjection within which the Ukrainian political subject emerged and from which it interrogated the lived world.

OPACITIES OF INSURGENT LIFE

Russia’s all-out war on Ukrainian life foretells the repeated history of framing the Ukrainian subject as a threat to the order that the code of Russianness is meant to protect and make operative. Following the first weeks of the 2022 invasion, the Russian state-owned news venue RIA Novosti published a statement in which justification for killing the Ukrainians in large numbers was made part of a call for Ukrainian nonexistence: »Ukrainianness – is a fake anti-Russian construct that is devoid of substance.« (Sergeitsev, 2022) This deeply programmatic public statement, affixed to the negation of the Ukrainian subject and subjectivity, speaks to histories of tyranny and colonial rule that are still lived and experienced, and that are constantly traced in their afterlife. Despite hard-earned sovereignty and promise of freedom, Ukrainians remain subjected to possessive ideologies and practices consistent with the white habit of the Russian regime.

In thinking the ongoing subjection of Ukrainians, I follow black scholar Saidiya Hartman who examines how subject-making extends to the afterlife of experience. The experience of slavery of which she writes is lived, and is reconceived, through Black personhood that remains defined by slavery despite its formal abolition. The continuities between slavery and freedom are not effaced but on the contrary reinforced through new and possibly contingent modes of domination that persist in the afterlife. Freedom is made a condition that generates the vast plenum of unfreedom, routinely and lastingly investing in historical injustice instead of combatting it. (Hartman 1997) It is from this generative politics of un/freedom that emancipatory desire continues to proliferate across the forms of black insurgency, fugitivity, and collective self-defense; desire outspoken and outexpressed in the far-reaching of a black dissonance always already stirring what stems from normative orders of whiteness, stained by complicity with imperialism, colonialism, capitalism, and the conjoined violences and harms that these systems produce.

In her book on normativity and the politics of emancipatory “minor gestures” that undermine it, Erin Manning attends to the creative and affirmative impulses of »insurgent life« that resists to settle into articulations defined by forces controlling it and submitting to capture. Taking neurotypicality and whiteness as these imposing forces, she develops an argument for an essential variance and incompatibility with promises, tenets, and sensibilities harnessed to serve the operative logics of violent imposition that delimits bodies and possibilities of life. Life coheres with minor gestures that invent »modes of life-living« to defy the ordering relations, dominant logics, and fixed normative expectations. It is always in the process of breaking through, of scrambling the codes and spilling over into the world, of bundling in all the richness of its atypical expressions. Unbounded and unpredictable, and for that threatening, life that resists to be measured against the standard of typicality and white dispositions is always of creative, generative potential. (Manning, 2016)

In this sense of politics, insurgent Ukrainian life is life that is in excess of position that makes it bound by historical code of serving the Russian master, and protocols for typicality that mastery creates, those within which any atypical expressions of the “other” are to be regulated and controlled. It is life that invests in un-controlled-ness, seeking in spontaneity (and freedom it generates) an ongoing escape – life beyond capture by antilife that is contained by repressive and totalitarian dimensions of its reality, truth, and language. In other words, it is relentless persistence to thrive, to break with repressiveness through bursts of expressiveness, revealing an inexhaustible reserve of minor gestures, surprises that are never to be seen but fathomed in the unseen, in what lurks beneath the constraint of identity or certainty of what it must become, of what it must escape to be in a lived metamorphosis of its Surzhyk, of its Surzhyks.

Surzhyk is where I listen to detect Ukrainian life emerging from thickets of history, memory, and politics. It is the language within which my Ukrainian »I« was born and made a thriving – a living on sonic terms probed in secret across many of us stiving to cohabit the worlds we create by criss-crossing the stitches of russification impressed on our bodies, our voices, our sounds, trembling and tearing together and apart. My father spoke Surzhyk, and so are his parents their parents too, across generations of us who could not meet their master in the eye but confront the ghosts of his being in the ear, in the shadowing of master sounds that we had to overcome to stay alive in the process that served the most probable way of our perishing. Russification has been a condition of Ukrainian life discounted by violent cravings of the Russian regime but reclaimed by colonial needs of Russian benevolence that sought to keep it living, in service of Russian “greatness” that the russified subject had to evoke and convey.

Ukrainian Surzhyks, commonly unified into the term Surzhyk – a range of mixed language varieties that combine Ukrainian, Russian, and emergent word-formations, can be said to be the spoken voice of Ukrainian life, tainted with negation of its being that russification entailed but inflected toward an affirmation of its becoming in the process of inter-lingual experimentation performed through possibilities enabled and lived in a plurality of formless existences of the sounded body. They are the site where relation between the oppressor and the oppressed is navigated and transformed, not only through the linguistic intent of potentializing novelty but also through the acoustic reflection of confronting the authority, of standing up to conformity by investing in hybridity, variance, and complexity.

In thinking the poetics of experimentation that spans the formative process of Surzhyk, I draw on Édouard Glissant’s concept of opacity that makes graspable the condition of emergence that defines the inter-lingual iteration of experience. Positing opacity against the objectifying logics of transparency that force the world into reduction, universality, and separateness, Glissant develops an argument for an entanglement of relation defining the “diversifying” and “multiplying” poetics of being, of becoming an ever-changing dynamic assemblage of differences. Opacity structures Glissant’s discussion of creolization, a condition for an ethics of relation beyond domination, that makes room for variability, volatility, and versatility within the entangled continuum of Creole life. The creolization of life, of language, and of collectivity cultivates a commitment to resistance that celebrates the rigours of interplay, of conjoining and intermixing, of forging a path to freedoms of novelty through the making of the creolized self. (Glissant, 2010) I think with Glissant to locate a poetics of confrontation that seeks a distinct advantage in reshaping the relation between the colonizer and the colonized toward a sustained constructive experiment in hybridity. Surzhyk is a manifestation of Ukrainian hybridity by which Ukrainians resisted to be absorbed into the russified subject, building a sonic arrangement with life affirming itself in every spoken effort of their vibrant living.

The notion of vibrancy is particularly useful in conveying a deeper sense of energetic investment in the oral poetics of Surzhyks that Ukrainians produced collectively, participating in the spoken of life lived, shared, and upheld as the promise of self-making, and self-shielding against the prospect of disappearance. I gather from LaBelle’s discussion of vibrant subject fashioning the world, and worlding, pressing with the unseen trajectories of its presence. Vibrancy defines the intensity of relation invested in opacity, thickness, and deep resonance through which to meet the world of sonic terms, in ways of revealing and sharing that are politically committed and ethically grounded. With vibrancy, LaBelle extends the potential of the sounded subject to a relational field in which communities (and their resistance politics) are forged through lived sonorities, listening sensibilities, and gestures of sharing that incite new, more fragile modes of togetherness. (LaBelle, 2018) The political project of Ukrainian Surzhyks must be seen within this frame of existence, in the making of life on sonic terms, in the breathing of it performed vibrantly and vigorously, in the cacophony of voices shared across the Ukrainian common, and in the expanse of this sharing empowering the force of emergent relation from which to build collective defense against colonial takeover that reaches the body, the language, and the living of it.

OF GENERATIVE LISTENING, OF GENERATIVE TELLING

I make my listening a living memory of my father who left me with a recording to which I pay many returns. It is a recording of us sharing a moment in our kitchen that would later become our hiding spot where all that shielded us from the war was our sound, our way of Surzhyk, torn and scarred, and laid bare in a taking of our breath.

I bring this recording into play not to recover an intimate history of my family but to discover a shared living of this history that a generative effort of sounding and listening may afford to intensify. In what follows, I perform the experience of Ukrainian life at the brink of survival, giving this performance both the strict sense of the word and loose interpretation informed by the poetics of truth-telling. My »telling« is grounded in a wider range of references and inspired by a greater sense of solidarity in this lived moment of Russia’s war against Ukraine. I become interlocutor to what I hear and imagine to be heard, engaging with the material through a series of lived non-fictions that I create to speak back to my understanding of the Ukrainian subject and its broader political performativity. My approach is inspired by Salomé Voegelin’s argument for a »writing in fragments of listening«, which entails an idiosyncratic undertaking that sets new terms for a »rigorous criticality«, embracing the task of auditory imagination and fabulational practice. (Voegelin, 2019)

As I navigate the recording, I write toward a political possibility of the worlds I discover in the sound and sounding of my father’s voice always gesturing toward affirmations of shared collectivity. My writing is joined by the promise of these affirmations, extending from the depths of collective being to trajectories of becoming, futures to be imagined and lived in the ruins of the neo-colonial war brought upon Ukrainians fighting not only for their right to live but also for their right to be worth living, to be worth saving. I listen deeper into the question of worthiness as it makes itself posed in the cry of the Ukrainians who ended up being in the territories now occupied by Russia, in the terrorscape that these territories were made part, asking how their cry is deterred by the politics of peace that grants Russians the right of land concessions and invests in anti-war benevolence that does not end the war but on the contrary feeds it, perpetuating injustice and historical violence. In questioning the current politics of peace that subjects Ukrainians to forces and futures of unfreedom (conquest, occupation, dispossession, cultural genocide, etc.), I elaborate on the way of Ukrainian response that confronts this politics and cuts through it. I think with Etienne Balibar’s notion of anti-violence, as a position of legitimate confrontation that does not have to circle back to (counter-)violence or non-violence, to war or peace, but operate from the third conceptual ground, the position of relation, that of noise in the Serresian sense. (Balibar, 2015) I cross-reference Michel Serres’s concept of noise as one defining a relation of interruption, provocation, and interference; and a field of emergent force that propels creativity. (Serres, 1995) It is within this confrontational stance of emancipatory insurgency that I argue for a mundane and pragmatic way of doing politics: the way of sounding and sharing speech, of gesturing the embodied rendering of care that the vibrant collective body strives to perform.

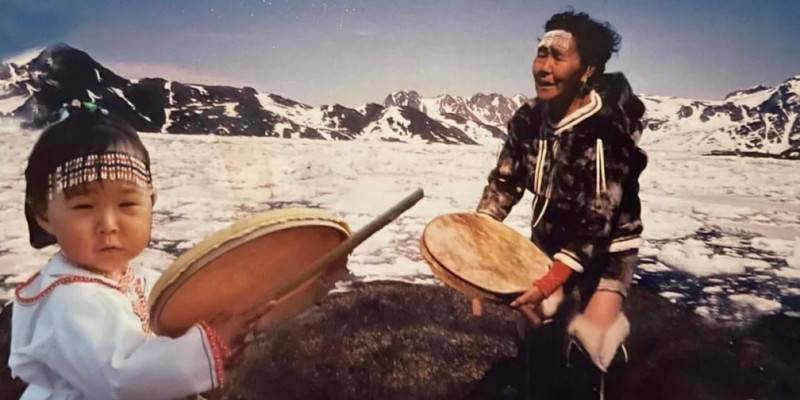

I want to make thinkable the sounding project of Surzhyks that exposes Ukrainian life’s vitality, the errant journey by which Ukrainians figured themselves against the overwhelming force of russification following them across the everyday and through many years of Russian dominance. In evoking this process of ordinary routine commitment that keeps in touch with reality, I turn to the metaphor of Ukrainian kitchen as one that conveys the feeling of shared life – and shared war. Ukrainian kitchen in my text is a term that both names and alludes to household space that kitchen is. In the occupied territories where expressions of non-russianness are publicly suppressed, kitchen becomes a place of refuge in which hidden Ukrainian life continues to flourish. In a more real sense, of course, kitchen is hardly a safe place anywhere in Ukraine where every home is turned into a potential target. I take up kitchen as a conceptual construct and material space, while also as a symbol of Ukrainian resilience and collective resistance.

The text is a deeply personal narration that folds into violent histories and emancipatory struggles and becomes traversed by possibilities for political kinship invested in a heterogeneity of effort and imagination. It composes with the potential of constructive and diversified commitment, turning to rigours of Black thought and generating a crossing where poetics entangles experiences of lived oppression. Developing from the future-forwarding promise of sonic fiction, this writing co-creates with Ukrainian dreams to be, commanding against futures denied and destinies given, toward lives to be lived: a stance of collective (Earthly) survival riddled with the Ukrainian arts of endurance.

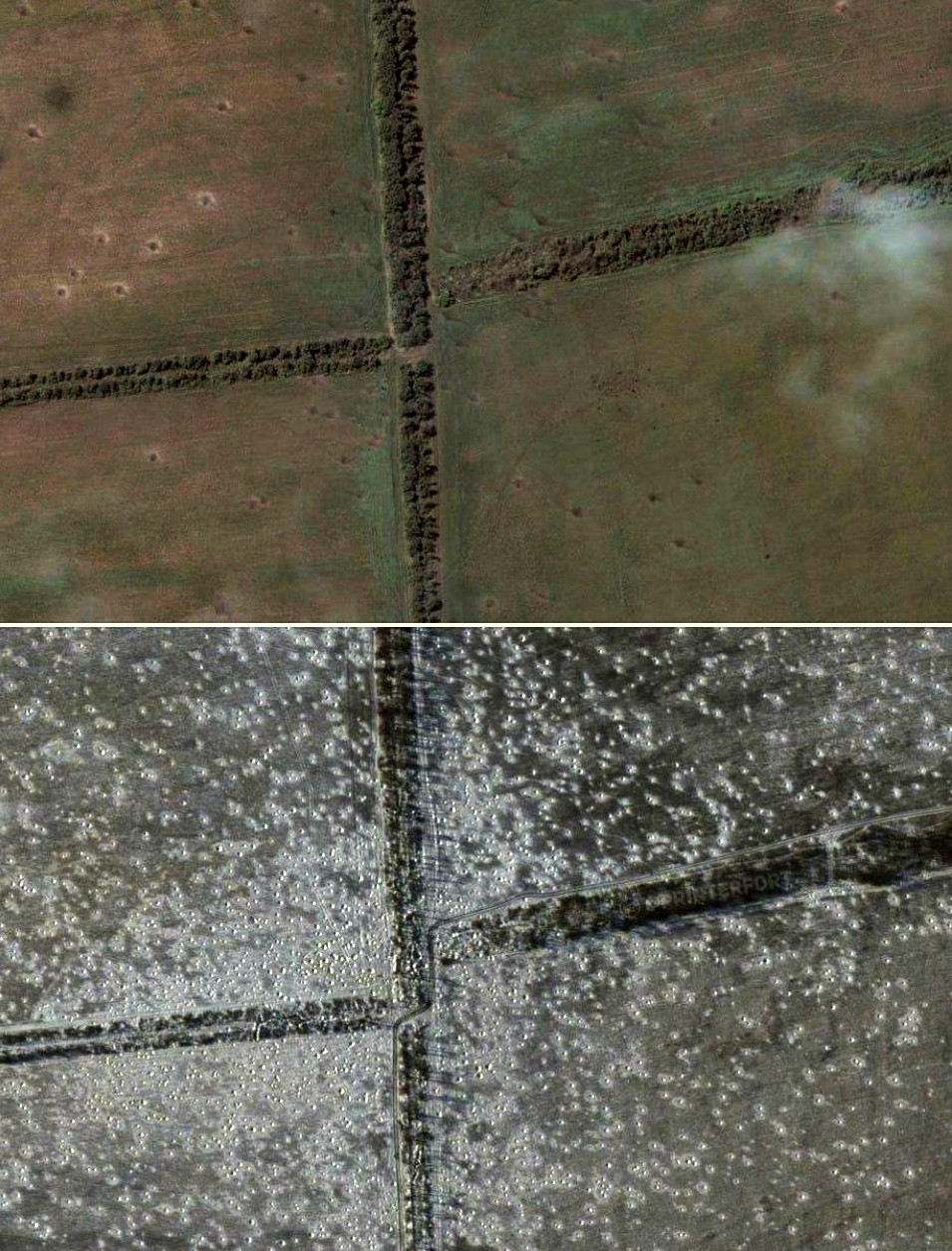

Black Earth in the text is a direct reference to Ukraine’s fertile black soil (chernozem) around which the Ukrainian colonial subject has been historically conceptualized, and settler economies arranged and practiced. (Snyder, 2018, p.119). Conceived as a »breadbasket« of Europe, Ukraine was, and is, purposefully objectified for the needs of the master and approached as a possession from which to extract maximum profit. (Bazdyrieva, 2022) Its destiny has been long prescribed by the unwritten contract of duty to imperial mother land – a normative expectation by which Ukrainians are now called to submit to the inherently white colonial imperative of »Russian peace«.

Speaking to the given and dreamed, the text attempts to break free from the confines of history toward the realms of non-history. Home to Black Earthers, Black Earth is imagined as a long-dreamed habitat and shelter where Ukrainian survivors of Russian invasion can keep themselves safe in the deepest black soil horizons, the undergrounds of their working Surzhyks, while the aboveground remains contaminated with landmines and unexploded munitions; seized and wiped out by the war, turned into a Chernobyl-like zone of exclusion.

A crossbreed of fact and fiction, truth and speculation, manifesto and myth, the text is the creation part of this research-creation project in which I want to rethink sound toward its ethical doings which get one through the day, life, and history, and, as in the Ukrainian case – through the very war.

A FRAGMANT OF LISTENING: LIVED NON-FICTIONS

prisoners

I am not with you. I am with you, in a tiny kitchen where we eat Azov Sea gobies, catch of the day. Me and you, together, and a cat. You speak to me as usual, like father to daughter, in our secret language prohibited to be heard. You call in me a Ukrainian, not knowing that I already am, a foreigner on this land they now call russian.

Crimea is no longer a paradise but a torture camp where they line up prisoners and feed their bodies to fish. To Azov Sea gobies. On the 300th day of war that started 9 years ago, in our kitchen from which we could hear sounds of russian military flooding the streets, loud voices in vehicles, cheering to kill us, all in us.

In you. That day, when I was with you, we did not know that this war can reach us so soon. That day you spoke to me like every other day to remind me that your sound is my sound is my pain. And we are in it, and a cat.

They seized Crimea, holding us prisoners of war. Prisoners of worries who now count time in warheads depleting our defenses, families across the east, their families across the losses, limbs.

Us dragged to the frontline of one’s imperial mission to which we are held to imagine a response. To put up air defense. To grow wings and hide in seconds to falling bombs.

In kitchens, under the tables, like in a movie hiding from a killer holding us hostage. The entire nation under. Taking cover.

Father, I am not with you. Not anymore but I am with you. Speaking from the under, from below (LaBelle, 2018), out in the open. To the world. On behalf of every Ukrainian who could not make it.

sounds to which I hold my breath

We breathe together. In the space of our kitchen at dinner table we create a dream to be. What if we could recover our borders, reclaim our lives, regrow our roots. Become a tribe in sounds we planted illegally, we watered daily, and cared for. In the living that kept us alive. What if.

our war is your war

I imagine you, a listener. Of our story born to tears we cry mourning our dead, our warriors, fathers & sons, mothers & daughters, boysgirls. Us. Our alien corpus (Schulze, 2018) we sound, each other, and you. Our volume we carry it carries drops of our sweat, pressures of our breath, insistence of our being... Salomé, I want the world to hear me. I insist. As you do, in your books. Volumes share us to the world, of the world they make us, us. (Voegelin, 2019)

Our war is your war. Not because it can reach your tiny kitchen, your distant country. Not because it can point at you, our cry to your ear. Our war is your war because the struggle is there, and you are part of it. You are of it. You are.

thickets

I am not an anthropologist, but I studied with one. To become an ecologist detecting footprints of the mouth. The illegal pursuits of escape and survival which make private protocols of Ukrainian life: us held by desire to stay alive in sound of which others make us a threat.

My father was there for me to record his (protocol), for my greater project of re/collections. His Surzhyk, language that we contested and shared but feared to speak on the streets. Its sound, thickened with our breaths and our burdens. Something very ordinary and unimpressive, happening all the time. Ukrainian fathers talking to their kids, hidden in their kitchens, ignored by the world.

Of Ukrainian fathers murmuring our struggle sprouting of their kids’, of their kitchens’.

murmur

I imagine murmur as a striving breath, a crisp air that moves and grooves to slow erupt through. To rigour its way into a tight circle. To whisper its way.

Serres writes of murmur as of a genesis of forms, of a turbulent pool of the possible, of a primal multiple that rolls, whirls, and propagates. Of a process of cancer cell. Of.

“In the beginning is the echo: murmur”. (Serres 1995, p.70) An expansive plane, and one’s growing planet. Life and death at once. A fog of war, that blinds and bloats, distorts and bends to its will, to its illness.

A massive doing. That makes us and make of us co-constituents.

A murmur of my father was a mundane path, a mouth-on task of saving our faded language, silenced body, erased life.

Proliferating and prophesying the echoes of aborted beginnings.

forest

I find myself in the forest of echoes. Struck by the force of them weaving into each other, twigging and branching in all directions, outbreaking and turning into an emergency site to which now everyone starts paying a visit. I am here too. Revisiting, on my 300th trip. To collect evidence. Of ruthless violence. Of buried truth.

Bare wall of hungry hands. In a shared echo of flickering voices swallowed by the forest where they are gathered to be burnt. A sound nakedness of genocide.

We are born to this forest. We have lived in it. For 300 years of russian dominance. All of us hunger struck, robbed of chances at Ukrainian life.

Our many Surzhyks, languages of ancestors, are our dirty hands. We work them in kitchens, we work them in soils. We set them to guard us in childbed. In times we make our life to be. In Black Earth.

Our earthly becomings are messy. All but uniform. Fruits of decomposed roots that end-us in the same old-forest.

XX23

We are year XX23, deep into terrorscape of russia’s war. Into soundsky of the settler, dropping warheads of perfect speech onto fields of our-wild dreams, our-savage Surzhyks. Seeding white sounds at the back of the tongue we must speak. We must work. For a new Dolgoruky who imagined us sweat and burn in the sun, »bronzed face«d in his landlord empire. (Shkandrij, 2001, p.79) Black-boned in the grand mothership.

Black Earthers

Let me linger on this bad note of black-white matters. Let me keep it pressed. I’m a pianist after all.

»…history of colonialism … involves denying that another people is real. It involves denying that another state is real… That is, of course, the premise of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine,« (Snyder, 2022) this is, of course, the promise of white habit.

Ukrainians, »a people by the mythmakers of the empire« (Shkandrij, 2001, p.20), Black Earthers, are deep-foreign bodies envisioned for slave. (Snyder, 2017)

I like this myth of Black Earthers that we make of ourselves. Another type of Alien Nation, a living kin. A shared consciousness of alienation, of which we grow our sounds, our dirty Surzhyks, our worked-out hands.

We don’t roam a sci-fi nightmare (Dery, 1994), we test kinship live-walking, on fires. Kinship is held for us in each russian rocket destined for a war of extermination in which our chances of survival are compared to nil. Kinship of humanoid aliens (Schulze, 2018) limping their way to prosthetically enhanced futures that are not made for the Weak.

I think back to the weak and a weapon of weakness (LaBelle, 2018). I think back to Black Panthers who self-defensed, and I imagine them gasping for air, in silence, standing still, in protest of motion, in denial of reality, in defiance of sound. Counting to 300 years to be heard, to be witnessed, in their longing to live up to tomorrow, to make it to the other side.

Is there tomorrow? I ask. Can there be? »Can a community whose past has been deliberately rubbed out, and whose energies have subsequently been consumed by the search for legible traces of its history, imagine possible futures?« (Dery 1994, p.180) Can it, Black Panthers alter-governing and future-centering their way, their wish? To make futures of their own. No longer steeped in nostalgia. No longer dreamed up by ghosts.

ghosts

We know they are there, our ghosts. Makers of same old-forest. Breeders of our destiny. Hard drinkers of black milk. They drink it at daytime they drink it at night they dig our future they mark our land. Planting mines in our crop fields (Rybarczyk, 2023) bringing famine on our children. Like they did in the past, starving our mothers to death and replacing them with thousands of well-bred bodies. (Applebaum 2017) Bodies whose sounds haunt us, refusing to lie still. They bleed off our mouth, spilling into our tongues, erasing our Surzhyks from the face of Black Earth.

leaking truths

This war is a war of sounds. A pitch-black scream of our ancestors against white noise.

I struggle to make it sound, this war. I cross into its frontline, with a recording of my father recovering his Surzhyk from the depths of Black Earth. I think of his kins, the Others, who reclaimed their truths, radical pitch-black struggles of which no one could have possibly heard except their kids. Ukrainian fathers talking to their fathers, in kitchens destroyed by russian rockets falling off the white sky.

A haunted presence of their abducted bodies. A future that never was. A future that there be, a pitch-white war crime.

We call for an end of it. Panthers of Black Earth, digging out our lives from the rubble of blown-up homes.

I turn to Eshun, a grand master of recovery efforts with whom I imagine mixologies of insurgent lives, and new guerilla tactics to make it out of the forest set on fire by those who wanted us clear-cut. Daydreams of survival sonically thought and overthought. (Eshun, 1998) High impact sonic fictions, »bits« of blown-up mind. (Schulze, 2020).

Bits of our limbs torn by a detonating calm of acceptance forced upon us. The given we are given to bear, the white-skyed air we are buried to breathe, the air that’s killing our black soils, our father tongues.

Those who control »the living past« control »the living future«, a high-stakes game setting the motion of the beat. (Eshun, 1998). A heartbeat whose throbs run through our exhausted bodies. Whose past are we living? Black Earth descendants carrying pieces of russian rockets, bits of high-fire nightmare in-surgically grown into the bodies we are now trapped, unable to rid us of firing noises born to the russian sky –

the 21st century experiment that everyone watches on their youtube channels, desensitizing the eye and detuning the ear to our pitch-black scream. (Iakovlenko, 2023)

theft

This is not a sonic fiction. This is an air raid siren test. Did we pass it? Hiding under the tables of our kitchens that cannot shelter us from the white sky dropping projectile memories we’ve already lived for 300 years of grand history. A history of fire-washed beginnings that they made of us. Engineers of fantasies we never were.

Who are we, Black Earthers, whose children were starved to death to spare their lives to new roots? Who are we, Black Earthers, whose mothers were abducted to go missing? Who are we, Black Earthers, whose survivor bodies are still getting ripped and mutilated by fragments of fallen war-heads that now make our shared-heart?

This is a sonic fiction, a refusal to reconcile with fictionness, with the false of grand peace they demand from us to make peace with the 300th year of stolen futures we count for each of our fathers.

UkrainoFuture

It is year 20XX, the year when we learnt to extract our Surzhyks from the skies of white noise. We finally built the air defense system that kept us breathing in underground chambers we architectured in our black soils. Chambers that could withstand forest fires.

My father is a fire fighter, one in charge of water bomber fleet. Rescuing flickering voices swallowed by the forest, our daughtersons, motion captured humanoid aliens reliving yet another russian-made disaster. In 2023, they were »hostages of the situation«, and so are in 20XX. Lost crops »in one of the largest black soil zones«. (Stakhivska, 2023)

I am listening to the stuff coming out of Underground Chamber. The motion of the Heartbeat synthesized into new pulse, to prevent failure in the next attack. A weird thing that we’ve been working out all these years, trying to save our dying world.

underground kitchen

I am back in the kitchen, with my father, and his story of our ancestors who spoke Surzhyk and lived in the Severia region that stretched further than today’s Ukraine.

We make a hideout, dragging 300X fire-blackened walls, and record stories about Azov Sea gobies, species that went extinct when »little green men« (Shevchenko, 2014) seized the land, and built in our Sea their disaster bridge.

This war is a war of sounds. Us buried alive in underground kitchens where we are sheltered by our scream.

threat

Ukrainian life is not strictly of the human (alien). It is life of becoming-, of living-expanse, of echoing-truth... life as it can be, of many, growing volumes of sounds heard, underheard, overheard.

Of the totality of noise. (Serres, 1995).

Of that what constitutes a threat, a life-threatening- life so to speak, in its gestures of invisible formlessness.

»Stop it!« I hear it from all directions, the voice of a settler teacher shaming me for my improper speech, my piercing sound bothering the russianness pristine shared by the entire class. By the entire nation of (neo-) Homo Sovieticus into which they made us (speak!).

weapon

I am in the warzone, in field trials of big sounds. To which we are made targets, on battlefields.

»In situations of acute violence or duress… sound becomes not just instrumentalized, but weaponized”. (Daughtry, 2015, p.165) Sound becomes. Its own kind of weapon

puncturing the eardrum, concussing the brain, terrorizing our being. Wounding and making wounds and making worlds of wounds. To generate fast stream of devastation.

This war is a war of sounds, our fallen lives against grand opus of russian peace (-fullness).

shield

I imagine our shield. A thick layer of Surzhyks nurturing the exhausted black soils, lexicons of the mouth (LaBelle, 2014). We speak them at daytime we speak them at night we grow our future we save our land. Impressing our stories with the lasting seal.

Our shield is our weapon, made of a “third” point: across a two-point scenario of war-peace dichotomy. A fading signal between the existing ends, a third term across »being« and »non-«. An odd term of »anti-«.

Noise is of anti- (Serres, 1995). And so is peace we make of our war. Is of anti-.

Antipeace nurtured on popping drops of antiviolence (Balibar, 2015). On pops of sounds making shields of soils we save for wild plants.