Sonic Writing

Introduction

Being one of many self-taught practitioners in the use of digital audio, I consider in this article which changes the use of the computer and audio software have brought about in my previously instrumentally-based compositional practice. I propose that integrating digital audio into composition for live and acoustic instruments and voices has brought fluidity to the compositional process and to the formulation of presentation formats, opening the range of contexts available as content and as professional milieu. In my work, this practice has softened some binary relations, with electronics providing, for example, the potential for an expansion of vocal ranges and a rejuvenation of the expressive concept of vibrato. These tendencies towards expansion and proliferation of methods and contexts may not be common to all computer music, but are common within the artistic environment of homemade electronic music.

Computer music and electroacoustic music are terms that grew up around technology-focused research centres and large publicly funded studios run by teams of composers, programmers and engineers. Since the 1990s, however, affordable audio equipment has become increasingly ubiquitous, due to the commercial viability of hardware and software. Contemporary electronic music has accordingly undergone a digital transformation in the hands of composers and musicians working from their own homes, private studios and laptops with commercially accessible audio software and hardware, acquiring a level of user proficiency that enables independent creative work without necessarily requiring the support of considerable engineering skills or training. (Cascone 2002).

The thrust of my account is directed to describing, from a composer’s point of view, an excitement about the fluidity – of working processes, of materials, of resulting sonic textures – available from working with digital audio, and the task of aligning such a form of composition with the work of notating for acoustic instruments. Comparisons between these modes of composition arise not from the desire to have one replace the other in my working practice, but from a commitment to maintaining both, most often within the same work. Such repeated attempts at a more or less integrated compositional practice for and with instruments, voices and electronics are ubiquitous within contemporary music today, and I see this ease of oscillation between modes of composition as vibrational in the sense that composers seem to develop a muscle for moving between them.

Sonic writing

I use the term ‘sonic writing’ to summarise this field of work in order to propose that the link between sounds and composition is both one of notating (writing down) sounds and of allowing sounds to form the work and its field of potential. Sonic writing is, then, not only a practice whereby a composer writes down or fixes sounds, but is also a process through which sounds entering a work determine the composition process. Proposing this dual flow in the way that sonic art arises enables the notion of musical composition to depart from the one-way trope of the composer authoring musical works de nihilo, acknowledging the fluidity with which external contexts and contents enter into sonic artworks and are read into them by audiences.

In this context, writing is to be understood in a broader sense, not tied to musical notation. In this broader sense, it is unproblematic to speak of a composition that has no notation (an electronic work stored digitally, for example). Even an early definition of composition seems pre-destined to accommodate this, requiring only two or more sounds, arranged successively or simultaneously, to somebody’s satisfaction:

Composition consists in two things only. The first is the ordering and disposing of several sounds...in such a manner that their succession pleases the ear. This is what the Ancients called melody. The second is the rendering audible of two or more simultaneous sounds in such a manner that their combination is pleasant. This is what we call harmony, and it alone merits the name of composition.

Jean Benjamin de Laborde, Abrégé d’un Traité de Composition, 1780

Using the term ‘writing’ to describe a combined practice of composing for instruments and with audio may seem to favour the technical drawing of notation and its traditional tools of pen and paper, tools that it has in common with verbal text. In as far as software programmes for musical notation, digital audio and word processing meet in the computer, however, the expanded sense of ‘writing’ described here is able to subsume a highly contemporary, integrated workflow.

I support my reflections about my own sonic writing practice with the term écriture. I mobilise this term in order to draw on the expanded sense that resonates through Hélène Cixous’ use of the term écriture féminine as writing in an/other language (Blyth, 2004). Departing from a biographical perception of French as one among many of her childhood languages, in which she later, as an adult, maintained a productive sense of ‘foreignness’, Cixous has formulated a series of observations about the perspectives from which she came to writing. Her writings actively perform the work of philosophical reflection as it meets the thinker’s desire to write, forming identities (its own style and its writer’s self) while negotiating the running exchange between several inherited languages. Écriture in Cixous’ sense is a reflective act of becoming through formulating oneself in a language that integrates one’s knowledge of several languages or alternative environments. Thus, the resonance of écriture is helpful in this description of the way that I regard myself and many colleagues as developing a form of sonic writing ‘on the fly’, formulating individual works while acquainting ourselves with various contemporary and historical artistic traditions, and continually adapting compositional processes and methods to the technical needs and contextual norms of various sonic traditions.

A gender-dialectical dilemma

Equally importantly, ‘écriture’ evokes but stops short of specifying the (in Cixous’ writing, adjacent) adjective ‘féminine’, which is naturally a crucial coordinate in my attempt to situate my own practice within any artistic context.

Situating my work and artistic practice within a professional context is important for its ability to take place at all, to be nourished and sustained, received and remembered. For me, categorising my work as a composer entails an awareness of writing myself into a context. My ability to find and create contexts for my work that permit a personal economy on the level necessary for continuing to produce new work is also affected by the choice of professional environments and the collaborative opportunities that I perceive there.

My artistic practice involves positioning myself and my work within a matrix of creative and presentational environments, some of which are typified by social patterns defined by a history of masculine predominance. For this task of creating works within a partly ‘other’ environment, maintaining a productive sense of forming one’s own language from various traditions of inherited thinking in the tradition of an ècriture feminine is a powerful inspiration.

Cixous describes écriture féminine’ more in terms of what it does than what it is: “defining a feminine practice of writing is impossible within an impossibility that will continue; for this practice will never be able to be theorized, enclosed, coded, which does not mean it does not exist” (Blyth 2004: 18). In this, it displays a potential to circumvent and reformulate existing structures, which in turn opens up to the inclusion of other experience outside the body of concerns of a given theory. The practice of écriture féminine “takes place and will take place somewhere other than in the territories subordinated to philosophical-theoretical domination” (Blyth 2004: 18), engaging for example in a political and philosophical rejection of dialectical binary hierarchies such as culture/nature, technology/nature, writing/speaking, head/heart, colonizer/colonized, man/woman. Distancing myself from such dialectical hierarchies also seems more fruitful to me than emphasizing a feminine mode in contrast to the masculine mode within which my work is also implicated.

The point here is therefore not to set up an écriture féminine as a supporting binary to perceived patriarchal structures, but to plot a plausible motivation and reading of diversity and multivalency or the validity of alternatives within a work, context or environment. It is important to demand the appreciation of diversity and multivalency as artistic qualities, in order to challenge objections of banal eclecticism or perceived exoticism. Just as providing alternatives to universals, grand narratives and all-embracing categories is neither the domain of men nor of women solely or even predominantly but is an aesthetic project open to all and any, similarly the choice to work with multiple alternatives simultaneously, in opposition to ‘ontological integrity’ is available to one and all.

However, it has to be remarked that whenever a coincidence of financial and performance opportunities congregating around male composers is seen to persist (as it does within contemporary and computer music), coinciding with an aesthetic preference for ontological integrity within works or genres, the stage needs to be stormed by all manner of alternatives, including women. Narrative and identity are not independent of one another, and a diversity of both go hand in hand. To put it in concrete terms, it makes no sense to speak of post-feminism nor of a post-gender or gender-neutral approach within electroacoustic music (Ingleton, 2005) until the theorists, historians, gatekeepers, beneficiaries and main stakeholders are, for a sustained period, female in majority. This situation is also a motivating context for my work in seeking, formulating and integrating alternatives.

Finding and creating contexts

I have invoked an increase in the range of contexts as one of the benefits of integrating digital audio into composition for live and acoustic instruments and voices. Seeking and constructing contexts can occur at several levels within and around sonic works. Contexts of place arise through the use of field recordings from domestic, urban, suburban and rural environments. Media contexts arise through the use of audio downloaded or ripped from the internet – political speeches, for example, or iconic news reports, as well as technological engagement with the mechanisms of media and mass media, and the distribution of works through various media. Artistic contexts manifest themselves in concert, installation or other presentation forms; the kind of music or sonic art that venues present are influenced by the suitability of a venue’s acoustics or technical equipment, meaning that certain venues become in themselves a context for a certain type of music. Finally (or firstly, seen from the composer’s point of view), there is the context of a professional environment or milieu, with its attendant economies and structures, organisations and conventions.

Electroacoustic music was long considered to have originated necessarily in institutional environments for technological and academic research that were peopled by teams of engineers and utilized only the most high-end equipment of the given day. The opening of several studios in the mid 20th century followed this structure, such as Cologne’s Studio für elektronische Musik (opened in 1951), EMS in Stockholm (1964), STEIM in Amsterdam (1969) and IRCAM (1977). There was an assumption that the highest-quality equipment was also the most cutting-edge and relevant for creating electroacoustic music, and that such high-end, costly equipment was necessary for the future of (modernist) musical composition, requiring the calculation of complex systems literally beyond the capacity of the human mind. These qualities were also projected onto the theories and musical works that emerged from such environments.

Earlier electronic music inventions, preceding these studios, show that outside the institutional framework of publicly funded research, this was not necessarily the case. Electronic instruments such as the Hammond organ, theremin, ondes martenots and the electric guitar, all invented before the mid 1930s, have since made their way into a variety of musical genres, merging with various musical aesthetics and contexts.

Although much of the electroacoustic music theory emanating from the above-described studio research climates influenced composers’ behaviour with audio technology in the direction of an increased systematization and structuring of methodology and aesthetics. However, we can now observe that in the more recent ‘homegrown’ wave of individual artists using digital audio intuitively at personal workstations, a faster and lighter touch with technology has led to a fruitful proliferation of sonic materials working on multiple levels within works.

In a comparison of these two working practices within the field of contemporary music, we can generally say that electroacoustic music emerging from large institutional studios in research environments has typically evolved under pressure to legitimise the centres’ activities, staffing and finances in relation to the need to maintain and continually update equipment in the light of the forward motion of technological research, (Groth, 2010) while electronic music created using personal workstations evolves in a more anarchically free creative space where there are few aesthetic or financial responsibilities to be upheld. Thus, institutionally-grown electroacoustic music has evolved in a tight brace with its attendant technology and the necessity of such complex systems for a demonstrably complex music, while homemade electronic music arises from a lighter relation between user and technology, with artistic legitimation occurring more typically through social networking and online presence, and through performing music in contexts beyond the frame of the contemporary music concert.

It would not be accurate to say that the first approach is more intellectual or academic than the second, as is often claimed, but it may be the case that the second approach has had a dispersing effect on the stringencies of contemporary music, leading to the development of compositional and listening strategies that are more varied and may work more explicitly at incorporating an awareness of context on a number of levels.

Digital écriture in my practice

At this point, it is relevant to give an overview of my use of digital audio. The thrust of my work in this area has gone into merging live acoustic events with recorded, amplified or processed sounds on a relatively equal level. Never having created work in a large studio, the scope of technology used has been limited to the range within personal investment - of time (learning new software and hardware instruments) and of money - supplemented by the ad hoc hiring of assistance for sound design, mastering, programming and diffusion. Concentrated on recording, editing, microphones and diffusion, my practice has not (yet) ventured into more technologically advanced endeavours such as interactive installations, algorithmic composition, programming, live coding or data sonification.

Coming from a background in acoustic chamber music, I made my first studio production in 2002 (Maps the CD, with David Young and Cynthia Troup, 2002) and in 2003 I began working with a digital audio workstation (ProTools) for editing sound material. I started by editing material that I had recorded for specific concert and music theatre projects (A Quarreling Pair development (2003), I Greet You A Thousand Times (2005), Scrape (2010), All my friends really are superheroes (2011), La Coquille et le Clergyman (2012), Allerleirauh (2012)).

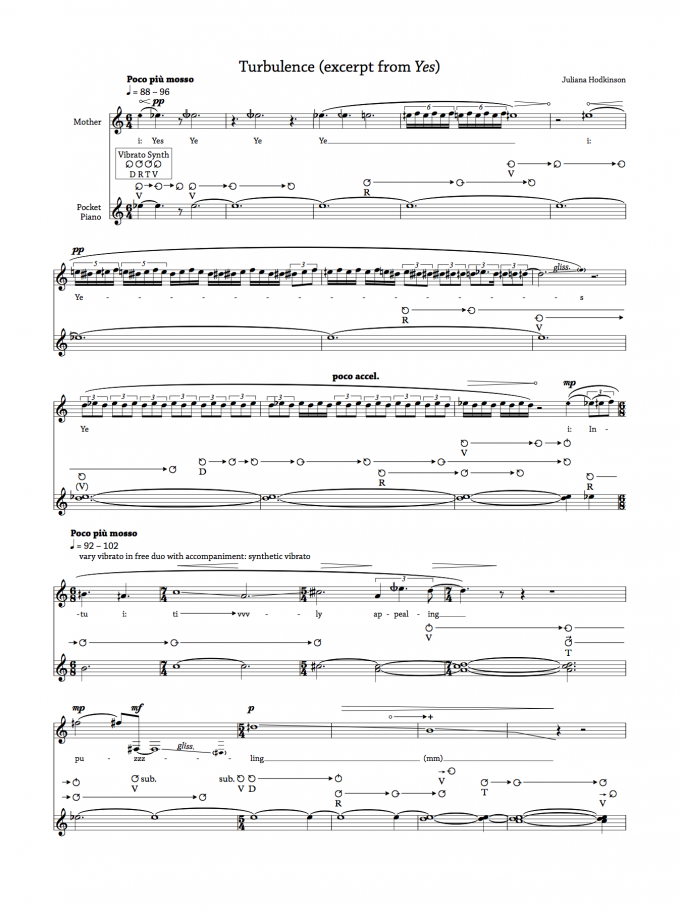

Recording then took me beyond the studio framework, as I started making urban, rural and domestic field recordings (The General Case, with Jennifer Walshe, (2007), We’d just got back from outer space, when there was a knock at the kitchen door (2008), When the wind blows (2009), Fahren, fahren, fahren … (2011)), while also blogging about field recordings and urban sounds. Having worked with sound-effect libraries (Ikke et hjem, 2007), I also began taking sounds from the internet, using freesound and other free audio download sites (Versprengung (2010), Play (2010), Prompt, immediate, now / very restrained and cautious (2013), Defending territory in a networked world (2013), Third-Millennium Heart (2013)). In 2011, I began using a digital sampler (Roland SP 404) for performing my own ‘live soundtracks’ to experimental films (Fish & Fowl, with Niels Rønsholdt, 2011, La Coquille et le Clergyman, 2012, Allerleirauh, 2012), and in 2013, I added a mini electronic circuit-bending synthesizer (Third-Millennium Heart, Turbulence, Ten Minutes Older, all 2013).

The terms ‘writing’ and ‘écriture’ imply that authorship and writing are embodied in the same person; that connotation must in this case be nuanced by pointing out that the production of my works is sometimes (under ideal conditions) a team process involving copyists and sound designers. This may be true for many composers’ work today, but still the contribution of various fields of expertise to the resultant writing is often suppressed by construing the contemporary compositional process as being crafted by one pair of hands. The trope of the composer as sole author of musical works has survived many anecdotes of large works facilitated or completed by assistants and protégés, and may be partly responsible for the considerable amount of time devoted to technical and technological training in composers’ education, partly at the expense of advancing and updating aesthetic standpoints or of opening up to diverse contexts and influences.

In my electroacoustic works, I often gather samples according to pre-decided conceptual thematics, which I then break down into sonic material with a musical viability within my instrumental language. At the same time, I explore a more abstract trajectory from the work’s original thematics to instrumental writing, converting what is literal and actual (representational and referential) to metaphorical tools for instrumental composition, such as ‘thousand’, ‘turbulence’, ‘dissolve’ and ‘touch’. I then drop various complementary instrumental sections around the samples, testing each for effects of contrast/homogeneity. As the musical composition progresses, the instrumental weave becomes the sustaining texture, with samples then being edited and processed around the instrumental music in order to ‘fit’ it. With recent works’ addition of sung and spoken voice, augmented electronically, a new melodic language has started to take shape, animating the middle register of my writing (the range of speech) with a more inflectional character.

There is a discrepancy between the origins and pace of development of these disparate materials: instrumental music can be written even when no recordings have been made and no samples have been chosen, and thus it may be possible to start or continue writing some instrumental passages before the editing and mastering work is done. On the other hand, the technical writing of instrumental parts and scores can be extremely time-consuming. The two working processes often progress out of sync with one another, while constantly cross-feeding. This is at times frustrating, but also liberates each process from its respective concern with speed/deliberacy, as they rely on different time principles. For example, there is a tendency to notate everything in MM 60 when there are samples whose duration in seconds will of course be the measure of much of the rehearsal communication during sound-design, pre- and post-production. To subvert this with notating the instrumental parts at a pulse of 56 or 63 is at times to invite approximation (a little bit slower or faster than seconds’ pulse) and at times necessitates complicated and possibly musically counter-intuitive mathematics that tend in practice to yield before simpler ratios.

Proliferating contexts and relational matrices

“Borders between different worlds do not have to be erased; different spaces do not have to be matched in perspective, scale, and lighting; individual layers can retain their separate identities rather than being merged into a single space; different worlds can clash semantically rather than form a single universe.” (Manovich 2001, p. 148).

New media theorist Lev Manovich’s evaluation of the legacy of editing and montage in 20th century cinema also applies to the opportunities for multi-layered textures offered by multi-track digital editing, and correspondingly to the expanded potential for creating sonic collages that evoke a sense of diversity and multi-valency. Although collage and extreme contrast are equally achievable within purely acoustic music, they cannot reliably refer beyond the frame of the concert except historically.

This state of affairs explains the opening towards contexts beyond the concert hall that took place when I began to use sampling. The semantic clash described by Manovich was my formative experience while working on the orchestral video concert I Greet You A Thousand Times. This work uses recordings of Brahms’ First Symphony, notated and specially recorded permutations thereof, ambient mountain soundscapes (a hyperromantic sound collage constructed from field recordings) and audience applause, all cued as samples within an orchestral concert, with video images by visual artist Joachim Koester projected above the orchestra. Collaborating with Koester from the start in search of a viable performance format for video and orchestral music, we set up a series of binary contrasts (such as live orchestra – recorded orchestra; Brahms forwards – Brahms backwards; speeded up – slowed down). Once these operations established themselves within the work, the space between them became an expanded field of relational matrices for comparing and contrasting a contemporary orchestra with its typically historical repertoire, and for viewing both history and the present together in such a way that neither conclusively had the final word.

Taking the final three words from the much-cited musical relic of Brahms’ postcard to Clara Schumann – a sketch of the finale’s horn melody - as our point of departure, Koester and I used their connotations of repetition and multiplication both as an indication of the repetitive and reproductive recording and performance industry that has grown up around symphonic music, and also as a concrete instruction for compositional manoeuvres, such as imagining Brahms’ 1st Symphony played at 1000 times its usual range of speeds, repeated a thousandfold, or cut up into a thousand pieces. Such an iconic repertoire work tolerated this relatively brutal treatment by virtue of its strong timbral and motivic identity, and due to its being lodged unmovably in social memory.

Contextualising Brahms’ symphony in these ways – relating it visually to its home in the symphonic hall and to Alpine landscapes and linking it sonically to cow-bells, mountain goats, audience applause, rehearsal sounds and studio recordings – offered a view of a work of ‘absolute music’ as being connected through design and resonance to outdoor landscapes, to its audiences’ reception history, to its orchestras’ daily practice and to the recording industry by which orchestras have survived into the 21st century, as well as to the composer’s personal journey.

The term ‘relational matrices’ is borrowed from Erin Manning’s account of how the performative turn in the humanities, based on studies of bodies as social phenomena, has been empowering for the acknowledgement of all kinds of interdisciplinary interaction, collaboration and correspondence, and of social identities in flux (Manning, 2007). In my practice, Manning’s account of how bodies interact, and how they change through interaction, is inspiring for the project of engaging both with entities as apparently fixed as historical symphonies and also with evolving artistic practices.

Manning’s politics of touch views bodies in interaction, ‘touching’, engendering individuation, where “to engender is to undertake a reworking of form”. She invokes a progressive, fluctuating mode of seeing disciplines and their frameworks and borders – a mode that also applies in collaboration between artists, whether they be two composers or, for example, a composer and a visual artist. With touch, Manning introduces the skin as a surface in constant integration (wounds growing over) and disintegration (flaking), appearance (growing) and disappearance (growing old, from day to day, shedding skin cells in order to let a rejuvenated layer come to the surface where it will touch and be touched). Integration and disintegration, appearance and disappearance are also ways of regarding the contact between disciplines, between artists, between contexts evoked through sound, between artworks undergoing versionisation, during a composition process.

Manning’s focus on engendering turns on the undertaking of a reworking of form, potentializing matter. Composing is normally the opposite of this, it objectivizes potential, makes material manifest, fixing it, finding its eventual form, an ultimate objectification in the form (traditionally) of the score, or of the unique performance or final edit. The engendering metaphor is very motivating for the idea of reworking, of seeing not only material but even a finished work as having a potential which persists, such that every new fixing points to its next potential undoing. This keeps the door open to new contexts and diverse influences.

Gender and technology

Where the influences on my instrumental writing by writers such as Hélène Cixous, Gilles Deleuze & Félix Guattari, Erin Manning and Elizabeth Grosz must necessarily remain obscure to anyone but myself, the resonance of my work with notions of writing as a practice, and of becoming, touch and vibration might occur without further mediation to a reflective listener. Emerging from a background entrenched in canons of works whose interpretation turns on details of phrasing, tempi and vibrato, into the paradigm of electronic music in which any recordable sound may be combined with any other(s), it has been imperative to acknowledge processual fluidity of every kind and the productivity of maintaining spasms between various mutually exclusive states as possible expressive goals.

Much of the discourse within advanced gender studies centres around the body, leaning on performativity theories that influence a shift from text and all fixed forms towards the prioritization of all that is sensual and perceptual - body, space, light, sound, pitch, etc. Although it is not obvious how to push off from the micropolitics of body-centred gender studies to an account of creativity in the technology-focused digital realm, my point is precisely that the fluidity of digital working processes enables this. I briefly trace a course of development in my practice, from scenarios that explicitly locate music in the body to the electronic extension of body and voice, resulting in explorations into the meeting of natural and synthetic vibrato in an unresolved muscular and artistic spasm.

I have worked explicitly with body-related sounds in In slow movement (1994) (using breathing as the coordinating instance for chamber music in a mid-size ensemble); What happens when (1999) (thematising female self-articulation in song); Third-Millennium Heart (2013) (using a fetal heartbeat as sample); When the wind blows (2009) (in which children’s toys are integrated as musical material on the same level as Webern’s Variation I for piano, op. 27); PLAY (2010) (sounds from various typically boys’ games as sampled material for a brass trio); and Turbulence (2013) (based on a libretto by Cynthia Troup that focuses on a mother-daughter relationship, vocally staging female self-articulation through birth and song as ambiguously related).

Working with electronics has enabled me to escape some of contemporary music’s reluctance to deal with the human voice. In Rückspiegel: eine Hörsituation (2011) and Versprengung (2011), an amplified male baritone voice is supported with pitch-shifts extending the bottom range of the voice, so that a series of downward glissandi seem to end in an unusually dramatic expression, ‘crash-landing’ below the vocal register. Combined with a light distortion, the male voice takes on additional power and monstrosity, gaining something of the excessive and over-emotional hysteric expression so often attributed to the upper female range in western vocal traditions.

Vibration

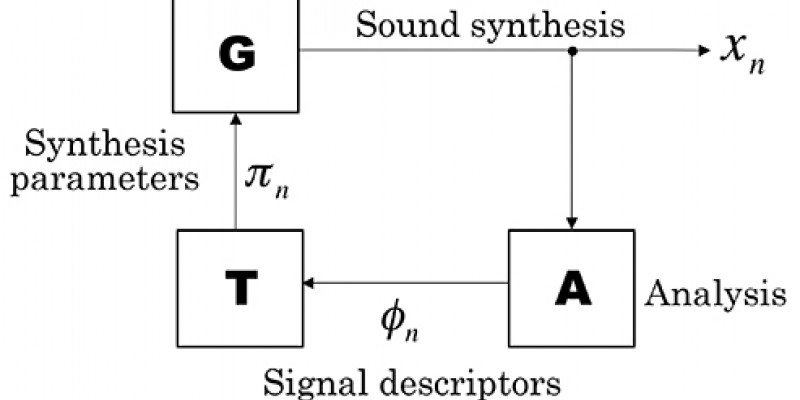

In Turbulence (2013), a soprano voice is supported by an electronic circuit-bending synthesizer that produces a synthetic vibrato of manually variable amplitude and rate. Although this exaggeration of a musical archetype (the soprano with excessive stylized vibrato) points towards excess and emotionality, the control with which the soprano locks her trained vibrato to the machine’s variable ‘behaviour’ demonstrates a distanced and cerebral approach to adapting the oscillation of vocal chords to a low-frequency oscillation. Due to the proliferation of permutations once several filters on the synthesizer begin to interact, it however sounds as though the machine is apparently losing control over the rate and amplitude of its oscillations, with glissandi becoming ever more wild, and harmonizing bends and slides interrupting the smooth curve of the regularly oscillating pitch.

I attach great importance to the topic of song as something both natural and intuitive, and as highly constructed or stylised. The ambivalence of contemporary and computer music to deal with an aspect of music that is for many the only and most intuitive route to music-making has also problematized these two musical genres’ practice as performing, live and digital art in search of a performative mode. I proceed to elucidate some possible relations of synthetic and natural vibrato, in dialogue with Elizabeth Grosz’s Darwinist account of the role of vibration in sexual selection.

“I hope to understand music as a becoming, the becoming-other of cosmic chaotic forces that link the lived, sexually specific body to the forces of the earth.” (Grosz 2008: 26)

In contradistinction to the cerebral approach to music that has long typified contemporary music as a professional milieu, Grosz regards, with Charles Darwin, music as being the “most seductive of the arts, the one that most immediately enhances a sense of well-being, the art that most directly enchants (or equally infuriates)” (Grosz 2008: 26). Having a special role in sexual selection, which in turn aids - but is in excess of - natural selection, music’s vibration, for example, “and its resonating effects on material bodies … generates pleasure, a kind of immediate bodily satisfaction. … Rhythm, vibration, resonance, is enjoyable and intensifying” (Grosz 2008: 32).

Although this romanticising view of music is hard to swallow when met in the context of contemporary music, it provides the ‘natural’ and bodily foundation for an ensuing softening of evolutionary narratives. Grosz introduces vibration as a description of ambivalent oscillation between not only any two bodies, but also, more metaphorically, between any two states. In my present practice, vibration can serve as a working musical and technical metaphor for the attempt to bridge notated music and digital audio. This account of vibration, together with Manning’s account of touch, provides a plausible mode of pursuing different artistic goals with various means simultaneously.

Commonly eliminated from contemporary instrumental music with the indication senza vibrato, vibration is typically associated with an augmentation of expressivity in vocal and instrumental music, particularly in the upper melodic register. A regular, pulsating change of pitch centred around a main homing pitch, it may be varied in amplitude or speed.

“Living beings are vibratory beings; vibration is their mode of differentiation, the way they enhance and enjoy the forces of the earth itself.”

As for Deleuze & Guattari, birdsong is crucial to consider in this line of reasoning. One question considered at length by Grosz, with Darwin – namely, whether music or language evolved first, and to what extent there are parallels between birdsong and human song - is relevant for my reflections on the dynamics of processes involving two or more fields. Concluding that various animals’ musicality evolved ‘convergently’ (instead of in a linear chain of causal development) permits an evolutional dynamic that is more like a collective swarm of parallel developments than a single-track one-way development leading from pre-developed to post-developed, and therefore having an end.

Jakob von Uexküll is invoked in this debate to weigh up the relation between the individual animal’s musicality and the grander scheme of its milieu and its ‘lifeworld’, which are both somewhat different to Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of ‘territory’. Grosz draws the comparison with an individual instrument in an orchestra.

“The organism is equipped by its organs to play precisely the tune its milieu has composed for it, like an instrument playing in a larger orchestra. Each living thing, including the human, is a melodic line of development, a movement of counterpoint, in a symphony composed of larger and more complex movements provided by its objects, the qualities that its world illuminates or sounds off for it. Both the organism and its Umwelt taken together are the units of survival. Each organism is a musician completely taken over by its tune, an instrument, ironically, only of a larger performance in which it is only one role, one voice or melody.” (Grosz, p. 43)

This image of the musician being “taken over by its tune” supports my earlier proposal that sounds compose works at least as much as composers compose works with sounds. Or: tunes write their musicians, during larger performances within proliferating contexts, in which the individual cells and participants are but a part.

Conclusion

Formulating my work with, and within, various contexts as a contrapuntal movement involving larger and more complex dynamics, allows the touch of technology to sit lightly on my work, supporting multivalency and broadening contexts from limited signifying economies to situations and contexts characterised by plurality. Works devised in this way enable me to socially contextualise my work more convincingly than is possible when continuing to work exclusively within an acoustic concert paradigm.

Urban traffic, birdsong in the countryside, domestic sounds, toys, radio, synthetic or heavily processed sounds, re-appropriated samples from news media, material provided by audio communities such as freesound.org, etc., films, classical repertoire – all may enter electronic works as content, expanding the individual work’s context. My writing for instruments has usually been characterised by a tendency towards reduction – a productively intended lack of sound, of instrumental virtuosity, of expected outcomes. This stands in stark contrast to the apparent excess of so many contents entering through recording and editing and may explain the appeal of turning away from essentialism in terms of the autonomy of concert music and its possible ontologies.

Trawling through centuries and continents of socio-cultural values to be re-considered and re-arranged in new relations to one another, my search for diverse sonic materials has taken me on extended walks (field recordings) and long surfs (downloading or ripping audio from the internet), venturing ever further afield from the composition desk. Once the recordings are ‘in the bag’, the process of editing them into samples and collages closes me off from the world as I sit with headphones and a laptop creating connections between the recordings’ original forms and the imaginary constructions that arise from bringing them together with acoustic musical writing for instruments. As I begin to collect the sounds into a score with connected samples and technical plans, the sounds take over my writing while I write myself and my practice into new sonic contexts.