»Music to me is – having spent a lot of time listening, composing, and thinking about it – still, essentially, a mystery.«

Polish-born Szymon Gąsiorek has done it again – created a cornucopia of an album that both overwhelms and delights with its endless wealth of eclectic ideas, styles, and sound sources. As is often the case with this kind of release, where each track has its own distinct identity, personal favorites quickly emerge.

One clear favorite announces itself right away. The opening track, »TAK TAK NIE NIE«, explodes with an energy reminiscent of early Boredoms – a heavy dose of noise rock with shouted vocals, electric guitar, saxophone, gunshots, screams, synths, piano, and more. The third track, »STRACH LĘK NIEPOKÓJ«, also shines with a zeuhl-like momentum driven by militaristic vocals, insistent drums, jagged guitar, and saxophone. And even beyond the most immediately impressive tracks, Polofuturyzm is so packed with highlights and playful surprises that even half of it would have sufficed. Take, for example, »90s [NADZIEJA]«, featuring a trancey synth quickly and effectively sabotaged by free jazz-style drums and saxophone, or »JEDNOKIERUNKOWY«, which sounds like classic disco polo thrown in a blender and mixed with pitch-shifted vocals and clubby keyboards. Not to forget the eight-second slapstick piano flourish on »RĘCE«.

Polofuturyzm is driven by a manic refusal to ever look back. The only constant is the absence of consistency. Gąsiorek has been here before, but it still feels just as radical and refreshing.

English translation: Andreo Michaelo Mielczarek

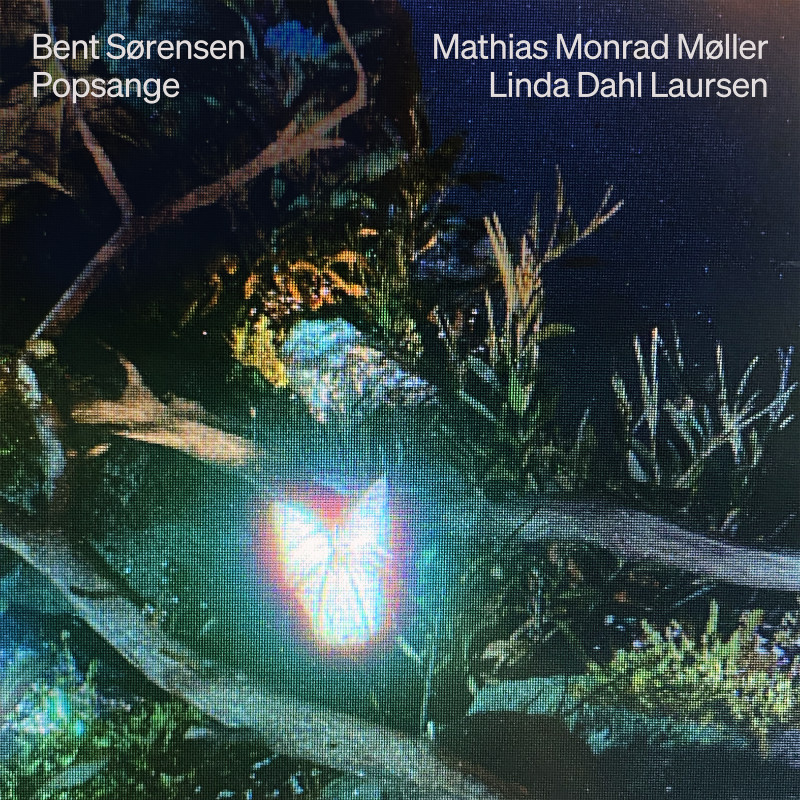

»Your eyes are in reality luminous tunnels to another reality.« So goes one of the key lines in the opening song of Bent Sørensen’s song cycle Popsange, inspired by texts by Michael Strunge. It sets the tone and points toward the recurring lyrical themes: all-consuming love, the shared journey toward another place – and the eyes, always the eyes, appearing in almost every single song.

Mathias Monrad Møller sings with great sensitivity, bringing the text to life, and his interplay with Linda Dahl Laursen is strong. Yet Popsange has much more in common with lieder than with actual songs – not least because of the text’s at times highly poetic language. The tender, almost naïve voice of the lyrics receives its most convincing counterpoint from the piano, as in »Illusion«, where it first follows and supports the words, only to break out into rapid, dissonant chords that interrupt and almost mock the singer.

Still, traces of pop music can be found here and there. »Tid og rum« builds on repetitions with small variations, much like the verses of a pop song. And in »Hjertestrøm«, Møller colors his voice with a timbre that could easily fit on a pop album – not least because the piano here is delicate and playful, giving the voice more freedom.

All in all, Popsange is a pleasant listening experience, but I miss the presence of David Bowie and Lou Reed on the musical front. The work is at its most innovative where it dares to embrace pop. Imagine if the texts had been carried by actual verses, hooks, and choruses – elements that might have turned them into true earworms.

English translation: Andreo Michaelo Mielczarek

On Kaikō – the trio Treen’s second release – saxophonist Amalie Dahl, pianist Gintė Preisaitė, and percussionist Jan Philipp demonstrate confidence, mutual trust, and a distinct musical adventurousness. The opening track »Hylē« unfolds with rattling percussion and strikes seemingly aimed directly at the piano strings, stumbling forward over an underlying drone. The saxophone cuts in with phrases that sound at once admonishing and bewildered. Nothing feels meticulously calculated; instead, the music is carried by a keen awareness of the three musicians’ individual voices within the shared soundscape.

The same basic formula unfolds across the album’s three other pieces, yet always in new variations. On »Kinetic«, Dahl’s saxophone emerges with much greater weight, its slowly growing crescendo mirrored and challenged by Preisaitė’s piano. Improvised music can often slip into polite holding patterns, with the musicians taking turns in the spotlight – but not here. Dahl, Preisaitė, and Philipp appear as three drifting islands without anchors, propelled by their own currents yet inexorably drawn in the same direction. The result is both sudden shifts and an organic flow that can pull the listener into a trance, if one surrenders and simply lets the sound wash over.

It is precisely the trust between them that allows the three to play freely, without fear of leaving or losing each other. In doing so, they create a momentum that is hard to resist – whether one chooses to let the islands drift past or to float along in their current.

English translation: Andreo Michaelo Mielczarek

The first time I heard the title of this opera, I was reminded of Franz Kafka’s grotesque short story In the Penal Colony (1914–19), in which a prisoner is sentenced to have his punishment – a moral admonition – engraved into his skin, after which he is meant to feel what it says. In Written on Skin, which premiered in 2012 and has quickly become something of a modern classic in opera houses around the world, the writing on the skin is instead the caress of a young illustrator, who in reality (!) is an angel. The story is set in the 13th century and appeared in Boccaccio’s collective narrative The Decameron in the following century, but it could just as well take place in a dystopian future.

In a land ravaged by war, violence, and terror, the illustrator is hired to create a book for a tyrannical and ultra-violent lord who, among other things, regards his wife’s body as his own private property. The illustrator/angel, however, enters into a passionate relationship with this wife, and all hell breaks loose. Naturally, they both die, and the lord is left alone with his bitter, useless victory, while the angel is resurrected and thus becomes the true victor – and perhaps a queer figure, as the voice type (countertenor) might suggest.

The Royal Danish Theatre’s production is highly convincing. Benjamin’s music roars and crashes, yet is at the same time curiously hushed in its markedly economical use of means. It is as hard as steel forks magically bent again and again, while the often very powerful volume inscribes itself onto the skin of the eardrums in silken script.

English translation: Andreo Michaelo Mielczarek

»Music to me is – having spent a lot of time listening, composing, and thinking about it – still, essentially, a mystery.«

»Music for me is a universal tool for opening myself for feelings. It may be anger. It may be happiness or sadness. Music may make you wanna dance or cry. But it never leaves you indifferent to the emotional load it brings. Good music, at least. Music may tell stories. It may as well be a background, or a soundtrack for the moment, for the day, for life. That being said, music for me is a company for everyday. And I’m quite lucky that it’s my company at work as well, I guess.«

Jan Janczy is a Polish journalist and radio host at Radio Nowy Świat. His main fields of professional interest are Northern Europe, international affairs and music. He interviewed among others 3x Grammy Awards winner Fantastic Negrito, Röyksopp, Alabaster DePlume, Archive, Trentemøller and Mogwai. In 2024 together with JazzDanmark, Kultur(a) and Radio Nowy Świat he released a podcast series devoted to the history of Polish-Danish jazz connections. He is a Swedish philologist by education.