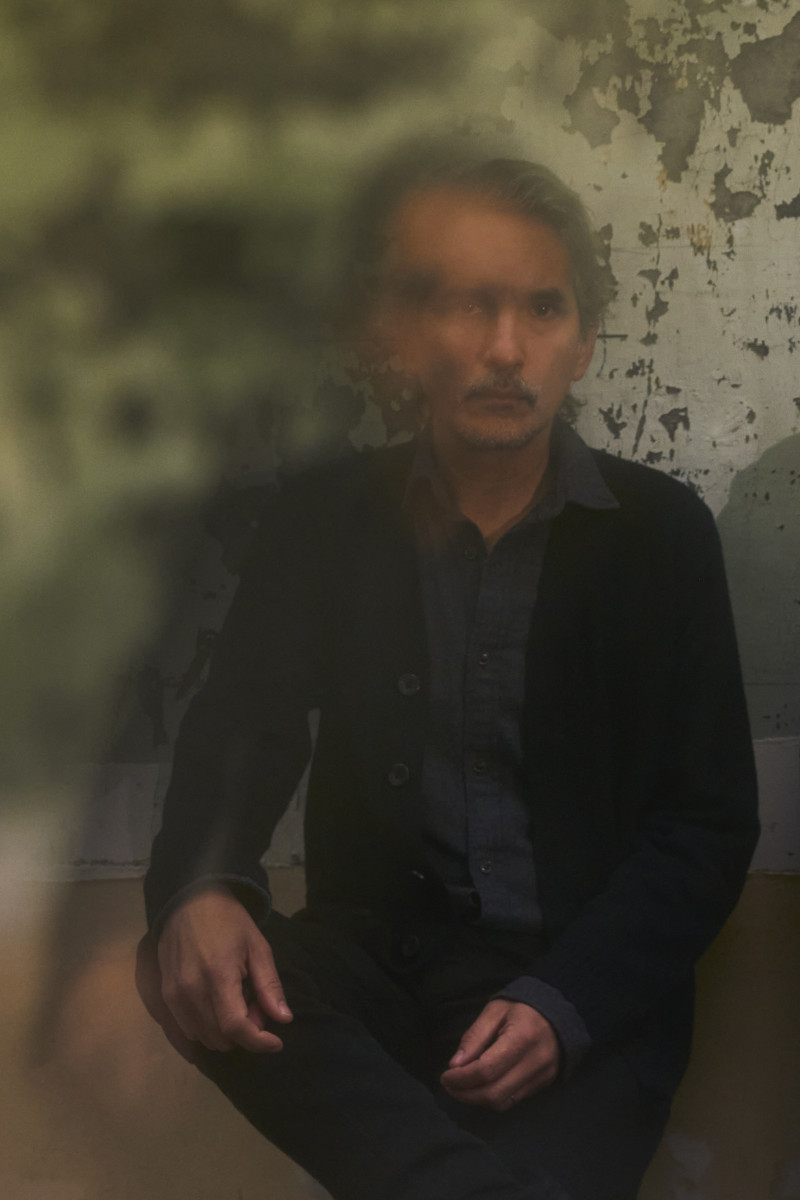

We sat in slow decay for an evening in the vestibule of Hell. It was during an ambitious, multisensory interpretation of Charles Baudelaire’s poetry collection Les Fleurs du mal (1857) – Helvedesblomsterne (The Flowers of Evil). Director Anna Schulin-Zeuthen and composer Mikkel B. Grevsen brought together mezzo-soprano Sophie Haagen and actor Thure Lindhardt with the six string players of Ensemble Hermes, adding electronic music to the mix. This Frankenstein-like staging transported modernist poetry into 2026, where the motifs stretching between beauty and decay still – despite many scientific advances – remain a fundamental condition.

In Musikhuset Aarhus, the stage was decorated with lush and withered flowers as vanitas symbols. Lindhardt opened with a recitation that shattered the fourth wall: with both humour and intensity he addressed us directly in the audience – hypocrites and future corpses.

In contrast to the almost seamless sonic unity of Haagen’s dark voice, the string players’ sustained textures and the ghostly distortions of the electronics, Lindhardt’s reading appeared as a strange but necessary disturbance. He prowled about with a folder tucked under his arm like an awkward outsider – the poet as eternal observer.

For my part, I dutifully tried to follow the printed programme sheet, but soon gave up and instead – quite in the spirit of the work – allowed myself, hypocritically, to be intoxicated and seduced. Helvedesblomsterne succeeds as a bold and grand project. Yet the performance also balances a little too cautiously between harmonic beauty and the nineteenth-century uncanniness that in Baudelaire crawls with death all the way into the bones.

English translation: Andreo Michaelo Mielczarek