... too wide a field. Sound Art in Berlin.

After the defeat of fascism in 1945, the victors - Russia and its three Western allies, America, France & Britain – split Germany into East and West, separately dividing the former Reich’s capital, Berlin, turning the Western part of Berlin into an enclave surrounded by the new East German state - the German Democratic Republic.

The following fortification of this division by the erection of the Berlin Wall in 1961, the sectors forming West Berlin could only be reached from the rest of the Bundesrepublik by travelling through designated, and well- guarded transits, by road, rail or air. So everything – people and goods – had to be “imported”. (The Soviet blockade of 1948/49 showed how easily these lifelines could be disrupted). And although West Berlin was not the capital of West Germany – which was now Bonn – special efforts were made to turn the city into an attractive and flourishing place – not least to act as an advertisement aimed at the Eastern Block for the superiority of the Western lifestyle. This situation affected not only living conditions, but also the city’s art and culture.

In 1963 the American Ford Foundation initiated an artists’ residency programme, which was adopted two years later by the now legendary German Academic Exchange Service – or DAAD –as its Artists-in-Berlin Programme (Berliner Künstlerprogramm). Supported by the German Federal Foreign Office and the Senate of Berlin “the program annually invites around 20 artists working within visual arts, literature, music and film to spend a year [or six months – kg] living and working in Berlin.”[i] By bringing many international artists into the city, this programme kick-started the development of the arts in West Berlin after the war. The list of musicians, composers and artists invited, reads like the Who’s Who of their genres – from Igor Stravinsky, John Cage, Iannis Xenakis and La Monte Young to Alvin Lucier, Bill Fontana, Akio Suzuki and Max Neuhaus.

It was through these visiting international artists – many of whom extended their stay in Berlin long beyond their DAAD-residence period – and the close ties that existed between West-Germany and its allied states that by the early 1970s an interesting experimental art field had begun to form in West-Berlin. This made it a magnet for West German artists in general. Particularly the younger ones, since residents of West-Berlin were exempted from the obligations of military service.

SoundArt Beginnings

In the experimental and often cross-generic art practices that were then emerging, sound other than music began to play a role. Several artists already involved with sound objects, installations and performances with roots mostly in the visual arts were already living in Berlin – like Rolf Julius, Martin Riches and Rolf Langebartels[ii], and their activities were variously supported by the Academy of Arts, the Künstlerhaus Bethanien, and the DAAD Artists-in-Berlin Programme.

In 1978, Rolf Langebartels opened a small independent gallery in a quiet residential street in Berlin-Charlottenburg – the Gallery Giannozzo. Site of the former Gallery Giannozzo, 2014. First concerned with photography and visual arts it soon – inspired by the open-minded, experimental, Fluxus-fueled atmosphere of the time – widened its interest to include sound, becoming the first SoundArt gallery in the city. Amongst the earliest artists to exhibit here was Rolf Julius who, in 1980, showed Body Horizon (Portrait of N.)[iii] –a series of close-up body shots accompanied by quiet taped sounds. Langebartels’ gallery was focused on hybrid art works and events, which often included a sound component, and collaborated with artists and theorists who came from a wide range of disciplines – as well as publishing texts and cassette-recordings linked to his exhibitions and events. In the 1980s the Gallery Giannozzo became in the 80’s an important meeting place in which artists working with sound could gather and experiment.[iv]

Site of the former Gallery Giannozzo, 2014. First concerned with photography and visual arts it soon – inspired by the open-minded, experimental, Fluxus-fueled atmosphere of the time – widened its interest to include sound, becoming the first SoundArt gallery in the city. Amongst the earliest artists to exhibit here was Rolf Julius who, in 1980, showed Body Horizon (Portrait of N.)[iii] –a series of close-up body shots accompanied by quiet taped sounds. Langebartels’ gallery was focused on hybrid art works and events, which often included a sound component, and collaborated with artists and theorists who came from a wide range of disciplines – as well as publishing texts and cassette-recordings linked to his exhibitions and events. In the 1980s the Gallery Giannozzo became in the 80’s an important meeting place in which artists working with sound could gather and experiment.[iv]

As these home-grown activities began to spread, an interesting injection of new ideas was on its way. In 1980, curator René Block together with Nele Hertling from the Academy of Arts West Berlin organised an exhibition in the Academy building focusing on cross-genre practices between the visual arts and music. They called it For Eyes and Ears – From musical clock to acoustic environment[v] and it featured sound objects, installations and performances. Drawing on Futurism, Duchamp and Fluxus, and using Block’s contacts to the New York art scene, they presented sound works from American artists, like George Brecht, Harry Bertoia, Alan Kaprow, Laurie Anderson and Bill Viola, and Western Europeans, including, Jean Tingely, Jannis Konellis and the Baschet Brothers with their Sculpture Sonores). 138 mechanical and electronic instruments were exhibited, as well as sound objects and acoustic environments - and there were also performances, concerts and workshops.

It was through this festival that the extent and hybridity of the SoundArt field became clear, only amplified by the substantial overview catalogue, which gave for the first time, to my knowledge, a comprehensive account of both the historical background and the current extent of cross-genre activities in both Art and Music. This exhibition had an enormous influence on SoundArt activities in Berlin West.

Inspired by the festival and its catalogue, Ursula Block founded Gelbe Musik (Yellow Music) in 1981, a small record store located in West Berlin that specialised in experimental music and sound works, sometimes also hosting small exhibitions and performances. It closed this spring, after 33 years of continuous existence.[vi]

Then, in 1983, Freunde Guter Musik Berlin e.V. was founded “as a non-profit association dedicated to presenting and promoting new music and music in new forms.”[vii] All through the 1980s and ‘90s, they brought concerts of unconventional experimental music to Berlin, showcasing the new international Improv scene and various hybrid musical forms allied to dance, projection, new media various kinds of performance art and occasionally SoundArt.[viii] These programmes impacted considerably on the music and sound art culture of Berlin, particularly in the years after the fall of the Berlin wall.

More established fields of music also began to expand in the 1980s - and in 1982 the Inventionen festival was inaugurated as a collaboration between the DAAD and the Electronic Studio of the Technical University Berlin West. It was dedicated mainly to Electronic, Electroacoustic and New Music, but in time began to include sound installations and sculpture, reaching a peak around the new millennium, when SoundArt itself was in full flood.

At the same time, the TU Studio – which had been operating continuously since the1950’s, opened up its technical facilities to SoundArt artists. Firmly rooted in Electronic Music, it had first expanded to include Minimal music and Fluxus activities, making “another wind blow from America over the Wall into West-Berlin”[ix], as Folkmar Hein, the head of the studio reflected. By 1985 the studio was producing SoundArt works too on a regular basis,[x] with particular focus on sound spatialisation and the development of space-sound operation systems. It also established a weekly forum in which composers and SoundArt artists met to exchange ideas about their work: EMhören (ab 1985).

Another indicator of the growing awareness of SoundArt in Berlin West was the realisation in1984 of its first permanent Sound Installation by the Viennese architect Berhard Leitner. His Ton-Raum was one of three prize-winning projects submitted to an art-in-architecture competition set up by the Technical University’s Building Department. Installed in a corridor-intersection in the main building of the university, after 30 years of existence, Leitner’s Ton-Raum is still today running, and still as intriguing as ever.

The constant influx of international musicians and SoundArt-artist coming to Berlin through the support of the DAAD made an immense contribution to the cultural life of the city. Apart from providing space and a reasonable stipend, the DAAD also organised forums in which their artists could show their work, and found suitable opportunities for them to collaborate with local artists. For that purpose the DAAD ran its own gallery and supported SoundArt publications in collaboration with, amongst others, Kehrer Verlag. A good example of the success of the DAAD’s Artists-in Berlin programme was Bill Fontana’s 1984 sound translocation Distant Trains, Berlin’s first public space sound installations, realised on the site of the former train station – the Anhalter Bahnhof. Ruin of the former Anhalter Bahnhof

Ruin of the former Anhalter Bahnhof

Berlin East

While all these activities were going on in the Western part of the city, the Eastern part, so far as SoundArt was concerned, remained pretty quiet. As the capital of the German Democratic Republic (GDR), Berlin East also enjoyed special status. Due to the official centralised politics and its close proximity to West Berlin, the city was financially and culturally favoured and attracted many artists and musicians. But in the East, regional cities like Leipzig and Dresden, had marginally better opportunities to pursue alternative and underground activities since they were able more easily to operate beneath the official radar.

Cross-genre experimentation in the East was mainly pursued in the fields of Jazz, Improvisation[xi] and contemporary composed music[xii]. There was a tentative link between art and music in form of music performances in galleries and collaborations between musicians and artists (Georg Katzer and Dieter Tucholke). Fine Kwiatkowski’s work might stand here as an example of the crossover activities in Performance and Dance. A dance improviser, she collaborated extensively with improvising musicians, contemporary composers, visual artists, filmmakers and theatre performers.[xiii]

Song theatres groups, such as SCHICHT and Karl’s Enkel also experimented in the grey zone between music and theatre. Major festivals, such as the Leipzig Jazz Days, the Music Biennial Berlin and The Political Song Festival made it possible to invite musicians and composers from the West into what otherwise was a quite isolated and sequestered environment –in those times all contacts to the West had either to be officially sanctioned or arranged unofficially on an individual, and therefore semi-illegal, basis.

Between 1984 and 1988, I organised the concert series Music & Politics under the cloak of East Berlin’s Political Song Festival. It was presented in Brecht’s Berliner Ensemble, and brought Avantgarde-Rock groups and other Western experimental music to the East. It experimented with mixing different musical genres in the space of a single concert – something still unusual in the early 1980s.

Cultural isolation from the West became increasingly unsustainable during the 1980s and contributed to the fall of the Wall and the reunification of the two Germanys.

Post-Wall

When the wall came down in 1989, the cultural situations in the very different parts of Berlin ground up against one another and it took a while – almost 20 years – for them to grow together.

While West Berlin brought a considerable SoundArt awareness to the table, East Berlin contributed something very different, but vital for the form’s advancement, namely, SPACE. There was a lot of it, and not only in the extensive and now available no-man’s-land of the former wall-territory, but also, thanks to a generous sense of urban planning, in East Berlin’s many generous public spaces. There were also plenty of old and run-down buildings left in place because there had never been enough money for renovation or destructive modernisation.

This gave the Eastern part of the city a special flair, and made it, after much careful restoration, the more charismatic part of the capital. Many buildings – especially institutional and government structures – had fallen vacant in the post-wall period as a result of West Germany’s radical “liquidation campaign”[xiv], a process through which West German officials progressively closed down East-German institutions, factories and facilities.

Art organisers in West Berlin, who had previously been very spatially restricted, immediately recognised that this exceptional historical situation presented unique opportunities for Music, Visual Art and SoundArt - and they seized the moment. Between 1992-94, Matthias Osterwold, from Freunde Guter Musik was director of the music department at the Podewil (International Centre) – formerly the House of Young Talents, from were he transplanted the Freunde’s own brand of experimental music and performance into the heart of East Berlin.

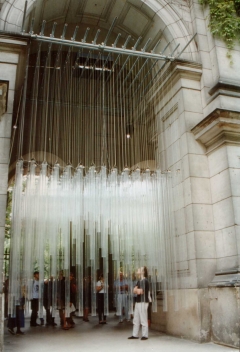

Podewil soon became an important centre for hybrid practices in music, performance and experiments with sound. The Freunde also managed to gain access to the Parochial Church – an old Baroque building right next to the Podewil, which had for years been used to store furniture. After negotiations with church officials, and the removal of the furniture, they began to organise concerts and SoundArt installations in the church’s spacious nave[xv].

This unique ripple in time-space at the beginning of the 1990’s was also exploited by the three curators, who in 1996 organised the festival that put Berlin at the centre of the world’s SoundArt map. Christian Kreisel from the Academy of Arts, freelance curator Georg Weckwerth and Matthias Osterwold from Freunde Guter Musik, curated the Sonambiente – Festival for listening and looking[xvi] – to celebrate the 300th anniversary of the Academy of Arts Berlin.

With over 100 invited artists it became the largest overview show of international SoundArt to be mounted anywhere[xvii]. In the space of a single month[xviii] at more than 20 reclaimed sites in the middle of East Berlin more than 80 projects were presented – occupying the grey zones between sound, music, noise and various visual media such as installation, object, projection, sculpture, painting, video, film, architecture, theatre and dance.

Lutz Glandien & Malte Lüders: Holle, 1996. Entrance to Berlin State Library, Unter den LindenApart from its survey character, the Festival followed the concept of Playing a City, which was previously conceived for, and road-tested at, the SoundArt ’95 Festival in Hannover.[xix] By visiting the various SoundArt sites, the public would at the same time be touring the city and since many of the works were located in open city spaces, they could also enjoy Berlin’s beautiful urban environments.

Lutz Glandien & Malte Lüders: Holle, 1996. Entrance to Berlin State Library, Unter den LindenApart from its survey character, the Festival followed the concept of Playing a City, which was previously conceived for, and road-tested at, the SoundArt ’95 Festival in Hannover.[xix] By visiting the various SoundArt sites, the public would at the same time be touring the city and since many of the works were located in open city spaces, they could also enjoy Berlin’s beautiful urban environments.

The installational part of the festival was accompanied by a framework programme of other events: concerts, a film series presenting remarkable collaborations between sound and moving image, happenings, dance- and theatre performances, and theoretical discussions. This festival also importantly produced a comprehensive catalogue that described not only the artists and their work, but also gave a valuable insight into the history, issues and debates of SoundArt, providing an impressive account of the self-awareness of the art form at that time.

The Sonambiente Festival captured the real enthusiasm for SoundArt in Berlin. A spirit of optimism and excitement had developed around the form, which was expressed through the many SA activities that emerged around and in the wake of the festival.

In 1995 Free Berlin Radio opened the SFB-Klanggalerie in the station’s beautiful atrium. It was the brainchild of RadioArt producer Manfred Mixner. This move from virtual radio space into real space was in keeping with the interest of many RadioArt producers in Germany’s Public Radio in the 1980’s and 90’s, who wished to pursue their sound experiments outside the radio.[xx]

A year after the opening of the SFB’s Klanggalerie, another sound gallery was opened - in the now re-designated Parochial Church: the Singuhr - Listening Gallery.[xxi] Under the artistic direction of Carsten Seiffart and Susanne Binas,[xxii] the Singuhr showed a wide array of SoundArt works, using all the spaces of the old Baroque building: the bell tower, the staircase and the foyer, the substantial nave and the outside areas. The Singuhr in Parochial quickly became an important international SoundArt centre.

In the 1990’s a significant number of small art galleries sprang up in East Berlin, a trend already visible before the fall of the wall, and several moved in experiment directions, and featured SoundArt works – Krammig & Pepper Contemporary, Galerie Klaus Fischer & Runge, Galerie Emerson, Galerie Eigen+Art.

When Berlin once again became the capital of Germany, investment in culture rocketed and several new museums were built – amongst them a new museum of contemporary arts, the Hamburger Bahnhof (1996). One year after its opening, in 1997, Freunde Guter Musik forged a collaboration with it, establishing the series Music Works By Visual Artists (Musikwerke Bildender Künstler). Spearheaded by Ingrid Buschmann, Gabriele Knapstein and Matthias Osterwold, this initiative first organised fringe concert events for exhibitions (such as the Sensation Exhibition on its tour from London) and soon began to realise independent, large-scale SoundArt works in the museum’s spacious facilities – such as Carsten Nicolai: Syn chron (2005 Neue Nationalgalerie), or Susan Philipsz: part file score (2014).[xxiii] Hamburger Bahnhof - main hall with Susan Philipz: part file score, 2014

Hamburger Bahnhof - main hall with Susan Philipz: part file score, 2014

In the second part of the 1990’s, with the increasing hybridisation of the Berlin art and music landscape, SoundArt became an integral part of the many newly established multi-media festivals – notably the Kryptonale (1994 - 2004), the Transmediale (since 1997) and the indestructible Inventionen. The Kryptonale, set up in 1994, was an interdisciplinary festival that focused on space-specific arts operating at the intersections between music, SoundArt, the visual arts, the performing arts and dance. An annual festival, it was run in the Wasserspeicher in Prenzlauer Berg – an empty Gründerzeit structure with two vast reservoir spaces. For ten years the Kryptonale built its programme around this eccentric building, inviting artists from a rainbow of backgrounds to explore its many facets.

Another Festival that had a permanent SoundArt presence was the Transmediale. Originally founded as VideoFilmFest (in 1988), it soon widened its profile to include new media. In 1997 it adopted its current name and became an annual international meeting point where artists and theoreticians could exchange works and ideas in the ever-expanding field of media art. Transmediale operates from the House of the Cultures of the World, and today affiliates with many outside initiatives and venues on collaborative projects, or hosts outside events.

Alongside cross-disciplinary or multimedia platforms, straight music festivals were also now routinely integrating SoundArt into their programmes. The Inventionen festival, for instance, fielded a substantial SoundArt presence in 2000 and 2002, with works like Robin Minard’s SoundBites 01, installed in the empty swimming pool of the Oderberger Straße (2002).[xxiv] Even a more hard-core music festival like Ultraschall might occasionally flirt with SoundArt.

By the end of the 20th century, Berlin had become the biggest building site in Central Europe. The former no-man’s-land and the area around the Potsdamer Platz were apportioned out between a number of giant companies, and an Art in Architecture (Kunst am Bau) scheme was introduced to draw attention to some of the building projects. Under this scheme, Christoph Metzger approached the HypoVereinsbank to sponsor a liaison between SoundArt and architecture, in which the bank agreed to make the sites of their Park Kolonnaden available for intermediate use at various stages of its construction. From 1999 to 2001, the Berlin Sound Art Forum realised eight sound installation projects by prominent SoundArt artists – starting with a large work by Christina Kubisch presented in the underground car park[xxv].

By the beginning of the new century, then, SoundArt had become completely integrated into the Berlin art scene and had even proved its commercial appeal. Change in the city was now in full swing and the gentrification of the old East was making rapid progress. Derelict buildings were being renovated and re-occupied, and unused institutional structures, like the Reichstag and the Staatsratsgebäude, were being refurbished and reclaimed by the new government. So by the time that the 2nd edition of the Sonambiente festival was launched in 2006, Berlin had changed radically, and not only in its spatial and cultural configurations. The economic crisis had finally become palpable and austerity measures were impacting negatively on public spending. Ten years after the first Sonambiente, the second had a very different feel. In only five central spaces, and a range of fringe locations, a matured SoundArt was presented. 50 artists, many of them now well known and established, showed new works; some brought works by their students; a new generation. And now that many of the main festival sites were corporate or newly constructed buildings [xxvi], the festival – despite the summer heat and the Football world cup fever – had a rather cold and slightly sterile feeling.

That year the Singuhr Gallery too had to move from the Parochial church to the Wasserspeicher in Prenzlauer Berg[xxvii]. This presented a considerable challenge for the curators’ aesthetic concept, both because of the highly reverberant nature of the two reservoir spaces and because of the limitations of its purpose-built architectural form. This inevitably constrained not only the kinds of sound works that could be presented, but also the artists who could be invited. The wide variety of SoundArt featured in the Parochial church gave way to a rather minimalist sound conception, which the gallery pursued until its final closure in May this year.

Even in these times of contraction, some new players entered the field. In 2009 Mario Mazzoli, a young Italian entrepreneur, opened a gallery “focusing on works in which sound is a crucial structural element”[xxviii], and made enormous efforts to make SoundArt commercially viable.

Douglas Henderson, Christina Kubisch, Robin Minard and many others showed their works here.

And occasionally unique opportunities just present themselves. So in 2009 – during the time between the final demolition of the Palace of the Republic and its replacement by the Berlin Castle - a very large, empty, public space was cleared in the heart of the city. Georg Weckwerth, who since 2003 has curated the TONSPUR for a public space in Vienna, seized this chance to install an unusual sound installation in a 150-meter long bench that cut across Castle Square. Along half its length he inserted loudspeakers and in the time frame of three years presented 14 sound projects in the TONSPUR in Berlin[xxix]. This window of opportunity closed when the building work at the Berlin Castle commenced.

Today

Today we find an established SoundArt field thoroughly integrated into the Berlin art and music landscape, in which SA works are routinely included as a permanent feature of festivals and events, like the contemporary music festival Maerzmusik[xxx] held every year at the Berliner Festspiele. Large and small art venues present SoundArt as a normal component of their exhibition programmes – as, for instance, at the Martin Gropius Bau in its 2007 exhibition From Spark to Pixel. Art + New Media. And, in 2013, the 14th International Poetry Festival Berlin commissioned the SoundArt exhibition Poetry as Art Sound as a part of their annual weeklong event at the Academy of Art, showing sound-space installations using spoken language by Gary Hill, Doug Henderson, Sabine Schäfer and Dieter Krebs.

SoundArt is now taught at Berlin universities like the University of Arts in Berlin or the Institut for New Music – Sound Time Space (Klangzeitort)[xxxi], and students venture with their works into Berlin’s public spaces. Gallery Rumpsti Pumsti, 2014

Gallery Rumpsti Pumsti, 2014

As sound technology gets easier to use, more and more artists from other fields are beginning to include sound in their work, and established SoundArt artists are now working with extreme finesse and subtlety – and on large scales. The next generation of new technology has opened up a whole new field of possibilities for SoundArt, encouraging mobile projects on a smaller and more local or communal scale - such as George Klein’s topsonie :: spree – a sound walk with a smartphone app.[xxxii]

In the 21st century, new art practices have evolved in which art is seen as a collaborative process between artists from different disciplines, as well as between artists and their public. These varying approaches were also applied to SoundArt. At the Errant Bodies project space (since 2010), American artist and author Brandon LaBelle, with a group of like-minded practitioners and theoreticians, pursues activities in which sound is not only used as artistic material, but explored both in its location (site-base art) and in the context of the lives of specific communities. Here SoundArt becomes practical research, an experimentation with spatial practices, fieldworks, performances and interventions.

Soundscape artists like Peter Cusack have been working this way for some time, so when he came to Berlin on a DAAD residence, he naturally joined forces with local environment groups. Tuned City, a project concerned with the relation between architecture and sound – kicked off with 5-day festival in Berlin in 2008, and since then has realised other events in Nürnberg, Tallin & Brüssels. The specific urban character and situations of each city supply the backdrop for each event.[xxxiii]

We can find other grass root activities at the Geräuscheladen Ohrenhoch where Katharina Moos and Knut Remond have been running a sound school for children aged 5 to 14, since 2008, introducing them to electroacoustic music, field recording, radio drama and sound installation. Every Sunday they run a listening event at which they invite well-known sound artists to present their work. And last but not least there is a small two-room basement space in Treptower Park that houses the Galerie Rumpsti Pumsti. SoundArt works are exhibited in one space and a treasure chest of related publications – CDs, LPs, books and pamphlets – are collected for sale in the other. These are also available through its mailorder service. The dedicated operator of this small independent venture is Daniel Löwenbrück who, by no accident I am sure, maintains good contact with SoundArt pioneer Rolf Langebartels, – bringing us back to the small flat in Berlin-Charlottenburg[xxxiv] from which the whole of Berlin’s SoundArt originally sprang. Gallery Rumpsti Pumsti, 2014.

Gallery Rumpsti Pumsti, 2014.

[i] German Academic Exchange Service, founded in 1925, “supporting the international exchange of students and scholars”. DAAD Homepage, About us, accessed May 14, https://www.daad.de/portrait/wer-wir-sind/kurzportrait/08940.en.html

[ii] F. Hein, ‘Klangkunst in elektronischen Studio’, accessed May 2014, http://www2.ak.tu-berlin.de/Geschichte/themen/TU-Klangkunst.html

[iii] Rolf Julius: Körperhorizont (Porträt von N.), 1980.

[iv] In 1987 Giannozzo became an art association (Kunstverein Giannozzo, Verein zur Förderung der aktuellen plastischen Kunst e.V.). It expanded its activities into different places and a variety of cross-genre events until it closed in 2008.

[v] R. Block, L. Dombois, N. Hertling (eds), Für Augen und Ohren – Von der Spieluhr zum akustischen Environment. Objekte - Installationen - Performances (Akademie-Katalog 127), Berlin, Akademie der Künste, 1980.

[vi] Spring 2014.

[vii] Hein, loc.cit.

[viii] See: Freunde Guter Musik, Programme May 1988, accessed May 2014, http://www.freunde-guter-musik-berlin.de/?cat=32&lang=en

[ix] Hein, loc.cit.

[x] ibid.

[xi] Jazz and Improv musicians maintained good contacts to the West, partly because of the intimate and flexible nature of their performance conditions.

[xii] Gruppe Neue Music Hanns Eisler Leipzig under the direction of Friedrich Schenker [see his Kammerspiel II Missa Nigra, 1979]

[xiii] Fine Kwiatkowski, Homepage, Vita – Zur Person, accessed May 2014, http://www.fine-k.de/vita/zur-person.html.

[xiv] The campaign was run under the term: “Abwicklung”.

[xv] See: Freunde Guter Musik Berlin e.V. Archive, Thematic Projects, accessed May 2014 http://www.freunde-guter-musik-berlin.de/?cat=32&lang=en

[xvi] Sonambiente - Festival für Hören und Sehen, Berlin 1996.

[xvii] H. de la Motte-Haber, M. Osterwold, G. Weckwerth (eds), Sonambiente Berlin 2006 (Catalogue), Heidelberg, Kehrer Verlag, 2006.

[xviii] 9 August - 8 September 1996.

[xix] Soundart 95. Internationales Klangkunstfestival, Hannover 1995, under the patronage of Rolf Liebermann, curated by Hans Gierschick Robert Jakobsen and Georg Weckwerth.

[xx] The SFB-Klanggalerie, Haus des Rundfunks, Berlin-Charlottenburg, 1995 – 2005.

[xxi] Singuhr – Hörgalerie in Parochial, Berlin-Mitte, 1996 – 2006.

[xxii] Today Prof. Susanne Binas-Peisendörfer.

[xxiii] Also: Janet Cardiff/ George Bures Miller: the murder of crows (2009), Ryoji Ikeda: db (2012).

[xxiv] Stadtbad Oderberger Straße, Berlin-Prenzlauer Berg 2002.

[xxv] Ch. Kubisch: Klang Fluß Licht Quelle, Klangkunstforum, Park Kolonnaden, Potsdamer Platz, Berlin-Tiergarten, 1999.

[xxvi] New Academy of Art building at the Pariser Platz, Alliance buildings at Ostbahnhof and Bahnhof Zoo, Foyer Dresdner Bank at the Pariser Platz and Bahnhof Postdamer Platz.

[xxvii] Singuhr im Wasserspeicher, Berlin-Prenzlauer Berg, 2006 – 2014.

[xxviii] Galerie Mario Mazzoli, Homepage, About us, accessed May 2014, http://www.galeriemazzoli.com/english/homeen.htm

[xxix] Schloßplatz, Berlin-Mitte, September 2009 - Januar 2013.

[xxx] MaerzMusic - Festival für aktuelle Musik - was launched in 2002 as part of the Berliner Festspiele, and until 2014 was curated by Matthias Osterwold.

[xxxi] Sound Studies at the Universität der Künste Berlin; KLANGZEITORT, Institut für Neue Musik der Universität der Künste Berlin und der Hochschule für Musik Hanns Eisler Berlin.

[xxxii] G. Klein: toposonie :: spree, Sound Walk in Berlin-Mitte, 2013, accessed May 2014. http://www.georgklein.de/installations/032_toposonie_e.html

[xxxiii] “The project draws on the traditions of critical discussion about urban space within the architecture and urban planning discourse–as well as its strategies and working methods–into the context of sound art.” Tuned City Home Page, accessed May 2014, http://www.tunedcity.net/?page_id=457

[xxxiv] Langebartels himself – 36 years later – still collects items relating to Sound and AudioArt in his online project Soundbag. Accessed May 2014, www.floraberlin.de/soundbag/