»For me, music is a journey through time; one song can send you back to a childhood summer, a packed dance floor, a breakup – or a sense of hope you thought you had given up.«

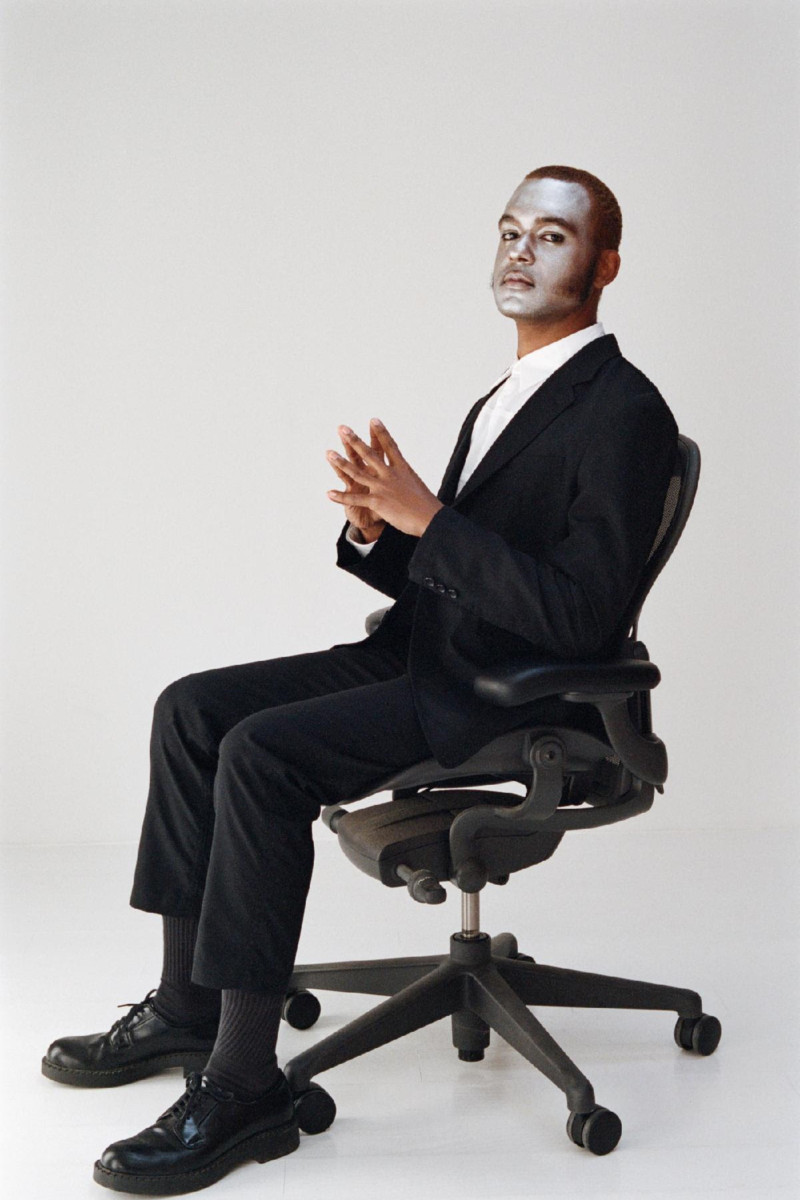

Danish-Corsican Malu Pierini has created her own musical universe somewhere between Copenhagen, Corsica and 1960s Paris. Here, Nordic soul/pop and French chanson meet as she draws threads to her family’s roots in the Parisian cabaret scene, the raw beauty of the Mediterranean and stories that bridge the gap between past and present. Pierini has just released her debut album Libera Me – a cinematic and personal journey into family history and an examination of what we carry with us from those who came before us. The album unites French 60s sounds, bossa references, Corsican folk tunes and indie pop in a story of love, heritage and identity.