A Case for Simplicity

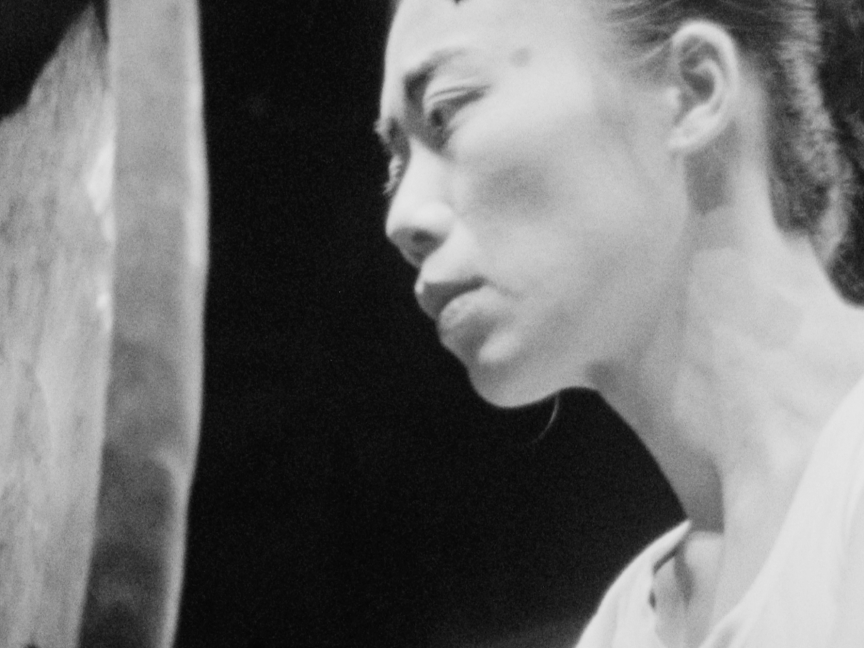

Never before have I found myself so far out on Refshaleøen – at least not without being at Copenhell. I’m almost at the island’s northernmost point when I, somewhat hesitantly, walk around a few unassuming buildings to find the rehearsal space where the Taiwanese-Danish percussionist and composer Ying-Hsueh Chen has agreed to meet me. Luckily it’s not raining, even though the sky is very grey, and luckily it’s not truly cold yet, even though the November air carries a faint chill.

»I have great trust in simplicity, and I think it’s a rare quality in our time«

At the exact moment my phone suddenly decides to emit an alarm sound, someone calls out to me from a nearby house. Wearing large glasses, a big hat, and an air of expectation, Chen comes towards me. We’ve met once before, eight or nine years ago, but we never get around to talking about that – there’s simply too much else to discuss.

I begin by looking through Chen’s extensive collection of instruments. There’s the more standard selection – bass drums, marimbas and the like – which she especially uses when performing works by Steve Reich and, not least, Iannis Xenakis, a composer whose music she has specialised in. And then there’s everything else: A woodblock from Taiwan – astonishingly heavy – which she entrusts me with. A pile of small, beautifully resonant fossilised sea urchins given to her by a musical friend. An empty bomb shell casing she once bought at a flea market on Refshaleøen, whose metallic tone she is very fond of. There are other flea-market finds too, and a series of small, homemade pieces of fired clay that produce incomparable sounds in her hand. The same is true of a few skeletal parts, which turn out to come from a red deer.

I’ve never heard Ying-Hsueh Chen live, but I’ve listened extensively to her two most recent albums (out of three), Dark Radiance (2023) and Mirage – An Architectural Sonic Experience (2025). Both are solo albums in which she often performs what she calls »meditations on a single instrument.« Both albums consist primarily of improvisations based on this concept – most tracks use only one instrument. Unlike her more virtuosity-driven debut Raw Elegance (2019), she insists on presenting the music on these two albums as simple and clear as possible.

Once we’ve settled at a small table by the window, Chen says: »I like it when art contains contradictions – when things are simple and at the same time deep, and not necessarily pleasing. Even small children could probably play something similar to what I do, like just striking a few stones, as on the opening track of Mirage. Some listeners might find what’s happening too simple, but it actually takes courage to dare to be simple – and it’s harder than people think to make that succeed for an audience.«

»It was as if the instrument itself cried out to me to be used in all sorts of ways.«

Sustainable rhythms

»I love complex music, especially the kind that points toward simplicity, while I struggle more with music that seems complex just for complexity’s sake.« She pauses, then adds: »I feel that many composers fear simplicity. I’m inspired by musicians and composers who are both virtuosic and able to play the simplest things beautifully – for me, that’s a hallmark of a great musician. I have great trust in simplicity, and I think it’s a rare quality in our time. That’s why I cultivate it myself.«

Exploring instruments is of particular importance to Chen: »I remember once being in a shop in Taiwan selling Buddhist and Taoist items used for religious rituals. I found a woodblock and began examining it, but the clerk came over and said: You’re a percussionist, so you should know you’re supposed to hit it only in the middle. But that was exactly what I didn’t want to do! I was interested in all the other sounds the instrument could produce, which also create structure – like the tabla in the Indian tradition. Compositionally, that means nurturing human complexity in thousands of contradictions, overtones, and patterns.«

»I love Steve Reich because his music is like looking through a microscope, where everything is magnified«

Chen elaborates: »It was as if the instrument itself cried out to me to be used in all sorts of ways. I think the woodblock liked being explored instead of just being a fixed ingredient in a temple, where it’s only ever struck in the middle.«

»I’m not very religious myself, so I actually think it’s a good thing when we start exploring the musical potential of religious instruments too. After all, shouldn’t it be the instrument – not taboos surrounding it – that determines how it should sound?«

»In general, I prefer to make music that starts from the instrument itself and explores it. I love Steve Reich because his music is like looking through a microscope, where everything is magnified. The same with Xenakis, whose music describes the mathematics behind nature. But I wish that composers working with percussion would spend more time understanding what a single drum can do instead of filling the score with complex rhythms.«

She continues: »This also ties into sustainability. Being a percussionist is such an expensive profession. It can take a very long time to learn complex works, and it’s resource-intensive when many instruments are needed at once. It creates an imbalance, especially because many works are performed only a few times – sometimes just once.«

»Only later did I discover that playing roof tiles and other ceramic instruments is actually common practice in Jatiwangi«

The sound of pre-modern time

Through her concert series Ancestral Modernism, Ying-Hsueh Chen has since 2014 performed over 100 concerts with different themes and collaborators. »This year,« she says, »I created a concert with the theme of earth, using only sound-makers and instruments made of stone and clay – nature’s own materials. I was deeply surprised by the richness of possibilities in, for example, playing a roof tile!

It was a family concert, and the children loved it! Only later did I discover that playing roof tiles and other ceramic instruments is actually common practice in Jatiwangi on the Indonesian island of Java. So I’m certainly not the first to experience that joy.«

»There are several dimensions to it,« Chen continues. »I’m interested in the immediacy that arises during improvisations with these more modest instruments. And I’m interested in how ‘music’ may have sounded in pre-modern times, for example in the Stone Age. I think there’s a reason that the simplest pulse has such universal appeal. Those red deer bones I showed you are actually from a Danish animal. They resemble some from the Ertebølle Stone Age culture, which fascinates me deeply.«

»With a natural instrument like a bone, you can play for maybe five minutes before the audience starts to get bored«

Chen reflects further: »In Scandinavia, Stone Age bones have been found with marks indicating they were used to make sound. So in a way, I’m joining that tradition. I imagine what they might have played – and I think their rhythms imitated the heartbeat.

The first time I picked up the red deer bones, I immediately knew how to play them. I struck the scapula with a rib as a drumstick, while using a hollow ossobuco bone in my left hand to strike the scapula. It was almost as if I had done it before in a previous life! I also quickly discovered that I could take another bone shaped like a ring and use it to beat the rhythm. My goal is to make music so universal that even my grandmother, who is illiterate, wouldn’t feel excluded. She would have liked the earth-concert and another concert I made entirely with unprocessed wood from nature.«

»When you improvise, you can only do what your body already knows«

»But there are things I really love about Western music, which improvised music doesn’t necessarily have – namely form and structure, the more architectural dimension of music. There’s something about proportions and golden ratios that inspires me when I play Bach. With a natural instrument like a bone, you can play for maybe five minutes before the audience starts to get bored. You need structure to avoid monotony.

It would require a score if I were to play for ten minutes or longer. When you improvise, you can only do what your body already knows – but with a score, you can go into more unfamiliar territory, which comes to you through preparation. It’s something I’m considering.«

The room as co-composer

The works on both Dark Radiance and Mirage are completely acoustic live recordings. Yet they sometimes sound as if they’re informed by industrial, electronica, and – on the marimba work »Dawn« – even ambient music. In that sense, the two albums speak into a much broader context, perhaps even unintentionally. On Mirage, she steps into the role of a site-oriented sound creator, where the surrounding space sometimes becomes part of the process – indeed, a kind of co-composer, as she puts it.

»I myself have given bad concerts because I was so focused on what I was supposed to play that I forgot to listen to the room I was in«

»Over the years, I’ve attended so many concerts where the music didn’t speak to or interact with the building at all. Not the slightest bit. It’s not entirely the musicians’ fault, because the concert hall as an institution is a static setting: No matter what kind of music is played, the frame is always the same.

I myself have given bad concerts because I was so focused on what I was supposed to play that I forgot to listen to the room I was in. I realised that I had to change that. So I began using the surrounding architectural space much more consciously.«

Several of the works have therefore been recorded in carefully chosen spaces, where the improvisations and instrumentation were shaped by the architecture, the acoustics, the distribution of sound. Grundtvig’s Church, the Brønshøj Water Tower, and Thorvaldsen’s Museum are among these sites. A clattering sound even gave the final work, »The Windows of Brønshøj Water Tower,« its title – a window at the top began reacting to the wind on a very blustery day, and the piece cannot be imagined without it, Chen says.

Only as I’m heading out the door do I think to ask how she actually ended up in Denmark

From New York to Refshaleøen

Only as I’m heading out the door do I think to ask how she actually ended up in Denmark. She explains that she originally studied in New York but felt uncomfortable with the city’s competitive environment – and with her teacher.

Then one day she came across an album by the Danish percussionist Gert Mortensen performing Per Nørgård’s I Ching, a work written specifically for him. From that moment, she knew he was the percussionist she wanted to study with. Chen moved to Denmark and continued her studies at the Royal Danish Academy of Music with Mortensen as her teacher. That she has since added Danish citizenship to her Taiwanese one suggests we’ll be fortunate enough to keep her here.

And I suspect there is still more wood, more bones, and many stones and roof tiles waiting to be played – even at the far end of Refshaleøen.

English translation: Andreo Michaelo Mielczarek