All the in-between spaces

The differences between the two cities could hardly be greater: the first is an eros-filled bustling megalopolis, cradle of civilisation, currently immersed in one of the most severe financial and social crises the continent has known. Kassel, on the other hand, is a typical West-German city, leveled by allied bombs during WWII and subsequently rebuilt and distinguished––aside from hosting documenta every five years for the past half century––for being the birthplace of the pedestrian zone (fondly referred to by the locals, as the Treppenstrasse).

Learning from Athens

The 14th edition of documenta, curated by 46-year-old Polish curator Adam Szymczyk, showcases works of 160 artists under the title “Learning from Athens”. In times of economic instability, an immigration crisis, and an austerity regime imposed by the German-led European Union, the project raised concerns of cultural imperialism and pity tourism. German critics and institution leaders expressed unease, questioning the curatorial potential of an exhibition taking place in two contrasting places as well as the possibility this change might reduce the number of visitors in Kassel, thus reducing the expected revenue from exhibition visitors. Working with a budget of 37 million euros, funded equally by governmental support and by visitors and private funding, this has been the most expensive documenta so far. “Dear Documenta, I refuse to exoticize myself to increase your cultural capital” reads one of the many graffitis covering the walls around exhibition venues in Athens.

Szymczyk’s stated curatorial intention was clearly to decolonise and question the predominant cultural supremacy of the west. As he writes in the exhibition’s reader: “[…] We see documenta 14, therefore, as exactly the acts that can be carried out by anyone and everyone as a diverse, ever-changing, transitional, and anti-identitarian parliament of bodies – of all bodies coming together in documenta 14 […] It seemed pertinent to learn how to work and act from Athens, where we might begin to learn how to see the world again in an unprejudiced way, unlearning and abandoning the predominant cultural conditioning that, silently or explicitly, presupposes the supremacy of the West, its institutions and culture, over the “barbarian” and supposedly untrustworthy, unable, unenlightened, ever to be subjugated “rest”[…] the move of documenta to Athens, in order to unlearn what we know, and not to give its people lessons, is meant to open up a space of possibility”. He thus set an extremely high political bar for the event itself.

A hundred day event

Since its inception, documenta has sought to represent the current state of the art world. 1970s documenta Nr. 5, curated by Harald Szeemann, was a seminal exhibition, representing the shift from object-based art works towards an activistic, performance oriented program. The hundred day museum turned into a hundred day event. This year’s exhibition takes this idea even further, presenting a program saturated with concerts, performance and sound art to a more substantial than ever before. Inspired by the twentieth century Greek composer Jani Christou’s “Continuum”, documenta 14 enacts a score of multiple events and actions, taking place over an undefined period of time. The curatorial choice to engage with music and performance is part of its attempt to engage the audience with the art-work in participatory ways. Questions and issues concerning identity, migration, politics and value are the common thread connecting the works presented.Located in the heart of the city, is the Athens Conservatoire (in Greek, Odeion Athinon), turned into one of the main exhibition venues. The Bauhaus building, designed by the Greek architect Ioannis Despotopoulos, is the only completed part of a large scale urban plan for a cultural complex commissioned in 1959 by the Greek government of its day. Established in 1871, initially, violin and flute were the only instruments taught in the institute, following the ancient Greek Apollonian and Dionysian aesthetic principles. The Odeion was one of the central exhibition venues of documenta 14, featuring sound art, graphic and text scores, installations and video works. Athens Conservatoire (Odeion)

Athens Conservatoire (Odeion)

Back in Berlin after visiting the Athenian part of the exhibition, I was curious to know more about how the project evolved, and particularly, how music and sound art came to play such a central role within the exhibition. Paolo Thorsen-Nagel, Sound and Music Advisor at this year’s documenta, kindly agreed to Skype and discuss the exhibition.

“I don't think, at least from my perspective, that there was a prefabricated plan for music to take such a central role in the exhibition,” replies Paolo, after I asked him about the centrality of sound art and music to this year’s edition. He continues: “I believe one of Adam Szymczyk’s reasons to include sound quite extensively, especially so in Athens, is its social aspect. There is something quite immediate about the way music and sound transcend a somewhat intellectual grasp of what's going on — in that moment, but also in a wider sense, instantly transmitting an understanding of time and place and how these are conditioned. Especially in Athens, projects centered around music, it's presentation and perception, seemed a natural way of involving the community.”

Together with a team of curators, writers and editors, Paolo began working in Athens almost two years ago and immersed himself in the city, while establishing connections and collaborations with local musicians.

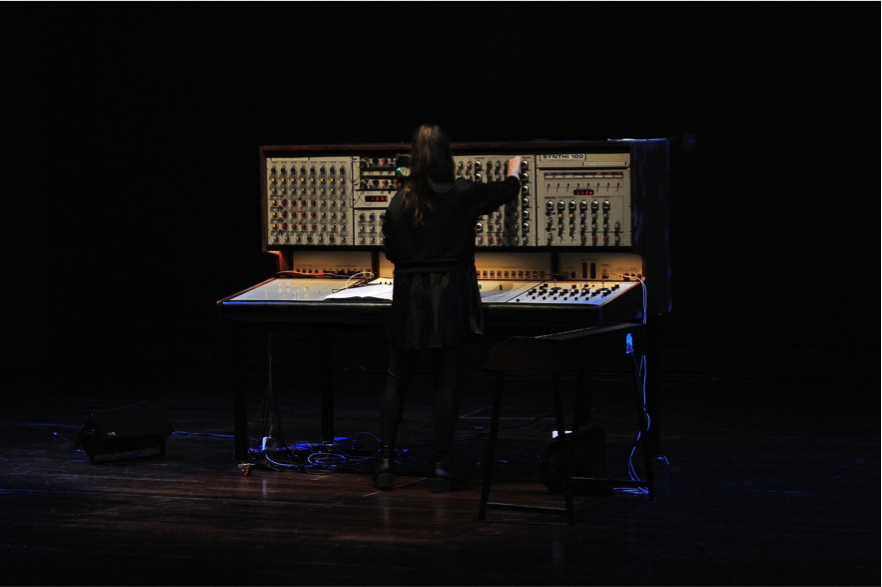

Synthi 100

“One of the projects that has an immediate connection to Athens is the collaboration with KSYME-CMRC, Athens’ Contemporary Music Research Center. The project is centred around the institute's EMS Synthi 100, a modular synthesizer which was featured in the documenta 14’ exhibition at the Odeion. KSYME-CMRC was founded in Athens in 1979 by Iannis Xenakis, Giannis G. Papaioannou, and Stephanos Vassiliadis, with the aim of developing electro-acoustic music and sound practices in Greece. It coincided with the fall of the dictatorship here and the fact that Xenakis had decided to come back to Athens after being in exile in France for over two decades. After working with institutions like GRM and IRCAM in France, he wanted to set up a base for electro-acoustic developments in Greece, together with other Greek composers.

At the time only twenty-five modular synths were produced according to this model, and there are only four of them currently known to be in working condition worldwide. Ksyme’s state funding ceased in the 1980s, and the Synthi had not been repaired since then. After a discussion with the institute about possible support and collaboration, it was decided that documenta 14 would fund the restoration of the Synthi 100.

“This was of course very interesting to us, because in this way we could help re-establish an interest in KSYME as a contemporary music institution well beyond the presence of documenta 14. The prospect of KSYME housing one of these rare synthesizers in working condition could attract interest from national and international like-minded institutions and composers, as well as serve as an object for artistic exchange, one of which we initiated later in the process, with the Stockholm institutions EMS (Elektronmusikstudion) and Fylkingen (venue for New Music and Intermedia Art)”.

After collaborating with EMS (Elektronmusikstudion), the center for electronic music and sound art in Stockholm, on the restoration of the instrument, four pieces were commissioned for the Synthi by documenta 14, which Panos Alexiadis, Jonas Broberg, Marinos Koutsomichalis, and Lisa Stenberg developed at KSYME and performed at Megaron, the Athens Concert Hall (which also served as a venue for documenta 14) during a two-day symposium on electronic music in Greece and Sweden. Paul Pignon, one of the first engineers to work with the Synthi after its inception, was invited by Paolo to create an automated patch which played inside the exhibition for the rest of its duration. KSYME-CMRC, archival materials, installation view, Athens Conservatoire (Odeion), Athens, documenta 14

KSYME-CMRC, archival materials, installation view, Athens Conservatoire (Odeion), Athens, documenta 14 Lisa Stenberg, concert, KSYME-CMRC, EMS and Fylkingen: Electronic Music from Greece and Sweden, Megaron, The Athens Concert Hall

Lisa Stenberg, concert, KSYME-CMRC, EMS and Fylkingen: Electronic Music from Greece and Sweden, Megaron, The Athens Concert Hall

Jani Christou’s “Continuum”

Jani Christou’s Epicycle was one of the pieces performed during the opening of the exhibition. The composer’s scores, sketches and writings such as Project 21, Mysterion and The Strychnine Lady were featured at the Odeion. I asked Paolo about the choice of the piece and its performance: “There is a part in the score that invokes a meta level, it is outside of the concert performance as we have come to know it and yet it's part of the piece. Christou describes it as a “Continuum,” a part in the score to which has no beginning or end, and anyone can step into and out of that zone and participate. Epicycle's Continuum served as the framework for our work here in Athens and documenta at large; some months before the opening of the exhibition in Athens we initiated the Continuum and with it a series of semi-public events that shared our thinking with students of the Fine Arts School of Athens and other local collaborators. The Austrian conductor Rupert Huber, one of Christou's close collaborators, studied the piece with us and we later performed a version of it together with the d14 artists and team during the press conference for the opening in Athens.” Jani Christou, Epicycle (1968), musical score (excerpt), Athens Conservatoire (Odeion), Athens, documenta 14.

Jani Christou, Epicycle (1968), musical score (excerpt), Athens Conservatoire (Odeion), Athens, documenta 14.

Scores and other objects

Entering Odeion’s ground floor, one encountered Nevin Aladağ’s furniture pieces, turned into musical instruments by the artist. The carefully crafted objects —mid-twentieth-century modernist design which reverberated with the building’s architecture—were occasionally activated by performers. Though during my visit (and, I can imagine, this was often the case), they remained frozen and silent, aesthetic objects. Graphic scores by Pauline Oliveros, Cornelius Cardew and Jakob Ullmann, were displayed in vitrines and hung on walls, revealing different compositional approaches, visual representation of sounds, as well as text-scores. “We were interested in the possibilities of the visual representation of the physical experience that music is, or, rather, not so much a visual representation but more the sound that is created by the visual, seemingly mute objects” says Paolo, “... and conversely, I think the scores were important catalysts for us to put together such an extensive performed sound and music programme, as an activation and extension of what people saw on display in the exhibition.”  Nevin Aladağ, Music Room (Athens), 2017, Athens Conservatoire (Odeion), Athens, documenta 14, © Nevin Aladağ/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Nevin Aladağ, Music Room (Athens), 2017, Athens Conservatoire (Odeion), Athens, documenta 14, © Nevin Aladağ/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn Pauline Oliveros, Score for Composition, ca. 1981, Athens Conservatoire (Odeion), documenta 14.

Pauline Oliveros, Score for Composition, ca. 1981, Athens Conservatoire (Odeion), documenta 14.

Pauline Oliveros’ text-scores for The documenta 14 Reader as well as her works presented at the exhibition were one of the last projects Oliveros worked on prior to her death. “What I felt was so important about her work to also feature in the exhibition, was this interest in music and sound as being something that is very much an expression of life, an expression of politics and the society it happens in. I think this was somewhat of a guiding principle for the entire music and sound programme — to situate music within the vast sonic vortex we move in daily and to understand it as an expression also of the non-aural world.”

Conversations with fellow visitors revealed a gap between the curatorial intention – “the move of documenta to Athens, in order to unlearn what we know, and not to give its people lessons, is meant to open up a space of possibility” – and the audience’s as well as the locals’ experience. The works on display often felt distant, ambiguous and hermetic; the text accompanying them in many cases made the experience even worse.

Amongst the abundance of original scores on display, visiting the exhibition with non-musician friends raised the question of the significance of exhibiting such artefacts, without providing audio samples of the work. After I noticed that the scores didn’t resonate with my non-musician friends, we experimented with performing Oliveros’ Tuning Meditation. Activating the mute score made quite a difference. Presented this way, in vitrines or behind framed glass, were the scores being fetishized? I queried.

“Well, yeah, I see what you're saying. For someone that doesn't have any idea about Cornelius Cardew or Pauline Oliveros, it might be hard to understand what their work is all about. At the same time we weren't interested in isolated or complete showcases of individual artists with sound accompanying the score – if scores of certain composers were included in the exhibition they were meant to present crucial facets of the artist's work, their philosophy and working methods, or simply be autonomous works. In this way they can hopefully be understood in their commonality and as examples that connect to larger ideas of composition, writing and social organisation present elsewhere in the exhibition. If audio examples of the scores weren't present in the exhibit — and I mostly think they wouldn't make for a very broad understanding of the work, a recording being just one version confined in the space of the audio interface and headphones — we focused on their live activation through concerts and performances in the Listening Space program and the concert series at Megaron Mousikis. In this way, the sound programme in Athens, and Listening Space in particular, was very much intended for the local audience who could attend the weekly performances, concerts, and talks, rather than just the international audience who might only be in Athens for two or three days.” Akio Suzuki and Aki Onda, performance, Listening Space, Athens Conservatoire (Odeion), Athens, documenta 14.

Akio Suzuki and Aki Onda, performance, Listening Space, Athens Conservatoire (Odeion), Athens, documenta 14.

Concerts in the in-between spaces

Alongside the exhibition a series of nine concerts was presented at Megaron, Athens' central Concert Hall. Pieces by Christou, Julius Eastman, Jakob Ullmann, Éliane Radigue, Graciela Paraskevaídis and others were performed. “The concert series was conceived as a whole. We were thinking of works that express crucial moments in history as well as composers whose work has strong sociopolitical connotations, for instance Frederic Rzewski’s People United Will Never Be Defeated!”

Another aspect of the more experimentally tinged Listening Space programme engaged with the architecture of the Megaron. "I put together a night called ‘All the in-between spaces’. There is an old part and new part of the Megaron,” Paolo elaborates, “four performances took place throughout the evening. Moving through the building complex, we started in the old part and wandered on to the new one as the night continued, playing in various foyers and staircases with the aim of activating these simultaneously decadent and vacant spaces, ascribing a sonic quality to them, parallel to those of the actual concert halls the building holds.”

In addition to the main concert series, Paolo curated a project titled ‘Listening Space’: “I had proposed this project upon being invited as Sound and Music advisor to documenta 14, with the ambition to present a live programme of music and sound that would allow for a sonic experience of various locations in Athens, collaborating with different existing institutions and bringing together various artists and musicians, both local and international. Besides expressing crucial sonic ideas of the exhibition in the format of a concert, the idea for the programme was for artists to engage in whichever space they were performing in, taking into account its architecture and infrastructure, the surroundings and social milieu but also imbuing a sense of listening through their performance, the execution and the setup of it. So the title of the program translates its meaning quite literally and hints at the inextricable dualism of sounding a physical space and the space created by listening itself”. Giorgos Axiotis & Efthimis Theodossis, performance, Listening Space, Pikionis Pavilion, Athens, documenta 14.

Giorgos Axiotis & Efthimis Theodossis, performance, Listening Space, Pikionis Pavilion, Athens, documenta 14.

The programme, which was realized in Athens, and for which Paolo created a kind of living archive in the form of a listening station in Kassel, combined various artists, performances ranging from electronic experimental music to lecture performances that dealt with the intersection of architectural space in sound and acoustics, the psychological effect on the listener, and the use of architectural modifications to designate specific areas within the contained space and their sonic qualities. The programme also included immersive concerts with multiple speakers and an “Electrical Walk” through the city with Christina Kubisch.

I asked Paolo whether he thinks the programme might be carried on in the future, and he replied: “I hope so. I can say that there has been great interest in the Listening Space programme and also in the concert programme at Megaron. It seems to be something that people know of, and look forward to and return to. I think it has been felt that all of these spaces we occupied and infiltrated for these events have really been used in very specific ways that resonate with the audience and the performers alike. I hope there is this kind of urge to continue something similar in the future. I do remember the Minister of Culture sitting on the steps in one of the Megaron foyers, just in front of Panos Charalambous during his performance for the ‘All the in-between spaces’ night; we talked afterwards and she just seemed to be very happy about this kind of different usage of this institution and seeing a mass of people occupying these slightly sterile spaces, breathing a different air and sound into their opulent design.” Panos Charalambous, Voice-O-Graph, performance. All the in-between spaces / Listening Space, Athens Contert Hall, documenta 14

Panos Charalambous, Voice-O-Graph, performance. All the in-between spaces / Listening Space, Athens Contert Hall, documenta 14

Visiting Athens for a couple of days, the metropolitan bustling soundscape was one of the first things that drew my attention. Coming from northern Europe, where apartments are well insulated, the streets seem distant. In Athens, with windows wide open to the pleasant mediterranean breeze, interiors and exteriors blend. I welcomed the wakeful sounds of the city into my room, slightly nostalgic for those of my own mediterranean upbringing. Reflecting upon this soundscape and the days I spent at the Odeion, the two seemed to come together, leaving the colder climate of northern Europe as a distant memory. In this overwhelming, dense, sprawling, and often frustrating exhibition, focusing on the music and sound art programme enabled one to participate in this experience in a more unified and inspiring way. Mette Henriette, In Between, performance, All the in-between spaces / Listening Space, The Athens Concert Hall, documents 14

Mette Henriette, In Between, performance, All the in-between spaces / Listening Space, The Athens Concert Hall, documents 14