»Music is hope, confusion, and memory talking with each other, leading us toward futures we haven't yet imagined.«

Patrick Becker is co-director of the Wolke Verlag publishing house and co-editor of the contemporary music magazine Positionen.

The red Husqvarna sewing machine stood centre stage, buzzing relentlessly like a tireless drummer locked in an endless blast beat. »Järnrör«, »Cyanid«, »Tramadol«, Tehran hissed between squealing guitar amplifiers and in front of videos showing idyllic Swedish roadside art and images of the many Husqvarna weapons. For behind Husqvarna’s innocent garden and household products lies an industry of death – a prism of growing up in Jönköping and an illusion of Swedish neutrality, which the Swedish-Iranian artist Tehran underscored with the concert Husqvarna The Movie.

Each track came with a new video bathed in sewing machine, guitar and growl vocals. But the song »Delam gerefteh« was more subdued, not least because Tehran leaned back in a chair, cigarette in mouth, letting the music and the video speak for themselves.

The evening’s second name, the Canadian-Iranian Saint Abdullah, spent the entire concert with a marker pen in his mouth, occasionally using it to jot down the course of the music. Saint Abdullah’s performance was like watching a radio operator adjusting a crackling signal – from birdsong to acoustic guitar, from news broadcasts to field recordings, the sampler at the centre of the table became a focal point for fragments of faith, culture and migration.

Where Tehran’s concert felt like a rehearsed, healing ritual, Saint Abdullah’s unfolded as an impulsive dialogue between a sea of sound bites. Both performances revolved around Iranian heritage. Not a heritage that necessarily needs to be understood, but one that appears as a mosaic of contradictions – and can only truly be processed in one place: in music.

»Music is hope, confusion, and memory talking with each other, leading us toward futures we haven't yet imagined.«

Patrick Becker is co-director of the Wolke Verlag publishing house and co-editor of the contemporary music magazine Positionen.

»A lot is projected onto music and making music – I'm careful, singing doesn't make you more intelligent and certainly doesn't make you a better person. It's like in sexuality. A lot of things go very consciously wrong for some people. Music like sex are means of communication, people come into contact and negotiate with each other and their instruments/tools and meet themselves in it. This is also the case when I listen to music – from every conceivable genre and context, even if I always notice that as a teenager I used to play a lot of jazz guitar.«

Bastian Zimmermann lives in Munich and works freelance in the areas of music and performance. As a dramaturge, he works with artists such as the soloist ensemble Kaleidoskop, Yael Ronen and Neo Hülcker. He is editor of the German speaking magazine Positionen – Texts on Current Music and curates projects such as »Music for Hotel Bars« and the festival Music Installations Nuremberg festival. His focus is on social aspects of making music, experimental music concepts and the questioning of bourgeois structures in contemporary music. In Spring 2025 he will take over the Wolke Verlag publishing house for books on music with Patrick Becker.

»Music to me is… my work. I've landed in the best job in the world, where a core task is to discover new music, to learn its internal logic and aesthetics, who created it, and why. I'm a music researcher and have just returned from the island of Java in Indonesia with my research partner and husband Nils, where we've been visiting experimental musicians in Yogyakarta – artists we've now followed for seven years.

One recurring theme is the trance/horse dance jathilan (or jaranan), which several of the artists have introduced us to. Jathilan is on one hand an old Javanese ritual, and on the other hand a contemporary (village) culture in full development. There is no single historically 'correct' jathilan. It's a practice that follows an old spiritual ritual, but is also open to current Indonesian influences.

The playlist consists of three tracks by Senyawa, Gabber Modus Operandi, and Raja Kirik, all of whom have incorporated the ritual into their music. The fourth track was supposed to be a 'traditional' jathilan, but as far as I know, no such recording exists on Spotify. Instead, I found a related jaranan piece that includes a dangdut song – an ultra-popular genre that is often performed as part of a jathilan event. The final track is one of the most popular dangdut songs at the moment.«

Sanne Krogh Groth is Associate Professor of Musicology at Lund University, Sweden, where she conducts research on electronic music and sound art, currently with a focus on Indonesia. Sanne was editor-in-chief of Seismograf from 2011–2019. In 2015, she established Seismograf Peer, which she is still the managing editor of.

»For me, music is work and a way to escape it. Music is the fanciest way of communication and therefore the most delicious food for analysis. It is what prolongs your feeling for longer than you can physically hold. Music is something after which you say: 'I’m glad you didn’t use words'. After all, it’s something that makes your commute or chores shorter, and this time-controlling function is the very first and foremost mystery I love about it.«

Liza Sirenko is a music theorist and music critic from Kharkiv, Ukraine. She is a co-founder and board member of the Ukrainian media about classical music The Claquers. She is a former Fulbright Visiting Scholar at the Graduate Center, CUNY (New York, USA), and a graduate of National Music Academy of Ukraine (Kyiv, Ukraine). Her current interests include processes in the classical music industry, contemporary opera in Ukraine, and a role of postcolonial moves in these. Liza is a former PR Director of the Kyiv Symphony Orchestra, currently working as a Program Officer at the Goethe-Institut Ukraine.

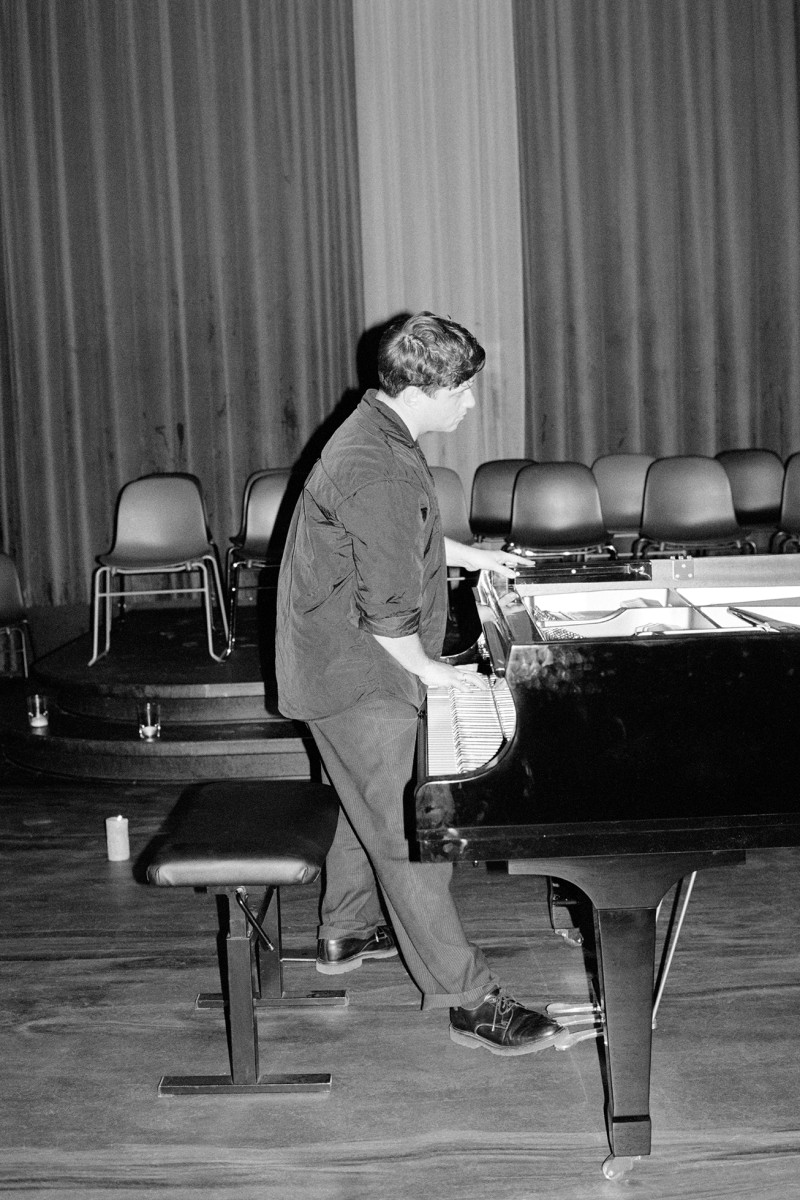

»Is he going to play three pianos?« a boy asks. »Maybe he’s learned to play with his feet?« says an adult man. The audience on their way into the DR Concert Hall’s main auditorium comment on the setup for August Rosenbaum’s piano concert. Three Steinway grand pianos lined up is truly peculiar – actually comical.

When the concert began, I imagined I could hear differences between the instruments, though I would probably fail a blind test. Apart from a bit of playing with staccato on one piano and pedal on another, the setup was, frankly, underused. The piano playing was lacking, dominated by a single approach: pedal pressed all the way down, an active right hand primarily in the middle register, a left hand with a muted accompaniment, and a great deal of repetitive technique.

It felt like a gravity Rosenbaum could not escape. No idea or direction could break free; one always returned to the same place.

When there are two grand pianos for a concert, one of them is usually prepared. Rosenbaum had three (!) without using a single screw, coin, or ping-pong ball. Shouldn’t that be a criminal offense? Nor were any extended techniques employed, such as clusters or playing with the back of the hand.

The light show was charming, at times impressive. Still, it takes more goodwill than I possess to call the evening an audiovisual concert, as the program text told me it was. On the way out, I heard another man say, »It was actually quite exciting to hear him play.« I didn’t think so.

English translation: Andreo Michaelo Mielczarek