Skjulte minder om solstråler

»There is the art of memory and there is the memory of art,« skriver den franske filosof Jacques Derrida. Og mindet som kunst, får jeg lyst til at tilføje efter at have lyttet til det nye album med konkretistiske lydkollager af argentinske Beatriz Ferreyra og britiske Natasha Barrett.

‘Souvenirs cachés’ betyder direkte oversat ‘skjulte minder’, og hele albummet lyder rent faktisk som en samling erindringer, der i korte glimt træder frem fra underbevidsthedens slør. Jeg hører fuglesang og summende insekter i det væld af hviskende stemmer og langstrakte droner, der udgør Ferreyras Souvenirs cachés, jeg mærker den varme, kildende fornemmelse af en solstråle, der langsomt bevæger sig ned ad min ryg. Et sepiatonet minde om den perfekte sommerdags flygtige sødme.

Barretts Innermost lyder knap så idyllisk. Et marchorkesters insisterende rytme, klapsalver og hujende tilråb fra en forsamling er gentagne motiver, der uhjælpeligt leder mine tanker mod romantiserede idéer om revolution. Gennem hele værket sidder jeg og venter på, at marchtrommerne kulminerer i et storslået crescendo, men det sker aldrig. I stedet er det – et minut inden værket slutter – som om nogen kaster et vattæppe over lyden, som om dens kanter slibes af med sandpapir. Som om Barretts ultradetaljerede lydunivers med et – for igen at låne en formulering fra Derrida – »sinks into an abyss from which no memory […] can save it«.

The Art of Decay

It's seriously clammy as you step down into the Cisterns beneath Søndermarken – humid, with brick columns dripping with condensation and chalk stalactites hanging down. A piano has been left down here for five months, slowly deteriorating. I was skeptical about Opløsninger: yet another Annea Lockwood-inspired work, simply inflicting violence on a poor instrument? And if not, is a composer like August Rosenbaum, who works with short, vibe-friendly piano pieces, the right person to elevate the idea into something greater? Yes, as it turns out, fortunately.

Together with visual artist Ea Verdoner, Rosenbaum has created an installation piece that spans three chambers, and in the first, you indeed see the decayed piano with centimeter-thick mold patches on the keys. As you shuffle along to the second chamber, Rosenbaum sits in the dark in front of a better-preserved grand piano. His playing is both minimalist and grandiose, but it’s the breaks in the composition that truly captivate me. Half motifs, repeated triplets, tritone-like intervals. Rosenbaum loops a captured sound from the decayed piano on a sequencer, gets up, and walks away briskly. He returns and turns up the industrial rumble of a gong, as if he were Trent Reznor in the studio. Combined with choreography about duality, a voice-over about life and birth, and a video about the body and decay, it becomes an exciting and reasonably new depiction of the raw, cold, and arbitrary nature of decomposition.

The Perfect Storm

It is rare for an album to be complimented for lulling someone to sleep. But after a month with the album Cymatic by the Swiss-resident, Hong Kong-born Natalja Romine, I have often found myself slipping into dreamland – something I rarely consider a good thing. In the case of Cymatic, however, it is a clear strength. Yanling comes from the world of art music, and the work has already been presented in that context. Still, it stands strong as a piece of cinematic sci-fi ambient. Names like Jean-Michel Jarre, Brian Eno, and Hans Zimmer haunt the album, as modular noise clouds, female vocals, and mysterious electronic pulses and sine waves blend together to create a harmonious tapestry. It is not groundbreaking, and the tracks can be difficult to distinguish from one another. Nevertheless, the captivating piano riffs on »Transmuted« and the gurgling bass synths on »Nebula« stand out. On »Fallen Tempest«, choirs, chords, and reverb coalesce into a higher unity, and on the album's pinnacle, »Aura Nova«, sudden synth stabs threaten to wake one from the dream.

Cymatic is not a masterpiece and can appear on gray days as disposable ambient for a Hollywood blockbuster no one wants to watch. But over time, it grows into a brilliant piece of contemporary art, only suffering from slightly too perfect production and somewhat grandiose gestures. Why get upset over the storm in your teacup if it storms in the right way?

English translation: Andreo Michaelo Mielczarek

If John Malkovich Could Sing, It Would be Devilish Singing

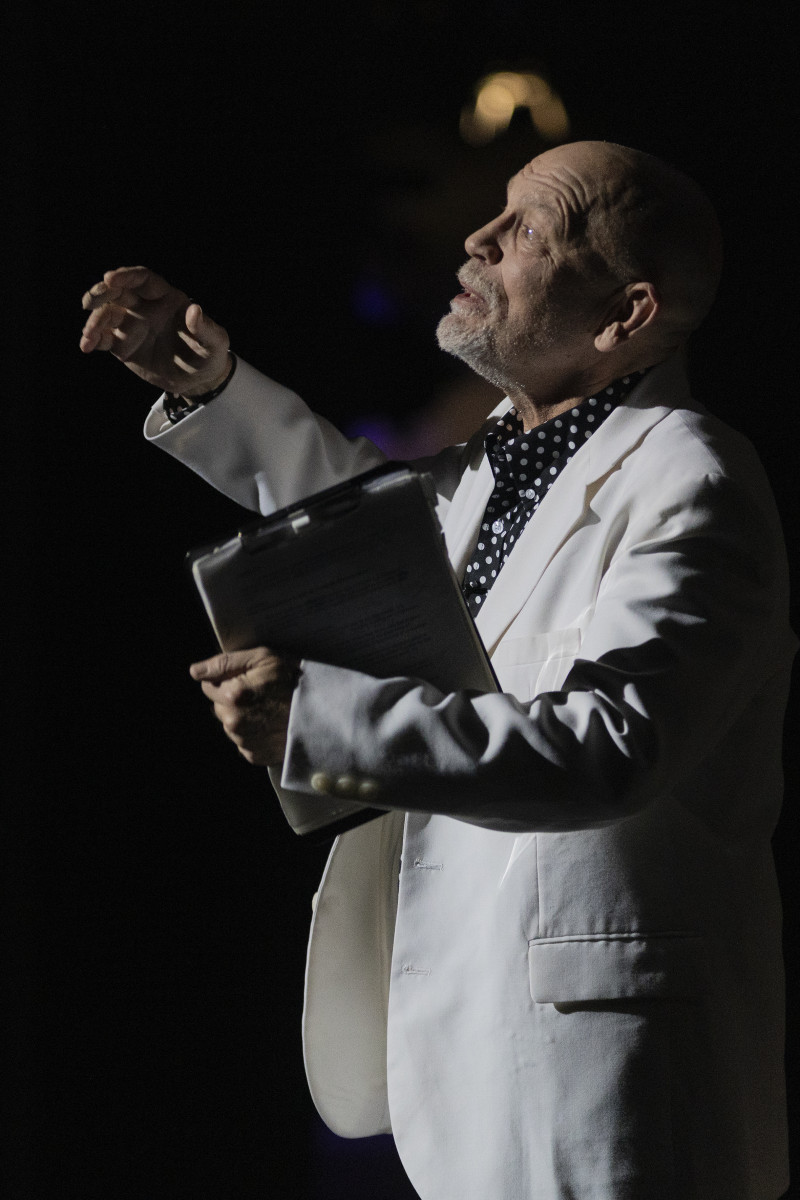

»Please, conductor play and give me some fucking peace«. The mass murderer – and now a writer, as he became one in prison – Jack Unterweger (John Malkovich) demands more »old fashioned music« as he talks about his barbaric actions in the forests of Vienna. We are at Unterweger's book reception. The baroque orchestra Orchester Wiener Akademie sits on stage as witnesses, while Malkovich strangles sopranos Marie Arnet and Theodora Raftis with their underwear to arias by Mozart, Vivaldi and Haydn. Yes, opera is often about men hitting on women.

»I don't usually like this kind of music, it makes me nervous«. Yes, of course, because the baroque music played on period instruments is not just lame background music, but an active narrator which »disrupts« the sales pitch of a monologue, and the repulsive truth that Malkovich wants to share with us – the murder of nine prostitutes. He would rather be a murderer than nothing, he says. But the two singers also make him roll on the ground like a child; he gasps, becomes uncomfortable in his white suit. These moments elevate The Infernal Comedy to more than a clever concept (well-known actor, ok well-known orchestra, authentic murder story). The women gain a glimmer of dignity, while Malkovich's Unterweger loses it. Now what is he without Dandy sunglasses?

The Infernal Comedy was created for Malkovich in 2008, his joker face, his swaying, yes über musical voice. We want to buy his books because evil sells. As a super simple chamber music piece it works. If Malkovich suddenly announced that he now wanted to sing opera, we would also buy a ticket. But how would this story of misogyny sound with the baroque music of 2024?

Drums of Dissent

With her latest album, saxofonist and composer Maria Faust has put the political at the center of jazz, in the long tradition of Ornette Coleman, Miles Davis, Charlie Haden, Fred Frith and Tom Cora, just to name a few. What is surprising is her choice of genre, marches, which is not a per se a traditional jazz form. If Charles Mingus, for instance, payed his tribute to New Orleans marching bands, Faust’s choice is definitely antagonistic. The marches she manipulates and destroys from the inside are not of the entertaining sort, unless you’re a general, as they are of the military and nationalistic kind.

Faust’s score would be a perfect fit for plays like Alphonse Allais’s Père Ubu and Bertold Brecht’s The Resistible Ascension of Arturo Ui, in its use of the grotesque as a creative driving force. Faust’s genius however doesn’t lie in turning these marches into farcical circus fanfares, but in creating a truly threatening space within the music, through chaos but also heart-breaking dissonances, which could be heard as a reminiscence of the wailers mourning their dead fallen in the war. Her fairly large ensemble – seven musicians, plus herself – which is composed of six horns and two drums/percussion creates a perfect harmony-disharmony universe, as if Charles Mingus and Sun Ra had worked together.

Marches Rewound and Rewritten is a seminal and important album which shines darkly in these difficult times and reminds us that everything is political – especially music.

A Seedy Hotel Room Becomes the Stage For Lives, Traumas, and Music

Two chamber operas by Irish composer Emma O’Halloran, both adapted from plays by her uncle, Mark O’Halloran. The first, Trade, is utterly compelling and deeply moving: the story of two men meeting for sex in a grubby hotel room, whose intertwining lives are burdened by trauma and love. The composer writes of the »beautiful economy« in her uncle’s language and the same could be said of her music, which charges the text with more and more tension and urgency without cramping it – but just as often barely registers at all, letting theatre and storytelling rule. The vocal acting is outstanding.

The stylistic resourcefulness of Trade, in which the two characters are so vividly drawn, returns in the monologue Mary Motorhead but with less success. Here, musical sampling can get in the way of our view of the prisoner, who tells of her troubled life before she split her husband’s head open with a knife. Taken with Trade, though, it only emphasizes O’Halloran’s brilliance with theatre and deft musical hand. Would it be too much to hope for one or two truly theatrical, storytelling operas like these in the avant-garde strand of Copenhagen Opera Festival?