»Music to me is – having spent a lot of time listening, composing, and thinking about it – still, essentially, a mystery.«

Bortset fra den første onsdag i maj er sirener i Danmark nærmest udelukkende noget, vi hører i forbindelse med udrykninger, men i adskillige andre lande er sirener en integreret del af den lydlige hverdag. Sirener er på mange måder et fascinerende fænomen, der på én gang signalerer både overlevelse og katastrofe, og de er et helt fast sonisk inventar i især krigszoner og steder, der på den eller anden måde er risikoområder.

Den spanskfødte multikunstner Aura Satz’ 90 minutters dokumentarfilm, Preemptive Listening – der på dansk kan oversættes til noget i retning af Forebyggende lytning – handler netop om sirener verden over, for Satz har gennem hele syv år filmet i områder, hvor sirenen spiller en afgørende rolle – fra Chile og Holland til Palæstina, Israel og atomulykkesområdet i Fukushima i Japan. En længere sekvens foregår sågar på en amerikansk sirenefabrik, hvor sirener findes i alle former og farver og til tider nærmest ligner moderne kunstinstallationer.

Frem for blot at have optaget sirenernes reelle lyd har Satz inviteret en række lydkunstnere og musikere til at skabe alternative sirenelyde – prominente personager som Laurie Spiegel, Moor Mother, David Toop, Maja Ratkje, BJ Nilsen samt ikke mindst Kode 9, der under sit jordiske navn Steve Goodman faktisk har skrevet en brillant bog om lyden af krig, Sonic Warfare. »Behøver en alarm være alarmerende?« spørger Satz, og sirenekompositionerne i filmen er generelt både abstrakte, skurrende, poetiske og ildevarslende. Det er alle som én gennemkomponerede lydsymfonier, som vel at mærke alle er skabt før filmens billedside.

Og man kan virkelig mærke, at øret på den måde har dikteret, hvad øjet ser, for Satz’ film er et audiovisuelt filmdigt, hvor lydcollagerne, udvalgte interview og digtoplæsninger smelter raffineret sammen med de stemningsmættede billeder. Enkelte gange bliver en reallyd fra optagelserne brugt som del af de sfæriske lydflader – eksempelvis når en kirkeklokke i billedet slår i takt med en lydkomposition – og det kunne Satz egentlig godt have leget endnu mere med, for det knytter filmens forskellige oplevelseslag sammen på overrumplende vis.

Men generelt er filmen et både dragende og skræmmende sansetrip, og i en tid, hvor krig og undtagelsestilstand er del af vores allesammens hverdag, er det en tankevækkende og intens film på talrige niveauer. Man mærker, hvad der sker med én, når ørerne er i alarmberedskab. Når lyden redder liv og varsler død.

An injured swan lies buried in seaweed in a corner of the hall, while four lifeless bodies are scattered across the floor. More seaweed hangs from the ceiling, and the smell hits us already as we step through a bluish, latex-like curtain. The foyer was filled with heaps of seaweed and leftover plastic, and now we are inside an unfamiliar underwater landscape. The bluish light flickers on the wall, the soundscape murmurs faintly like a distant current of noise. We are underwater.

Slowly, bodies come back to life. They stretch in movements of suffering, stagger, struggle – but they rise. Subtle beats and Mads Emil Nielsen’s restless drones push the scene forward. The question of what has happened is rhetorical: everything points to climate catastrophe. Roskilde Fjord has overflowed its banks. Humans continue – despite a state of emergency, despite the flood – while the swan has succumbed.

The dystopia comes alive as the dancers, with impressively exploratory movements, search for ways to adapt to a new world. Here scenography, light and dance interact powerfully, and the senses are overwhelmed. That is precisely why it is a pity that the sound quality feels flat, when the sonic dimension plays such a role in the storytelling.

Still, Vi fortsætter... (We Continue…) succeeds in creating a universe that is at once absurd and all too recognizable. It recalls a gentler version of Ruben Östlund’s Force Majeure: the comic and tragic traits of human nature set against the inexorable forces of nature.

In the end, the dancers leave the stage and we are left in silence – with the afterthought of why we continue like this, and with the sensation of treading water long after leaving the fjord’s flooded universe.

English translation: Andreo Michaelo Mielczarek

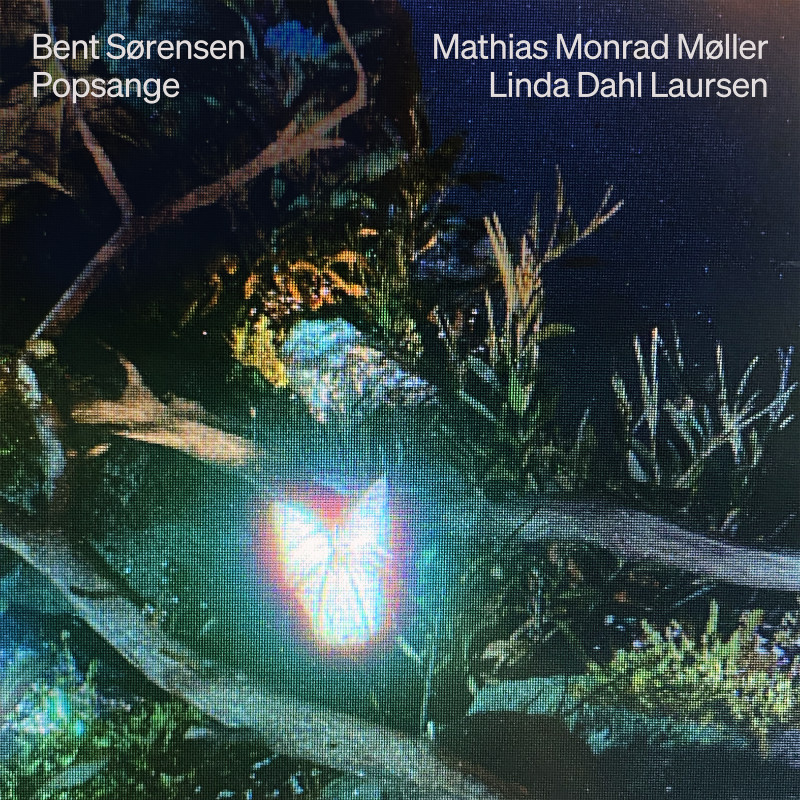

»Your eyes are in reality luminous tunnels to another reality.« So goes one of the key lines in the opening song of Bent Sørensen’s song cycle Popsange, inspired by texts by Michael Strunge. It sets the tone and points toward the recurring lyrical themes: all-consuming love, the shared journey toward another place – and the eyes, always the eyes, appearing in almost every single song.

Mathias Monrad Møller sings with great sensitivity, bringing the text to life, and his interplay with Linda Dahl Laursen is strong. Yet Popsange has much more in common with lieder than with actual songs – not least because of the text’s at times highly poetic language. The tender, almost naïve voice of the lyrics receives its most convincing counterpoint from the piano, as in »Illusion«, where it first follows and supports the words, only to break out into rapid, dissonant chords that interrupt and almost mock the singer.

Still, traces of pop music can be found here and there. »Tid og rum« builds on repetitions with small variations, much like the verses of a pop song. And in »Hjertestrøm«, Møller colors his voice with a timbre that could easily fit on a pop album – not least because the piano here is delicate and playful, giving the voice more freedom.

All in all, Popsange is a pleasant listening experience, but I miss the presence of David Bowie and Lou Reed on the musical front. The work is at its most innovative where it dares to embrace pop. Imagine if the texts had been carried by actual verses, hooks, and choruses – elements that might have turned them into true earworms.

English translation: Andreo Michaelo Mielczarek

On Kaikō – the trio Treen’s second release – saxophonist Amalie Dahl, pianist Gintė Preisaitė, and percussionist Jan Philipp demonstrate confidence, mutual trust, and a distinct musical adventurousness. The opening track »Hylē« unfolds with rattling percussion and strikes seemingly aimed directly at the piano strings, stumbling forward over an underlying drone. The saxophone cuts in with phrases that sound at once admonishing and bewildered. Nothing feels meticulously calculated; instead, the music is carried by a keen awareness of the three musicians’ individual voices within the shared soundscape.

The same basic formula unfolds across the album’s three other pieces, yet always in new variations. On »Kinetic«, Dahl’s saxophone emerges with much greater weight, its slowly growing crescendo mirrored and challenged by Preisaitė’s piano. Improvised music can often slip into polite holding patterns, with the musicians taking turns in the spotlight – but not here. Dahl, Preisaitė, and Philipp appear as three drifting islands without anchors, propelled by their own currents yet inexorably drawn in the same direction. The result is both sudden shifts and an organic flow that can pull the listener into a trance, if one surrenders and simply lets the sound wash over.

It is precisely the trust between them that allows the three to play freely, without fear of leaving or losing each other. In doing so, they create a momentum that is hard to resist – whether one chooses to let the islands drift past or to float along in their current.

English translation: Andreo Michaelo Mielczarek

The first time I heard the title of this opera, I was reminded of Franz Kafka’s grotesque short story In the Penal Colony (1914–19), in which a prisoner is sentenced to have his punishment – a moral admonition – engraved into his skin, after which he is meant to feel what it says. In Written on Skin, which premiered in 2012 and has quickly become something of a modern classic in opera houses around the world, the writing on the skin is instead the caress of a young illustrator, who in reality (!) is an angel. The story is set in the 13th century and appeared in Boccaccio’s collective narrative The Decameron in the following century, but it could just as well take place in a dystopian future.

In a land ravaged by war, violence, and terror, the illustrator is hired to create a book for a tyrannical and ultra-violent lord who, among other things, regards his wife’s body as his own private property. The illustrator/angel, however, enters into a passionate relationship with this wife, and all hell breaks loose. Naturally, they both die, and the lord is left alone with his bitter, useless victory, while the angel is resurrected and thus becomes the true victor – and perhaps a queer figure, as the voice type (countertenor) might suggest.

The Royal Danish Theatre’s production is highly convincing. Benjamin’s music roars and crashes, yet is at the same time curiously hushed in its markedly economical use of means. It is as hard as steel forks magically bent again and again, while the often very powerful volume inscribes itself onto the skin of the eardrums in silken script.

English translation: Andreo Michaelo Mielczarek

»Music to me is – having spent a lot of time listening, composing, and thinking about it – still, essentially, a mystery.«