The im/mediate noise

Abstract

Abstract

Sound has been argued to be a more immediate mode of perception, affording a methodology of understanding distinct from that which has been shaped and cultivated by visuality, the latter often linked with the totalising and objectifying tendencies of the Western rational subject and knowledge. It might be framed as more embodied, affective, and experiential. But what about some of the other qualities of sound, such as the way it eludes the linguistic register and operates on the peripheral? Given the claim of the sonic to immediacy and immersion, how does it figure as a ‘medium,’ especially within scholarship on mediation and technology? How might sound be utilised in an age governed by the disciplinary logic of information and communication technology (ICT), a field and way of thinking that perhaps link the objectification of the visual with the tacit operations of the sonic? This paper seeks to explore digital media polemics in relation to the usage of sound in ‘algorithmic culture’, and to examine sound’s relationship to immediacy and mediation, via scholarly writings from the fields of sound, digital media, technology, and art, and it concludes by looking at the author’s most recent sound installations.

Introduction

As early as 1976, Jacques Attali had argued that, contrary to the focus Western thought has placed on vision, it is through the sonic that one comprehends the world. Vision had been linked to a totalising tendency, abstracting phenomena into decontextualised statistics. Noise, on the other hand, is what permeates all, and offers an alternative understanding. In Listening to Noise and Silence, Salomé Voegelin (2010) opens with a similar dichotomy. Likewise, she defines visuality as a drive for total and objective knowledge/truth, a propensity afforded by the ‘gap’ between the seeing subject and the seen object. On the other hand, aurality possesses no such gap, for hearing is everywhere, and the sonic offers a more contextual and inter-subjective methodology. For her, “sound […] is always the heard, immersive and present” (Voegelin, 2010, p.xiv). Unlike the seen object, which is purportedly stable and cohesive, the heard is constantly unfolding in time, dynamic and contingent, allowing listening to function as a generative and active mode of apprehension. As she describes the act of listening, Voegelin reminds us that sound is perpetually present, shaping reality, regardless of our conscious perception: “listening produces a sonic life-world that we inhabit, with or against our will” (Voegelin, 2010, p.11). Sound, for her, is pure experience, phenomenological and beyond the linguistic and rational order, which is signified by visuality. Frances Dyson makes a similar point in Sounding New Media, noting that “sound is the immersive medium par excellence” (Dyson, 2009, p. 4), and that its distinction from visuality negates the Western binary of subject and object. It is sound’s claim to immediacy and immersion that I wish to focus on for this paper.

Voegelin’s contention rests on a polarised understanding of vision as passive and distant analysis, and the sonic as active, embodied and immediate. While I appreciate her formulation of the sonic subject as an experiential mode that resists abstracting rationality and challenges a visual (by extension, administrative and capitalistic) dogma, I have three issues with this distinction. First, it presupposes the possibility of separating the visual from the sonic, and ignores the existence of media such as film and digital media. Second, it possibly overlooks much scholarship that has taken place within art history and cultural studies that has centred around questioning the visuality perpetuated by the dominant ideology (such as those outlined by Martin Jay in Downcast Eyes), as well as maxims of postmodernism that all meaning is contingent. Third, unlike Attali, she does not acknowledge the danger of the sonic methodology becoming appropriated as a tool for the dominant power regime, despite her conceding that “every sensory interaction [is] always already ideologically and aesthetically determined” (Voegelin, 2010, p.3).

This paper has no intention of reifying the binary forged by the sound scholars noted above between the sonic and the visual, but uses it as a springboard for further discussion. Navigating through two scholarly directions, specifically media and technology theory on the one hand, and critique of post-Fordist immaterial capital on the other, the paper seeks to explore the ways in which some of sound (and other media)’s qualities may be implicated in the wider operation of contemporary information capitalism, and offers the presence of noise/medium as a subversive tactic (noise defined here not in the sonic sense, but rather in the information sense), a specific form of deviation, remainder, and undesirable excess in the capitalist machine – something that philosopher Michel Serres would refer to as ‘parasite’. The paper concludes with a look at two of the author’s most recent sound installations, not as empirical evidence or application of the theoretical stance proposed by the paper, but rather simply as examples of the author’s engagement with some of the ideas to be outlined below.

Algorithmic Culture

Speaking of the imperative to focus on noise, Attali contends that “its appropriation and control is a reflection of power, that it is essentially political” (Attali, 1985, p. 6). As an artist and scholar whose primary interest and practice lie in digital media criticism and sound installations, I would suggest that his proposal is especially timely in the contemporary age, where the legacy of cybernetics and information theory is the dominating logic, realised as the post-human capitalist enterprise of data-mining and algorithmic quantification – what cultural theorist Ted Striphas (2015) has termed “algorithmic culture”. Various media scholars have utilised different terms for framing this state of affairs, such as cognitive capitalism, the knowledge economy, the attention economy, etc. For Jodi Dean (2005), the term is “communicative capitalism”, designating a state where communication is a commodity, rather than a liberating act of agency. Maurizio Lazzarato (1996) articulates a similar idea in his theorisation of immaterial labour, and argues that communication and other social and cultural acts are now subsumed under the production circuit. Matteo Pasquinelli (2009) has also outlined in detail the ways in which Google’s PageRank algorithm leverages the population’s general intellect and capitalizses on users’ attention and knowledge. Nicholas Carr (2012) has described this system as “digital sharecropping”, Web 2.0’s core means of value-extraction, which exploits the free labour provided by the masses by granting them the means of production but then retaining rights over that which they produce, accumulating economic surplus for the providers of such ‘tools’ and platforms, while ensuring that the labourers do not see themselves as working, but rather as ‘users’ who are socialising.

The assumption underscoring all of this is that being may be cognizable by undergoing codification. For Striphas, ‘algorithmic culture’ involves the conversion of all patterns of relations, expressions, associations between objects, people, locations, and ideas, into quantifiable informatics. As media theorist, philosopher, and programmer Alex Galloway has suggested, “informatics is what Marx would have called a real subsumption […] of the visual […] espiteme handed down from the Enlightenment” (2007), referring specifically to the relation between seeing, reason, and knowledge, and drawing this line of thinking all the way to software development and algorithm deployment. Galloway’s formulation echoes the distinction outlined by Attali and Voegelin, linking visuality, totalising knowledge, decontextualisation, numeric quantification, and cybernetic control. But what role does sound play in this information-political landscape?

Medium / Mediation

In the essay “Noise and Exceptions”, Stephen Crocker (2007) opens with the observation, following Jay Bolter and Richard Grusin’s double logic of ‘remediation’, that our innovations and advances in media have always been driven by an intention to be more immediate, leading to a paradox whereby the more we try to escape mediation (the same way that a painting or virtual reality or video conferencing efface themselves to achieve realism and presence), in order to be more immediate with the content (thoughts, reality…etc.), the more mediated we become. He urges for a McLuhanesque focus on the medium itself, “the process of making a means visible” (2007). Drawing from Michel Serres, Crocker goes on to emphasize the persistence and ineradicability of the medium. Utilising communication between a sender and receiver, he illustrates how the conception of a perfect signal transmission is impossible (something that mathematician Claude Shannon had already noted in his landmark paper on information theory in 1948), that the noise of the medium always exists, and that immediacy is an illusion. As he argues, “the medium in which our actions take place affects what we can be and do” (2007). The medium, then, exhibits particular qualities, here conceived by Serres as the ‘noise’ in signal-processing. “We can never eliminate the space of transmission. There is always a context of communication,” he writes. This emphasis on the persistence of the medium and its effect being a significant feature to be examined, is rendered evident when he says, “the user is used by the medium” (2007).

Talking about a specific form of mediation – technology, media ecologist Neil Postman has noted that “technologies change what we mean by ‘knowing’ and ‘truth’; they alter those deeply embedded habits of thought which give to a culture its sense of what the world is like” (Postman, 1992, p. 12) and that “embedded in every tool is an ideological bias” (ibid., p. 13). This is very much the focus of philosopher Andrew Feenberg’s (1999) book Questioning Technology, where he illustrates how technologies are not neutrally self-determined and autonomous entities, but rather they are imbued with very specific socio-political implications and intentions right from their conception. As the critical pedagogue Ivan Illich says, “surrounded by omnipotent tools, man is reduced to a tool of his tools” (Illich, 1971, p. 165).

So what about sound, if one considers it a medium, and a technology?

Sound as Mediation

While philosopher Bernard Stiegler’s (1998) writing has been used by proponents of post-humanism, it might be helpful here to think about his idea of ‘originary technicity’, the idea that humans have always been technological and mediated. Taken with the arguments of the medium by Crocker and Serres, one can propose that sound (or aurality, to be specific), too, is a form of mediation, and that immediacy and mediation are not mutually exclusive, but are simultaneous qualities of sound. As Dyson notes, “audio has naturalised […] the disembodying effects of new media technologies, and […] paved the way for further mediation” (Dyson, 2009, p. 3). Even if one concedes, for the moment, that there is indeed some distinction between visuality and aurality, and that sound is more immediate than sight, what is the cost of this ‘immediacy’? How does it function simultaneously, as mediation?

As Dyson notes, “immersed in sound, the subject loses itself” (Dyson, 2009, p. 4). In 2015 I attended a conference on Jacques Lacan and psychoanalysis at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, and one speaker, Alois Sieben, talked about the character of Samantha, the operating system, in the movie Her by Spike Jonze, and how she successfully occupied an ambivalent and entangled space between the human and non-human, using the humanness of her voice. However, for me, what was more intriguing was how Samantha’s voice signified the phenomenon of how sound is being used to condition, control, and indoctrinate the population, through its expert deployment and complicity in creating an immersive and ‘interactive’ everyday experience. Speaking of adapting Samuel Beckett’s work for film, artist Stan Douglas writes that “the advent of the sound film is exactly contemporary with […] its formalisation of how a new cinematic space would be constructed” and that “these innovations made it possible for a film to yield a greater impression of subjective experience” (Douglas, 1988, p. 16). This ongoing quest for further, deeper, more realistic immersion, which sound assists in constructing, is precisely what many scholars are wary of. In a chapter titled “What Does Simulation Want”, Sherry Turkle answers her own question by proposing that “simulations want, even demand, immersion” (Turkle, 2009, p. 6) and that “simulation makes itself easy to love and difficult to doubt” (ibid., p. 7). There has been much development in cultural studies, art history, visual culture, film studies, and other disciplines in the humanities for the past century focusing on visuality and semiotics in the examination and criticism of popular culture, mass media, language, colonialism and capitalism. Sound had been referred to in the context of mass media, its role in creating propaganda and advertisement obliquely acknowledged (here I am thinking mostly of the Frankfurt School), but much more emphasis has been placed on the visual. I would argue, in the contemporary context of the ubiquity of information and communication technology (ICT), that sound plays a crucial role in creating a fully technologically-dependent and machine-governed existence. Sound design, sound effects, sound cues, phone messages, phone voices, voice recognition, ringtones, notifications, etc.; an entire society undergoing a Pavlovian experience. Contrary to thinking about Samantha’s voice as a machine-becoming-a-Subject, I am more interested in thinking about another character played by Scarlet Johansson, that of the alien in Under the Skin, who, in the beginning of the film, ‘practised’ speaking by making various fragmented phonetic sounds, training herself to abduct humans: the voice as a technology, and in this case, a tool for colonisation.

As an addendum to this thought, a few days after the above conference I received a phone call where I did not realise until a minute in that I was speaking with a machine. The programme was expertly engineered to emulate a real person, with pre-recorded messages and a sophisticated word-recognition software programmed to respond intuitively to all my answers. It was not until I became irate and snapped at the ‘telemarketer’ that the program malfunctioned, exposing its opaque machinic self, by replaying certain segments of the pre-recorded phrases. Perhaps this is the cost of immersion and immediacy.

How might artists cultivate spaces for alternative understandings and resistance?

Techné, Art, and Noise

In The Question Concerning Technology, Martin Heidegger (1977) discusses in depth technology’s propensity for constructing worldviews by tracing the etymology of the concept to techné, the activities of craftsmen and artists. He contends that while traditional technology is meant to reveal and bring forth, modern technology – through the process of gestell (enframing) – constitutes an apparatus that positions the world into a particular order of revealing: that of the standing-reserve. As Heidegger notes, enframing “banishes man into that kind of revealing which is an ordering [and] where this ordering holds sway, it drives out every other possibility of revealing” (Heidegger, 1977, p. 27). This particular construct induces an understanding of the world as discrete and calculable blocks, as marketable resources, as capital, ready to be abstracted, ordered, and privatised. Emphasising that technology is not driven by rational functionality, Feenberg follows Bruno Latour in noting that “technical devices embody norms” (Feenberg, 1999, p. 85), and that after certain technological innovations have been black-boxed in a process Latour calls ‘closure,’ the norms and social values they embody become the “unquestioned background to every aspect of life” which “seem so natural and obvious they often lie below the threshold of conscious awareness” (ibid., p. 86). Heidegger’s conception of technology as a deterministic and autonomous entity that seems inherently geared towards control and oppression has been heavily criticised by Feenberg, who approaches the question in a much more considered manner, synthesising the Frankfurt School, postmodern critical theory (i.e. Foucault), as well as thinkers like Latour and other contemporary sociologists. Nevertheless, perhaps Heidegger’s theory has something to offer here in terms of a counter-strategy.

If we accept the aforementioned claims that 1) the medium persists and exerts its own forces, effects, truths, and norms, that 2) sound is also a medium/technology with immediate and mediated qualities, and that 3) the nefarious operations of ICT-facilitated capitalism function, at least partially, through its immersive and clandestine qualities (as do all technologies), then how might artistic gestures be mobilised in response? Here one returns to the paradox of mediation, being reminded once again that immediacy is always already a form of mediation in itself, and that noise will always persist.

In Being and Time, Heidegger (1962) applies his analysis to tools and the two states of readiness-to-hand (Zuhandenheit) and presence-at-hand (Vorhandenheit) to elaborate on the idea of transparency of the medium, noting that a tool only emerges from the hidden operation of readiness-to-hand when it is broken, and becomes presence-at-hand. This suggests that, in the realm of technological mediation, a critical investigation of our relationship to the dominant technology can only occur through the breakdown or displacement of the normative function, such that the medium itself and the state of mediation can be revealed, foregrounded, and emphasised. The concept of examining the medium has similarities to Marshall McLuhan’s (1994) idea that it is the medium itself, usually hidden from users’ awareness, that needs to be examined in order for a critical understanding of its psychological and social effects to be possible. As Terence Gordon explained, McLuhan championed artists to create ‘anti-environments,’ such as James Joyce’s Finnegan's Wake (which, for him, highlighted the inadequacy of print and linear language through unsettling the reader), for their potential in making “a visible environment of media effects intended to jar us awake” (Gordon, 2010, p. 86). This can also be likened to the estrangement effect of the Marxist playwright Bertolt Brecht. A literary device that originated from the Russian Formalists (ostranenie), Brecht took estrangement into a politicised realm of theatre spectatorship in order to self-reflexively break the fourth wall and disrupt naturalised but invisible cognitive and social tropes. By doing so, he aimed to highlight and destabilise the constructed nature of theatre, representation, and by extension, meaning and society (Foster et. al, 2004). This language of examining the hidden mechanisms of technics is reminiscent of Latour and Feenberg’s argument noted above. Like Heidegger’s notion of presence-at-hand, the medium only becomes visible and transparent for consideration when something out of the norm has occurred, such as breakdown of its intended function (in this case, immersion, identification, illusion), accentuating the device.

Similarly, in calling for an unveiling and breaking of the illusions normatised by reigning modes of mediation, Feenberg also proposes that “a critical theory of technology can uncover […], demystify the illusion […], and expose the relativity of prevailing technical choices” (Feenberg, 1999, p. 87). Although he only suggests an investigation from a social sciences perspective, and does not mention art, his theorisation of the necessity to examine the ‘technical codes’ that have become invisible and self-evident, can be very beneficial in thinking about a strategy and space where this alternative thinking can occur.

In an essay titled “Noise versus Conceptual Art,” improvisation musician Mattin lists several characteristics of noise, one of them being that “noise exceeds the logic of calculability” (Mattin, 2010), and that it operates in opposition to capital. As Crocker (2007) reminds, the medium, the noise, always persists in signal-processing. If noise is an ‘other’ to signal, as Joseph Nechvetal (2011) notes in his book Immersion into Noise, then it is through noise that one should begin to formulate a strategy of countering the signal-processing of communicative capitalism.

So, is the role of the artist to reveal the medium/technology through noise? At the conference Sound Art Matters held at Aarhus University in 2016, Jamie Allen and Morten Søndergaard spoke about the idea of revealing. Unlike some scholars, such as Heidegger, who believe that revealing/transparency is imperative, Allen is of the opinion that revealing alone is not enough, and to counter what he calls the infrastructure (or perhaps ‘protocol,’ in Galloway’s terms) one needs to engage it directly, to couple, to modulate, and to generate new information. I can agree with this perspective, especially in the wake of Snowden. The general public seems to be living in a state of outraged passivity; surveillance is common knowledge, but beyond agreeing that it is ethically suspect, it does not automatically lead to widespread public unrest and demand for change. An artistic operation that focuses solely on revealing may be accused of ignoring the persistence of mediation, in presuming that there is, beneath all the layers and after all the phenomenological bracketing, an authentic and unmediated truth or essence to be revealed, and once that is done, oppression ends and a process of subjectivisation ensues. Furthermore, Jodi Dean has pointed out the irony in the use of transparency rhetoric of by the ICT industries to justify the incessant digging for information, so that we may at some point reach the democratic utopia of full publicity, “the ideology of technoculture” (Dean, 2003, p. 101). However, I do also wish to express support and admiration for hacktivist groups such as Anonymous and Wikileaks, and also believe in the potentiality and significance of simply revealing information that was hidden, in the important tradition of artists such as Hans Haacke and Mark Lombardi. That being said, the proposed tactic is not merely a call for transparency of the machine, as many interpret Heidegger and Brecht; what I am suggesting is rather a form of revealing beyond simply the revealing of information (ie. Wikileaks) or revealing as information (ie. techné), but rather one characterised by the production of something that exceeds the discrete unit, through an appeal to the medium’s persistence.

Commenting on artist Char Davis’ practice of virtual reality-based work, media art historian Oliver Grau also speaks to the danger of immersion when he says that “the more intensely a participant is involved […] the less the computer-generated world appears as a construction.” (2003, p. 200) And he goes on to caution that the apparatus of VR, with the aid of audio, effectively hides itself from scrutiny, creating a lack of distance which is needed to critically analyse art. “Immersion is produced […] when the message and the medium form an almost inseparable unit, so that the medium becomes invisible.” (2007, p. 148) But if one follows the arguments noted above by Crocker, Serres, and Stiegler, then this lack of distance is an illusion, as the medium of VR itself still exists. The imperative, therefore, is not to advocate for some mythical objective outsider’s critical analysis, but to expose and examine the medium, while understanding that we are always mediated. Grau seems to point to this obliquely when he says that “obviously, the relation between critical distance and immersion is not a simple matter of either-or.” (Grau, 2007, p. 154) Art educator Maxine Greene’s (2001) theorisation might be helpful here, as she insists on the simultaneous different phases of the experiential and the detached knowing (or, the immediate and the mediated).

Recent Work

As attempts to engage with the explicated ideas above, I will briefly talk about two recent sound installations, both funded by the Canada Council for the Arts Media Arts program.

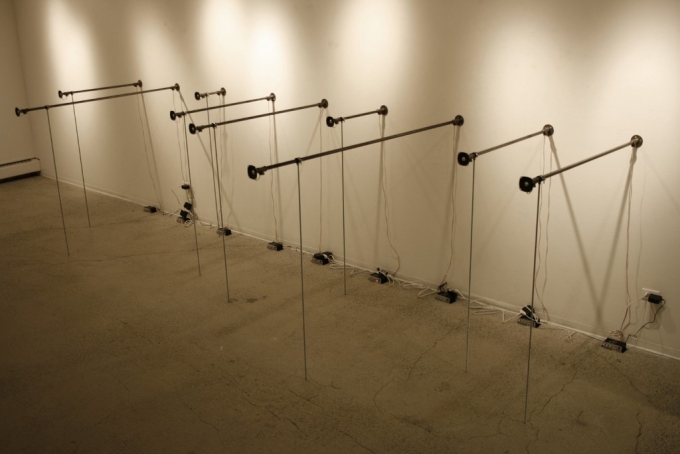

The first project, titled sonic prostheses, was completed in late 2014. Taking the form of a spatial bar graph, the sound installation utilises sound recordings of user-computer interaction and the sculptural form of bar graphs to scrutinise the ubiquity of machine administration/quantification through the data-mining of users.

It consists of 9 steel pipes (placed roughly 4’ apart) protruding out from the wall in various lengths. A speaker is mounted at the end of each pipe. Playing from each speaker are sound recordings of computer-usage from a group of users, such as keyboard-typing, mouse-clicking, chatting, gaming, streaming, etc. These recordings have been quantified according to a set of personal measurements determined by myself, and the results are reflected by the lengths of the pipes. The categories of measurements were intentionally arbitrary, nonsensical, and situated, ranging from whether the artist ‘likes’ the voice of a user to how satisfied with their life the artist thinks the users are. The artist, in turn, takes on the role of the ‘analytics,’ a fact that is more significant than the specific qualities being ‘measured.’ The result becomes a counter-graph, where the categories measured by the artist are not of conventional marketing use, but are idiosyncratic and based on spontaneous arbitration, inducing an obsolescence that becomes a disruption of capitalist signal-processing.

In this way, each user has been profiled through the data derived from their computer-usage, emphasising their reduction to just an indicator on a graph, disembodied and anonymous. The capitalist process in which all cognitive/social attributes are subsumed into the production circuit is made ostensible through the representation of each user as a pathetic and minimal Beckettian humanoid, constituting part of larger statistical graph, repeating through the mouthpiece only the sounds of digital immersion and mediation, simultaneously. There is perhaps a resemblance to the play Not I by Becket, where all the viewer can see and hear is a mouth spouting out some barely intelligible speech very rapidly, highlighting this unfathomable desire to keep communicating, to keep disclosing information. In this case, sound is used on several levels: as an indication of the computer-user relation, as a quality utilised to measure and represent subjects, and as an index of the body, fully complicit in the operation of capitalist abstraction and digital immersion.

Like some of my previous work, this installation seeks to emphasise both the disembodied nature of reducing being to information for instrumental purposes, as well as the persistence of the medium/body/noise, what Crocker calls ‘medial noise,’ through a deliberately embodied spatial installation and obsolescence. As Galloway has said, the human body is “the most emblematic media system” (Galloway, 2012, p. 9). In this case, the audience will be able to experience the graph spatially, walking in between the pipes/humanoids, with the lengths corresponding to the quantified traits of the users, and the speaker acting as both the last remnant of their bodies, as well as an insistence on the presence of the medium/body in general. The noise ruptures through via a deliberate exacerbation of the quantification machination, an emphasis on foregrounding the medium, but also through a deviation from its normative function, a role reversal in which the artist becomes the analytic, and the quantifying function is rendered obsolete.

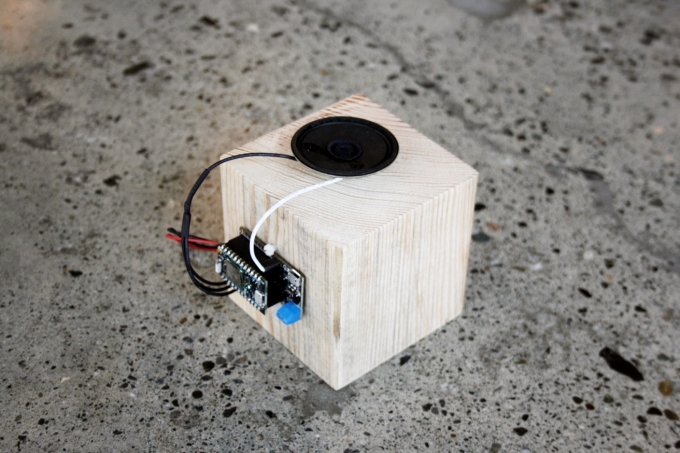

The most recent project, before z axis (feedback loop of commensuration), is a large floor-based interactive sound installation that spans roughly 30’ by 30’ and consists of 49 small 4” by 4” wooden blocks composed in a 7 by 7 grid, placed roughly 4’ apart. Situated on each block is a speaker unit consisting of a micro-controller, a battery pack, and speaker. A computer and a webcam are situated on the side, collecting and measuring certain traits from the audience members. Like the previous project, the exact data to be extracted (most likely traits such as density, movement, and height) is less relevant than the act of extraction itself. The calculated result from the data-mining will take the form of X and Y coordinates, which are transmitted by the computer wirelessly to one of the speaker unit blocks, plotted on the grid via sounds emitting from the speakers. This process repeats every thirty seconds to a minute as audience members walk through the installation, continuously having their data collected and directed towards various coordinates on the grid.

In such a way, the viewers/users experiencing the piece will be subjected to the compulsory and clandestine operations of surveillance and the machinic abstraction of distilling human subjects to quantifiable traits that will come to determine their identity, regardless of how decontextualised and inadequate this process may be. The grid, like the bar graph above, comes to stand in as an emblem of ICT and its capitalist function. As the machines calculate and represent the users by mapping their data on the grid, the users’ own bodies are being mapped as well, as they navigate the grid to locate their own ‘coordinates’, where the sound will be emitted. Through the process of experiencing the piece, the users’ bodies become abstracted and reduced to a single node on the grid, while they themselves are spatially mapped on the grid as well, repeatedly, as they navigate through the piece. The process emphasises the ways in which they ‘become’ the data that has come to represent them, blurring the line between subjects and their data representation. In this sense, technological knowing, machinic abstraction, and data-based representation all mediate the users through an ever immersive and immediate operation, facilitated by sound, attesting once again to sound’s simultaneous properties of immediacy and mediation.

My work is often influenced by the linguistic and existential absurdity of Beckett. This project attempts to create a Beckett-esque scene in which subjects without agency navigate a nameless space monotonously and repetitively. Through pushing certain elements of the contemporary human condition to the extreme and minimal, the work of Beckett utilises a strategy that Gilles Deleuze (1971) characterises as a method to reveal the vacuousness, absurdity, and political agendas of normatised underlying structures. In a similar vein, this project intends to spatialise a minimal form of quantification – that of a grid – while capturing information from the viewers and inducing them to navigate the space in a way that might resemble de-subjectified humanoids wandering through a maze akin to lab mice, repeatedly towards their coordinates, their data representation. The sounds might induce a Pavlovian response where viewers are compelled and summoned to voluntarily approach the source, foregrounding the agency that communication technology has in determining and priming human behaviours/responses. Once again, the medium of algorithmic culture, of ICT-facilitated capitalism, is foregrounded for scrutiny, while its function is displaced in an absurdist exacerbation in which what emerges is not instrumental signals, but a surplus of dysfunctional non-information (or, new information): noise. In creating a situation in which the viewers wander about a grid chasing their data in the form of generic beeping sounds, the installation will attempt to highlight the contemporary phenomenon of surreptitious yet coercive data-mining, the alarming prevalence of data-based representation, and, as this paper attempted to demonstrate above, the fraught relationship between sonic immediacy and the potentially subjugating mediation.

Conclusion

The paper has attempted to sketch an examination of sound’s claim to immediacy through a reading that combines media and technology theory and socio-political concerns of the digital, via cultural theory and post-Marxist thoughts, and proposes noise as an artistic tactic that deviates from the normative function such that the apparatus may be foregrounded and examined. Sound’s currency via its claim to immediacy, embodiment, and the experiential is questioned by examining its potential complicity with the operations of algorithmic culture and digital immersion, fuelled by an understanding through techné. The simultaneous immediacy and mediation are argued to be characteristic of all media/technology, including sound and sight, and the paper challenges sound’s privileged position against visual rationality and totalisation. The proposed artistic tactic for dissent is not simply to celebrate sound’s formal claims but rather to lean on the noise of the medium, noise as that which is inherent to the medium and facilitates slippage from the dominant mode of being and knowing, allowing the normative machination to be revealed such that an alternative mode may emerge and new or counter-information may be produced. There is a need to acknowledge the accusations of technological determinism when referencing Heidegger and McLuhan, as well as the descent of Brecht’s currency on the political aesthetics hierarchy. (Whether or not these may be reasonable arguments will need to be taken up elsewhere). Like other scholars, I too view ‘transparency’ as a narrow-sighted argument to offer within the polemics of technology and media criticism. However, my reading of the above scholars does not limit their contributions to a simple call for ‘revealing’ the machine, but rather one for possibilities of the alternative, through a focus on noise, the ‘other’ of the information-capitalist assemblage.

Keywords

Bibliography

Alsina, P. and Galloway, A. (2007) “We are the gold farmers”, Culture and Communication. Available from: http://cultureandcommunication.org/galloway/interview_barcelona_sept07.txt [4 November 2016].

Attali, J. (1985) Noise: the political economy of music. s, Minneapo: University of Minnesota Preslis.

Bolter, J. D. & Grusin, R. A. (1999) Remediation. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Carr, N. (2012) The Economics of Digital Sharecropping, Rough Type, blog post, 4 May. Available from: http://www.roughtype.com/?p=1600 [1 May 2016]. Crocker, S. (2007) Noise and Exceptions: Pure Mediality in Serres and Agamben, C Theory. Available from: http://www.ctheory.net/articles.aspx?id=574 [4 November 2016].

Dean, J. (2003) Why the Net is not a Public Sphere. Constellations, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 95-112.

Dean, J. (2005) Communicative Capitalism: Circulation and the Foreclosure of Politics. Cultural Politics: an International Journal, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 51-74. Deleuze, G. (1971) Masochism: an interpretation of coldness and cruelty. New York: G. Braziller, New York.

Douglas, S. (1988) Goodbye Pork-pie Hat. In C. Coolridge & S. Douglas, (eds.), Samuel Beckett: Teleplays, pp. 11-19. Vancouver: Vancouver Art Gallery

Dyson, F. (2009) Sounding new media: immersion and embodiment in the arts and culture. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Feenberg, A. (1999) Questioning technology, Routledge. New York: London.

Foster, H., Krauss, R., Bois, Y., & Buchloh, B. (2004) Art since 1900. London: Thames & Hudson.

Galloway, A. R. (2012) The interface effect, Malden, MA: Polity Press.

Gordon, W.T. (2010) McLuhan: a guide for the perplexed. New York: Continuum.

Grau, O. (2003) Virtual art: from illusion to immersion,Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Grau, O. (2007) Remembering the phantasmagoria. In O. Grau, (ed.), Media Art Histories, pp. 137-161. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Greene, M. (2001) Variations on a blue guitar: The Lincoln Center Institute lectures on aesthetic education, New York: Teachers College Press.

Heidegger, M. (1962) Being and time, New York: Harper.

Heidegger, M. (1977) The question concerning technology, and other essays, New York: Harper & Row.

Illich, I. (1971) The dawn of Epimethean man. Iin B. Landis & E. S. Tauber, (eds.), In the name of life: Essays in honor of Erich Fromm, pp. 161-173. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Lazzarato, M. (1996) Immaterial labor. In P. Virno & M. Hardt, (eds.), Radical thought in Italy: a potential politics, pp. 132-147. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Mattin. (2010) Unconstituted praxis. Brétigny-sur-Orge: CAC Brétigny.

McLuhan, M. (1994) Understanding media: the extensions of man. Cambridge, Massechusets: MIT Press.

Nechvatal, J. (2011) Immersion into Noise, Ann Arbor: Open Humanities Press.

Pasquinelli, M. (2009) Google’s PageRank algorithm: A diagram of cognitive capitalism and the rentier of the common intellect. In K. Becker & F. Stalder, (eds.), Deep Search. London: Transaction Publishers.

Postman, N. (1992) Technopoly: the surrender of culture to technology. New York: Knopf.

Stiegler, B. (1998) Technics and time, Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

Striphas, T. (2015) Algorithmic culture, European Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 18, no. 4-5, pp. 395-412.

Turkle, S. (2009) Simulation and its discontents. Cambridge, Massechusets: MIT Press.

Voegelin, S. (2010) Listening to noise and silence: towards a philosophy of sound art. New York: Continuum.