70 Minutes Confined to a Creaking Construction Site

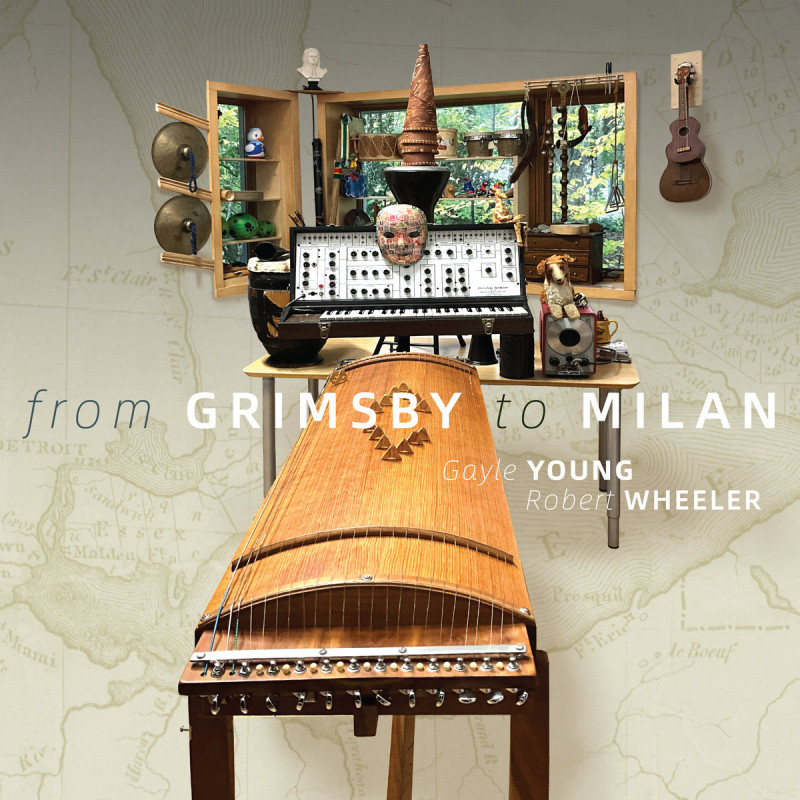

The Amranthen is a peculiar string instrument, invented and built by Canadian instrument maker Gayle Young. It consists of a wooden box fitted with 21 steel strings and three bass strings, and its unique, organic timbre unfolds on From Grimsby to Milan, where Young improvises alongside American musician Robert Wheeler on synthesizer. The recordings from Grant Avenue Studios capture the encounter between the acoustic and the electronic in a loosely shaped, raw musical flow.

Across nearly 70 minutes divided into six parts, the listener is kept in a state of constant uncertainty. The sonic landscape resembles a noisy, dystopian construction site: on »Seaweed Slowly Shifting«, bows are drawn with a saw-like rasp, fingers scratch, machines whirr, and sharp electronic zaps flash like warning lights. Later, bells and pulse-like rhythms enter on »Mariana Trench«, while »Consonant Harmony« slows the pace, settling into a subdued, crackling atmosphere where sparse melodic gestures suggest a momentary lull in the turmoil.

The construction-site metaphor fits well, for the most compelling version of this project would likely be to experience Young’s handmade instruments live, in direct dialogue with Wheeler’s electronics. As an audio recording, however, the project remains closed-off and somewhat insular. And although From Grimsby to Milan contains a wealth of fine detail, the journey – from Grimsby in Canada to Milan in Ohio – ultimately feels long and monotonous, without ever offering the listener the key to unlock its dystopian worksite.

English translation: Andreo Michaelo Mielczarek

New Central American Tales

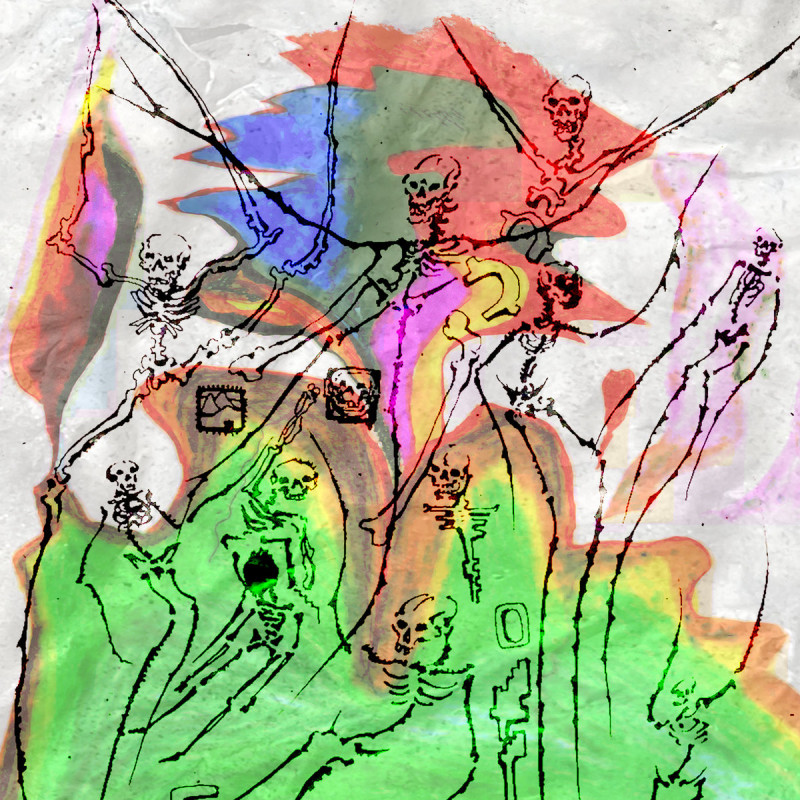

There is plenty of space around the many different sounds and voices narrating Central American horror stories on Honduran-Danish artist Xenia Xamanek’s album Germinate. The words »germinate« and »wilt« appear in the title, serving as fitting markers for the blossoming, bubbling, futuristic, and slightly eerie soundscape. A handful of voices fill the ears with mechanical, intense connections, swirling impressions of nature and language into the brain.

The album is a rare reinvention of the oratorio, the 18th-century religious opera genre featuring sung text fragments and wordless music. A significant departure from the dance floors Xamanek used to curate. Here, singers and an electro-acoustic soundscape tell stories through two simple, word-heavy recitatives, two arias with chanting narration, and electronic soundscapes.

There’s a calmness in Xenia Xamanek’s approach that can become utterly addictive. The material from their ancestral storytelling – and perhaps even the chanting narrative style – sets a scene that feels both warm and familiar. Yet at the same time, it turns original and alien as the calm of the words is challenged by dense patterns of simple sonic elements interacting with each other.

Oratorios in the 18th century lasted three hours and can easily feel distant and irrelevant today. But Xamanek’s album, rooted in the cuentos y leyendas de Honduras they heard in their childhood, offers three-quarters of an hour of presence – one that unexpectedly points forward.

In Complete Silence, We Listened to the Sounds of Outer Space

Saturday night at Huset’s Xenon stage was a true laboratory of sound, body, and technology. Two vastly different artists explored the expressive possibilities within sound and performance art. First, the Icelandic composer Sól Ey presented her performance Hreyfð («she is moved« in Islandic) wearing a suit equipped with microphones, speakers, and gyroscopes, her movements were transformed into sound. Through slow, deliberate motions, Ey tuned into different frequencies. Each gesture created a new auditory universe – ranging from soft, ethereal tones with the finest textures to distorted and aggressive noises, from cosmic whispers to fragmented radio signals that reminded me of NASA’s Voyager recordings. In complete silence, the audience observed Ey as she explored the sounds of outer space.

Afterward, the Japanese drummer Ryosuke Kiyasu stepped forward like a sonic warrior. With nothing but a snare drum, a table, and a microphone, he unleashed a relentless 30-minute sonic assault. He screamed, pounded, and perspired. He used both his own body and drumsticks. The audience held their breath as Kiyasu attacked his snare drum like a man determined to break through the limits of sound from within. And when he finally collapsed onto the floor, the room erupted in cheers.

While Sól Ey wove an intricate dialogue between technology and movement, Ryosuke Kiyasu launched a frontal attack on the material’s resistance. Both confronted the boundaries of sound with uncompromising dedication, demonstrating that sound art is not just about playing – but about transformation.

The Power of Trance: A Journey from Indonesia to Roskilde

In 2022, the Indonesian group Juarta Putra turned the Roskilde Festival upside down and captivated a large audience with a trance dance called reak. In the documentary Cosmic Balance, director Andreas Johnsen takes us back to the time just before, to Putra's hometown of Cinunuk in West Java, Indonesia. Through 24-year-old Anggi Nugraha, we are introduced to reak and how both the young and the old, to the sound of booming drums, distorted tarompet (a reed wind instrument resembling an oboe), and reciting song, surrender to the ancestors who visit them in their wild trances. Anggi himself, who has just become the leader of the reak group, is haunted by his stern grandfather, who orders that traditions must be preserved and upheld.

However, Anggi is unsure about his new role. He is not of the bloodline of the predecessor Abah or any of the other members in the group, but he grew up in the village among the musicians after his parents, for unknown reasons, left him there. We also meet Anggi's girlfriend, whom he wants to marry, but whom he has not received his parents' approval to marry for the same reason. Anggi is a sensitive and sympathetic young man, whom one can only wish the best for. He himself seeks help from a fortune-teller, who gives him the strength to travel to Denmark and to marry his chosen one. How the marriage will turn out is unknown, but the journey to Roskilde is a clear success.

The film's soundtrack works predominantly well with field recordings and the group's own music. Less fitting are the passages with lyrical piano and strings accompanying the trance scenes from Cinunuk, which come across as unnecessarily staged. This does not change the fact that Cosmic Balance gives a sympathetic and fascinating portrait of music that, on the one hand, fits perfectly with the global and diverse profile of the Roskilde Festival, but which also comes from a world so distant from the inferno of Roskilde that one can hardly see where the ends meet. But they do, that night at Roskilde.

English translation: Andreo Michaelo Mielczarek

Community in Collapse

The transcendent takes the front seat on Copenhagen-based Nausia’s latest album, Finding a Circle. Slow builds and intense demolitions form the band’s basic structure, and a web of saxophone harmonies floats through a tight and daring interplay. Not every band manages to preserve the intense feeling of a live concert on a recording. But on Finding a Circle, Nausia succeeds in hammering the gap between stage and studio down to an irrelevant trifle, through a phenomenal and remarkably great-sounding ensemble performance.

There is something about the physical conditions of the saxophone that makes it easy to sense the musician’s presence. The clatter of the keys and the intense breathing make it effortless to form an inner image of the human behind the brass. On the track »E.D Interlude«, the saxophones’ airy exhalations and mechanical flapping ensure that, as a listener, I behave with the same quiet reverence as I would at a concert. So when the next track, »Eco Death«, kicks the door in on the silence, it is hard not to feel almost physically exhilarated by the album’s intense contrasts between presence and destruction.

Titles such as »flowers grow through concrete too« and »Eco Death« cast the wordless album in a bleak light of climate collapse. Finding a sense of community in a chaotic world – whether at a concert, on an album, or elsewhere – is essential to life in a time of crisis. Finding a Circle is a fine example of exactly that.

Caught Between Too Much and Too Little

Electronic musician Amphior, aka Mathias Hammerstrøm, opens on a positive note: »Under the Stars« exudes a Twin Peaks–like melancholic romanticism infused with an unsettling timbre that raises expectations. By the second track, however, it becomes clear that the listening experience will not be quite as positive as one might initially have hoped.

»Time Is a Thief« simply does not impress in the same way. On top of the clichéd ticking clock in the background, neither the piano melody nor the atmospheric elements make much of an impact, stuck in the nondescript middle ground between too much and too little. Unfortunately, this alternation between compelling tracks and more filler-like pieces comes to characterize the release as a whole.

Both »Healing« and »Disappearing« feature strong melodies with a delicate, ethereal, bittersweet melancholy. Like »Time Is a Thief«, »Bloom« also employs a ticking clock as a background element, but to far better effect, as the music above it is much more captivating – not least thanks to Stine Benjaminsen’s (aka Recorder Recorder) clipped vocal samples, which lend the track a welcome sense of strangeness. The release does, however, contain a number of tracks that never manage to leave a lasting impression, no matter how many times one listens. A melody that simply needed a bit more life. An effect that could have benefited from being turned up. It is a shame, because on roughly half of the tracks Hammerstrøm demonstrates that he is capable of creating truly beautiful music.