The Greenlandic word Takkuuk means »attention«, and it is the slightly ironic title of one of the more chaotic projects at this year’s CPH:DOX. The film is a collaboration between visual artist Zak Norman, film director Charlie Miller, and the Belfast-based electronic duo BICEP, and it also features seven musicians from Kalaallit Nunaat and Sápmi. In other words, a multitude of voices and agendas are at play, and the project clearly bears the marks of that.

The process leading up to the film sounds more interesting than the work itself. Norman and Miller travelled around the Arctic, seeking out musicians and researchers while filming glaciers and ice. The film’s seven young musicians then entered the studio with BICEP to create a shared soundtrack: a kind of club-oriented remix of seven very different practices, ranging from drill and heavy metal to joik, throat singing and drum dance. It might have been fascinating to follow those encounters, but instead the film takes us in another direction.

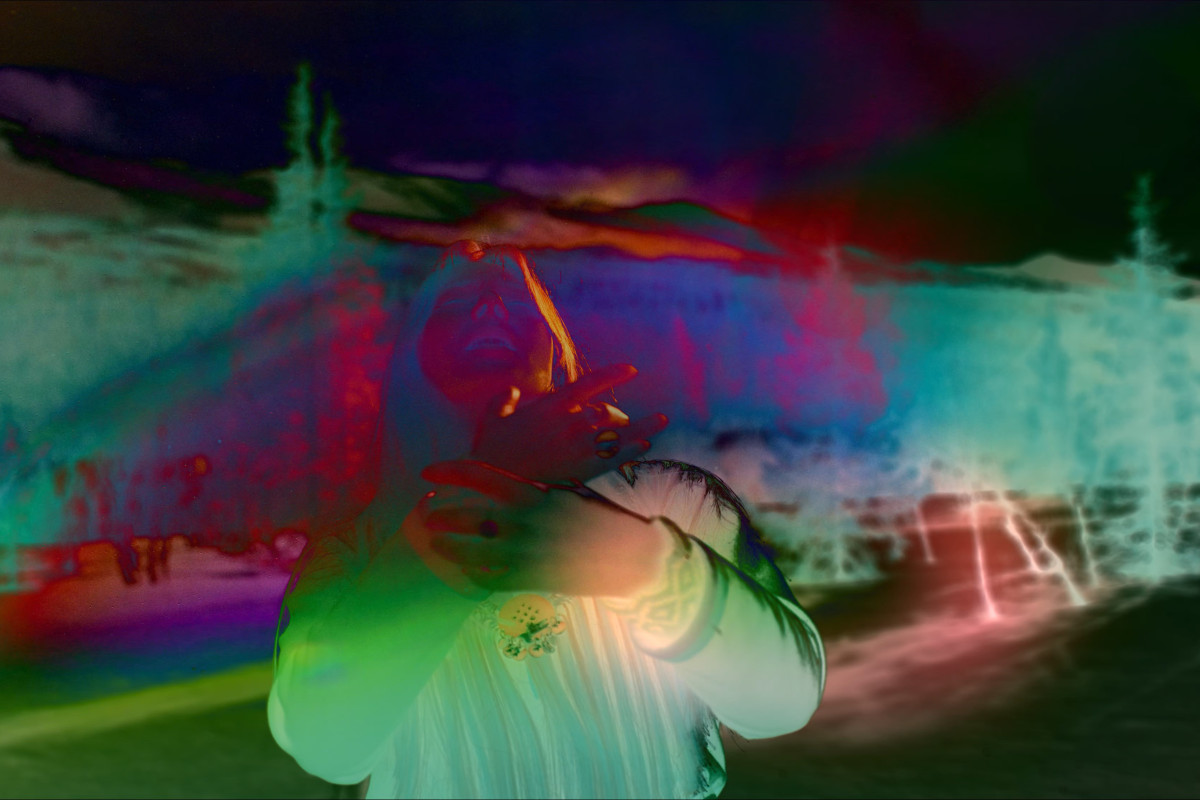

The editing shifts between a documentary strand of interviews and a surreal music-video aesthetic, where specially built cameras pan across the surface of the ice, bathing it in coloured filters referencing the northern lights and club lighting. In the interview track, the participants are allowed to steer the conversation themselves, which sends it in many directions. We touch on the spiritual undertones of traditional musical expressions, and here one would have liked the film to linger longer. One intriguing sequence explains how drum dance relates to the performer’s heartbeat, and how that rhythm is almost the same as the pulse of drill. More of that, please.

In a subsequent talk, the filmmakers explained that the work was originally produced as an audiovisual installation for five screens. That makes sense and might have worked better. Considered as a documentary film, Takkuuk is fragmentary, chaotic and directionless, which is a shame, because the young musicians seem to have much more to offer.

»Takkuuk«, Zak Norman & Charlie Miller (UK), 2025 (67 min). Screenings: 12, 17 and 19 March