Skulle have sendt min dobbeltgænger

Ideen fejlede ingenting: lige at komme ud og høre et par nye strygekvartetter. Det havde været så længe siden! Selveste Danish String Quartet med nyt fra næsten lige så selveste Bent Sørensen. Og et megaværk fra altid alt for uberømmede Niels Rønsholdt. Det burde ikke kunne gå galt.

Men hvad havde dog den fabelagtige Sørensen rodet sig ud i? Efter tre kvarters opvisning med Schuberts sprudlende, glødende, men trods alt ubønhørligt lange Kvartet i G-dur satte DSQ gang i Sørensens Doppelgänger. Som altså viste sig at være det sidste, man orkede i øjeblikket: en halv times remix af Schuberts værk! I nye klæder, natürlich, men forvandlingerne havde karakter af fikse idéer, der gjorde Sørensen mere menneskelig, end jeg huskede ham fra pragtværket Second Symphony.

Hvad der virkede elegant i symfonien – idéer, der cirklede spøgelsesagtigt rundt i orkestret – blev forsøgt genanvendt fra start i kvartetten. En simpel durakkord blev sendt på mikrotonal omgang mellem musikerne, så det til sidst mindede om forvrængninger i et spejlkabinet. Manøvren havde øvelsespræg, koketteri var indtrykket.

Derpå fulgte buer, der faldt ned på strengene som en hård opbremsning. Tyve minutter senere var figuren tilbage, men nu vendt om til accelerationer. Et forsøg på at fremvise sammenhæng i et værk, der ellers virkede unødigt rodet og sprang fra koncept til koncept? Lidt glidninger på strengene; dæmpning for at skabe en sprød cembaloklang; en lang, sfærisk passage; tilbagevenden til Schubert og tonika. Den gode Sørensen var blevet sin egen dobbeltgænger i processen, halsende efter forlægget. Jeg tillod mig et frederiksbergsk »åh!«.

Iført nye forventninger troppede jeg op til Rønsholdts 100-satsede Centalog to dage senere. Milde skaber, dette var endnu værre! Bag heltemodige Taïga Quartet tikkede et antikt vægur ufortrødent i samfulde 75 minutter. En fornemmelse af eksamenslæsning hang over os. Nøgternt præsenterede Rønsholdt selv de kommende satser hvert tiende minut: »10 left, 11 left, 12 left« eller »40 right, 41 right« og, koket, »13 left, missing item, 15 left«. Handlede det om læseretningen i noden, om strøgets bevægelse? Klart stod det aldrig, men tænk, om man blev hørt i lektien senere.

Fra Taïga lød febrilske fragmenter med aleatoriske linjer og abrupt dynamik; store følelser var spærret inde. Det forekom fortænkt, uvedkommende. Og med uvanlig distance mellem koncept og toner: Kun to gange undervejs spillede de kliniske opremsninger en smule med i musikken, da musikerne udbrød et bestemt »left!« her, et »right!« der. Hvor var Rønsholdts velkendte performative overskud? Mystisk. Fra væggen lød det blot: Tik-tak, tik-tak.

A World of Contrasts – and a Touch of Smurf Vocals

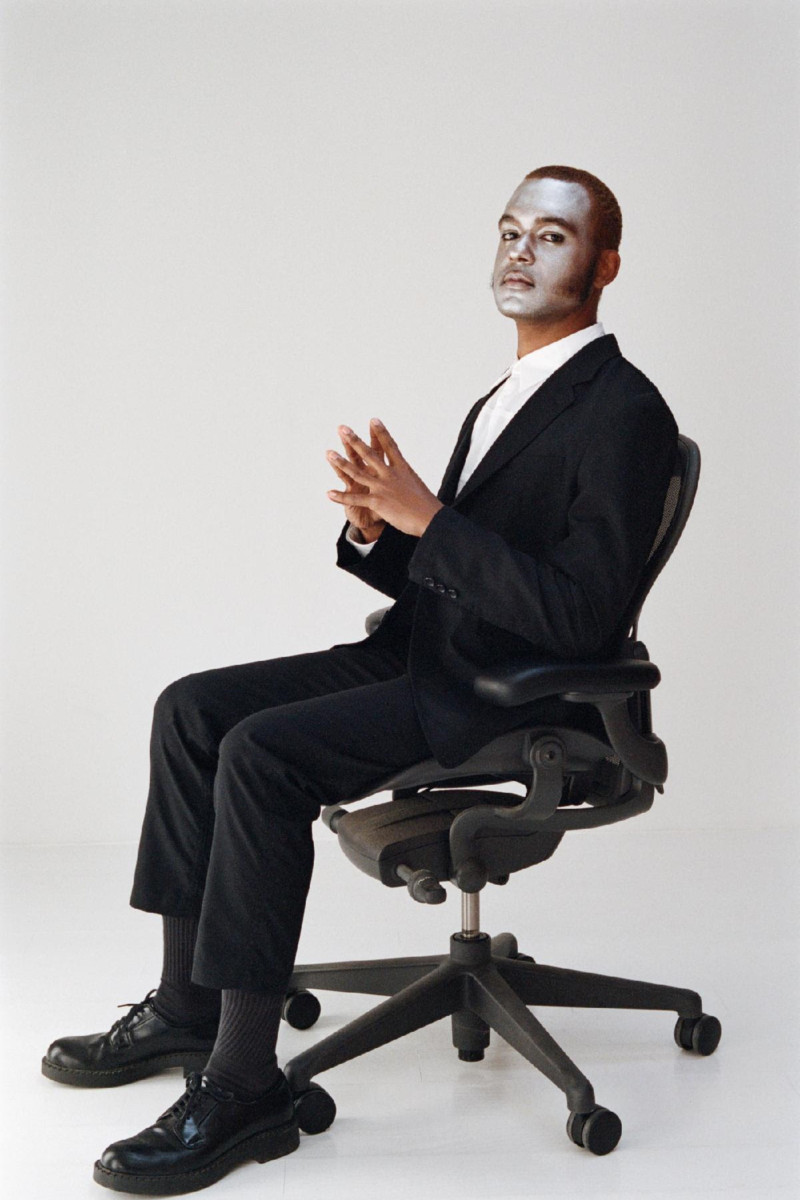

The cello is everywhere at this year’s Roskilde Festival. Some use it as just about anything else – hey, now it’s an electric bass, or how about a keyboard drowned in effects – but in American Jasper Marsalis’ Marcela Lucatelli-worthy bomb project Slauson Malone 1, the cello was actually used as, well, a cello.

Marsalis himself handled vocals and electric guitar on the open Platform stage, while Nicholas Wetherell opened the concert with a motor-race assault on his amplified cello, then pivoted into plucked meditations, to which Marsalis contributed overtone playing on guitar. Sensitive jazz guys? Nope – suddenly: synchronized noise sprints, intimacy splintered, and before long Marsalis threw himself into the seated audience with a somersault – and a scream.

Meanwhile, Wetherell played tender vibratos. Because contrasts thrive at Roskilde – and, after all, seem to be driving the world forward these days. And so it was the world itself that came into focus in the music: through violent shifts between 8-bit Smurf vocals, ambient gnawing solo cello, intimate indie layered over a one-second sample of Cher – culminating in a wistful lullaby veiled in digital theremin.

In many ways, it was peak hipster era. But it was also intensely moving – something like following Mahler out on the edge of the abyss as he tried to sketch the whole world into his scores. The only difference: the easel looks a bit different today.

Shouldn’t Selvhenter be playing the Orange Stage next year?”

It is not the first time Selvhenter have shown Roskilde how a saxophone can scream. Even the most avant-garde-ready listeners were left gasping for air. It was hard not to let your own lungs empathise with the long passages and unruly energy that the experimental Copenhagen quartet excelled in, wielding an instrumentarium consisting of two drum kits, synth, trombone, saxophone and assorted extras.

And the more the band – positioned in the centre of the Avalon tent, surrounded by the audience – wove their collective patchwork carpet, the more the individual character of the instruments was erased. Selvhenter could just as well have been playing entirely different instruments. You could see Sonja LaBianca standing there, forcing tones out of a wind instrument, yet it sounded more like a harp from outer space. It was astonishing how her saxophone fanfares resembled distress signals beamed into the cosmos. Meanwhile, the drums drove very grounded rhythms: Steve Reich-like pulses colliding with freer passages.

Selvhenter inflated the tent with full-fat punked and jazzy noise. Without pauses (not even when a snare drum went dead and had to be replaced mid-set) and without water for the crowd. Being so close to the musicians was a plus; on their small central stage they looked like giants in a battle arena. This was new music that was deeply physical. For about an hour we breathed together (and perhaps even sweated?) in sync. And it is profoundly good to do something together at a festival.

Selvhenter on the Orange Stage next year. Come on!

»Music involves a mix of noise, of existing or fabricated instruments, of alternative worlds that the sounds and voices assemble. Some are gentle, some less so. We shift gears with music, it shifts intensity, we shift with it. I listen when I can.«

Jussi Parikka is a Finnish cultural historian and writer who works at Aarhus University as professor of Digital Aesthetics and Culture. After some 15 years in the UK, he continues in Denmark his work on how ecology, digital culture, art and design, and philosophy intersect. He has written on visual culture and history and archaeology of media, including the recent books Operational Images (2023) and Living Surfaces: Images, Plants, and Environments of Media (2024) which is co-authored with the Madrid-based artist Abelardo Gil-Fournier. Besides his writing and work as educator, he has been active as a curator including the recent show Climate Engines at Laboral, in Gijon (Spain) that was co-curated with Daphne Dragona as well as his involvement in the curatorial team of Helsinki Biennial 2023.

What a Dial Tone Tells Us About Life

Crazy about phones? Then listen up. For British artist Beachers spent a day in his London office, and with his smartphone, recorded the sound of a landline waiting for you to dial a number after lifting the receiver. An innocent, yet somewhat insistent sound: Use me, beep-beep-beep-boop, now!

He cut up the recording, panned it around, shifted the pitch here and there, and dabbed it with delays. Turned it into musical material, in other words. And from the effort, Off the Hook grows small tones and harmonies like those from a self-built organ. But the office noises follow along, making the little album feel oddly haunted.

There are white creaks, maybe from a chair. Treble screams like distant, escaped parakeets. Short keystrokes, mysterious silences. After the harmonic organ opening, Beachers lets a deep bass rumble beneath chopped-up beeps. Layers are added, or sudden shifts occur. It’s not meant to be perfectly polished; you’re meant to feel that a human is playing with the digital.

Patiently, small pulses build, maybe even a beat. Listen to the hidden parties and drives of everyday life, the music seems to say—but also: see what we can do to pass the waiting time while forgetting what we’re actually waiting for—someone to pick up, the boss to let us off, death catching up to us.

In the end, only the raw recording is heard. A minute of beeps, boops, and random noise. As if each motif bows to its audience. What a strange release, nostalgically so in its way. And how creative.

Ballet’s New Power Duo

Josefine Opsahl herself sits on stage in the Australian-Danish choreographer Tara Schaufuss’s ballet Passengers of Passing Moments, for which Opsahl has composed the music. In fact, she almost steals all the attention from the ten dancers, as it is fascinating to watch the 32-year-old cellist’s theatrical immersion and her very active use of her right leg to control the loop and effects box.

The nearly half-hour ballet score is inspired by Bach, but also conveys a highland-like sense of drama through sampled breathing, stabbing subdivisions, and pronounced reverberation. It begins with delicate, bright major-key tones, but quickly moves into the depths, finding throbbing bass and timpani-like resonance. Emotions rush through every bow stroke.

The theme of the ballet is time. In fleeting moments, the dancers are caught in Opsahl’s small, mechanical loops; later, a dark, melancholic space is established, in which a young woman sinks into a memory. Extended sounds and overtones signal a time put out of joint; a faint wind is heard, a ticking fades in, and suddenly she has dreamed her beloved into being.

The woman moves like a ghost among the other bodies as Opsahl intensifies her playing, shifting between triple and quadruple meter. At one point, it is as if she disappears entirely into the violent temperament of the music; her dramatic flair turns Bach into an Avenger-like hero, and this suits Schaufuss’s focus on the force of emotions remarkably well. It is saturated, direct, and seemingly made for a grippingly intense choreography. A powerful partnership on the grand stage.