One of my most powerful art experiences of 2025 was British-Palestinian video artist Larissa Sansour’s intense work As If No Misfortune Had Occurred In The Night at Kunsthal Charlottenborg. The piece forms the basis of Thursday’s so-called »opera performance«, in which Palestinian soprano Nour Darwish performs in dialogue with Sansour’s visuals.

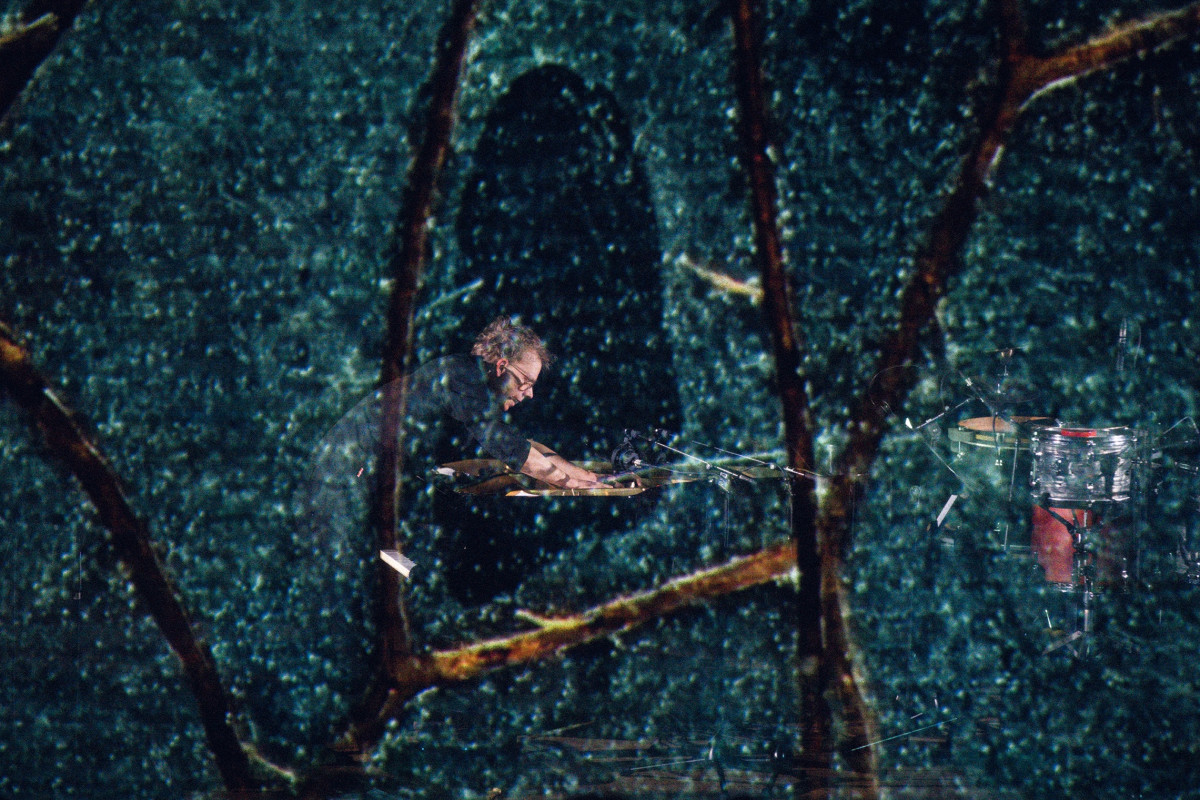

When Darwish steps onto the stage, it is before a vast screen where black-and-white scenes from an abandoned chapel establish a solemn atmosphere. It feels as though the entire hall is holding its breath as she begins to sing – tentatively, mournfully at first, then with spine-tingling force.

The composition draws on Kindertotenlieder (1905), in which Gustav Mahler sets to music Friedrich Rückert’s poems on the loss of two daughters. Composer Anthony Sahyoun allows Mahler’s music to merge with the Palestinian folk song »Al Ouf Mash’al«, a lament for a man who fell while serving in the Ottoman army during the First World War. Over time, the song has expanded into an oral account of Palestinian suffering. In its encounter with Mahler, it becomes a lament for centuries of grief – addressed to European ears that, through the colonisation of the region, bear part of the responsibility. Quite simply, it is a very good idea. At first, Darwish alternates between the two musical works, but gradually they fuse into a single narrative of sorrow, loss, and inherited trauma. She briefly leaves the stage, giving way to a filmed sequence in which she descends into a basin and is enveloped by indigo-blue water. In Palestinian tradition, indigo is the colour of mourning, because once it has stained skin and fabric, it cannot be washed away. It must be worn away – just as grief can leave us flayed.

Darwish returns in an indigo dress. At the climax, she falls to her knees as the screen behind her turns black, and I realise I have barely breathed for several minutes. The composition was created in 2022 – before the current war in Gaza – but on this evening, with her immense voice and intense presence, she adds yet another verse to the endless song. At times, art can feel brutally prophetic.

English translation: Andreo Michaelo Mielczarek