Doing it anyway

Schou is a powerhouse – unafraid to try new things, push himself in new directions, and pull us all along with him. We sorely need this energy, and we are lucky to have Schou and his do-it-anyway attitude.

But sometimes do-it-anyway needs tempering a little. Schou spoke about how he prepared this concert without guidance from his teachers. Brave, but I missed a guiding hand, a sharper focus. Both concerts were too long, and not always coherent. I sensed an artist who has defined himself by who he isn’t, but not yet by who he is.

Still, there were glimpses of a unique personality. Stefan Prins’ Generation Kill was an odd choice to start a debut concert with – Schou’s back was facing the audience, and the piece did little to highlight his skills as a performer (I also hated the piece, but that’s a personal matter). So I’m going to pretend that the concert started with Johannes Kreidler’s Guitar Piece – a vile little video-nasty to which Schou fully committed. A perfect manifesto – the absolute nerve of presenting two years of soloist class education by eating your guitar. I wish we’d had more of this playfulness.

But the energy sagged with a disparate selection of pieces that seemed more like a composer class concert than a presentation of a fresh artistic profile. Props to Schou for this – using your debut concert to focus on younger composers is bold, and should be celebrated. I just wish we’d had more Schou. My highlight was Emil Vijgen’s Photobooth Study, where Schou got to engage with his instrument in a different way, let loose a little, and be a soloist.

Schou may present himself as a force of nature, and he is, but there is an air of sensitivity (reticence, even) to his presence that does not always match up with the pieces being performed. Rob Durnin’s What, de facto could have benefitted from some more ‘fuck you’ attitude – the performance was oddly shy.

The late-night concert’s improvisation was fun: it’s always a joy to see Marcela Lucatelli and Henrik Olsson improvise (although Schou was the clear third wheel). However, the concert was overlong, and did not add much to Schou’s profile. I get that he wanted to show more sides of himself, but, again, it came at the expense of focus. Replacing Esben Nordborg Møller’s bloated Drones with Sarah Nemtsov’s lounge-jazz tinged Seven Colours from earlier would both shorten the concerts and sharpen the intention.

But these things are matters of polish. Schou is a rare and exceptional artist, and deserves accolades for his work and for these concerts. With more confidence and time to refine his vision, there is no doubt that Schou will be an essential fixture on the new music scene for years to come.

Vil hvalerne egentlig høre på os?

Den franske elektroniske musiker Rone synes, det er vanskeligt at udtrykke følelser verbalt. I Valentin Paolis ret rørende dokumentar The Musician and The Whale reflekterer han over musikkens evne til at skabe forbindelse og formidle stemninger til et publikum – uanset om dette er menneskeligt eller interartsligt.

En dag får Rone tilsendt en video fra en sejler, der afspiller hans musik på havet. Omkring båden flokkes hvaler, tilsyneladende tiltrukket af tonerne, og det bliver startskuddet for en undersøgelse af, hvorvidt musikeren kan kommunikere med dyrene gennem lyd. Rone opsøger en ekspert i hvallyde, der peger på bestemte high pitch synth-elementer i hans EDM-kompositioner, der kan minde om hvalsang. Han får et pigekor til at indsynge hvalens lyde med menneskestemmer og rejser derefter til det franske oversøiske territorium Reunion for at spille lydene tilbage til hvalerne.

I første omgang forgæves: Hvalerne synes ligeglade med pigekorets stemmer. Med et citat fra Goethe kommer Rone i tanker om, at hvis man skal røre andre, skal man tage udgangspunkt i det, der rører en selv. En Disney-agtig erkendelse i en lettere sentimental film, der taler til menneskets grundlæggende lyst til at kunne kommunikere med dyrene.

Men er vi egentlig sikre på, at dyrene gider tale med os? Rone gør sig, som filmens absolut bærende figur, enkelte dyreetiske overvejelser, men hans egen smittende begejstring for hvalernes lyde forhindrer ham i at stille de helt grundlæggende spørgsmål til forholdet mellem dyr og menneske. I stedet får vi et portræt af musikeren, der er nogenlunde lige så poleret og hjertevarmt, som hans musik. Hvalen, den holder sig klogeligt under havoverfladen.

»The Musician and The Whale« / »La Baleine et le Musicien«. Instr. Valentin Paoli (FR), 2026 (83 min.). Vises 11., 12. og 20. marts

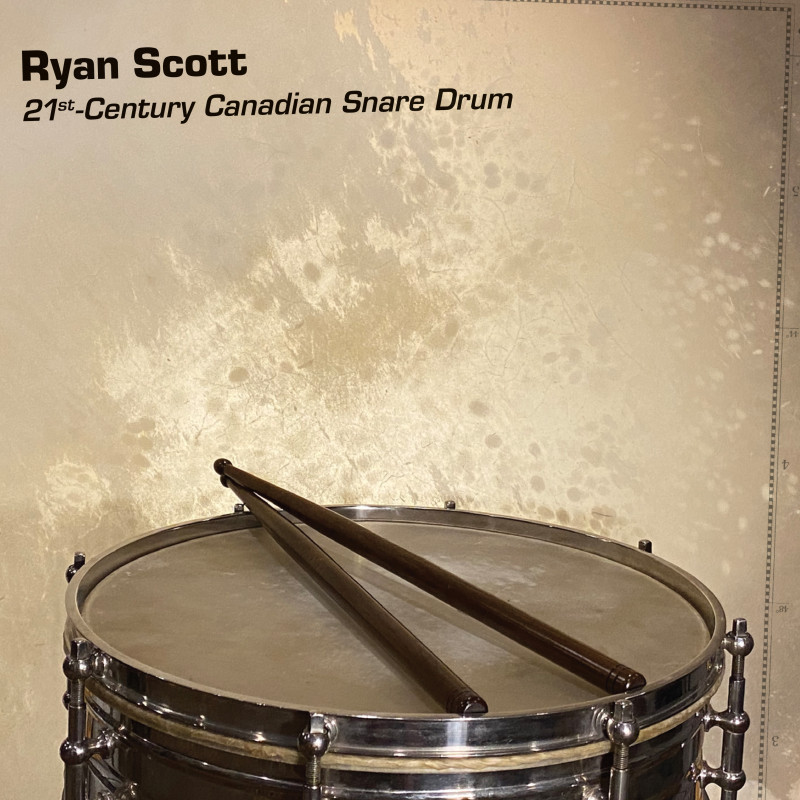

Alt hvad en lilletromme kan

Lad os være ærlige: Når man tænker kompositionsmusik for soloinstrumenter, tænker man ikke på lilletrommen. Den er måske det mest larmende medlem af slagtøjsfamilien og har i årtier sat lydniveauet i alt fra klassisk til pop. Derfor spidsede jeg ører, da den canadiske percussionist Ryan Scott annoncerede et helt album med værker for lilletromme – skrevet af 14 forskellige komponister. Endda halvanden times musik. Og jo, det lyder som meget for en plade, der primært består af én tromme. Men der er bestemt noget at komme efter.

Andrew Stanilands åbner, »ANTIGRAVITYDRUM«, der blander freejazz med inspireret brug af percussiv vibrafon, mens Beka Shapps’ »Skinscape IV« sender trommeslagene gennem ringmodulation og omfattende lydbehandling, så vi er tæt på musique concrète. Christina Volpinis »only ghost« sniger sig ind i horror-territorium med marchtrommeinspirerede stød og spøgelsesagtig brug af lilletrommens diskant, mens Amy Brandons »Time and Effort« næsten bliver en demonstration af instrumentets tekniske muligheder.

14 værker over halvanden time er en stor mundfuld. Lilletrommens begrænsede tonale vokabular gør, at man indimellem falder af, selv efter flere gennemlytninger, og kontrasten mellem trommeslag og stilhed gentages lidt for ofte. Når det er sagt, får Ryan Scott og komponisterne omtrent så meget ud af en glorificeret gardertromme, som man kan. Jeg var både underholdt og tankevækket undervejs. Som eksperiment er idéen stærk – men i længden også så insisterende, at jeg næppe vender tilbage. Alligevel: Man skal ikke undervurdere alsidigheden i en god gammeldags lilletromme.

»Musik for os er en måde at skabe en forbindelse og et fællesskab til andre mennesker.«

Selvom Schæfer indtil videre kun har udgivet tre singler, har bandet allerede markeret sig på den danske musikscene. Duoen og venneparret, Anna Skov (vokal) og Emil Mors (keyboards), skriver samfundsaktuelle, underfundige og humoristiske sange, der peger fingre af både omverdenen og dem selv.

»Musik for mig er en åben vej til eventyr, hvor alt kan ske. Musik for mig er en frihed, der rummer alle følelser. Musik for mig er det allermest private og noget, som mange kan dele. Musik for mig er uforståelig, oplysende, underholdende, religiøs, filosofisk, vibrerende, magisk og den stærkeste kraft, jeg kender. Musik for mig er noget, der gør mig opmærksom på livet. Musik for mig er en fri fugl.«

Gustaf Ljunggren er en svensk musiker og komponist, bosat i København. Hans værker bæres ofte af en vilje til indadvendthed og fordybelse i en støjende verden. I 2026 udgiver Gustaf Ljunggren albummet Along The Low Road, skabt i samarbejde med den islandske musiker Skúli Sverrisson. Ljunggren medvirker på hundredevis af udgivelser som instrumentalist og arrangør, og han har gennem årene samarbejdet tæt med Emil de Waal, CV Jørgensen, Steffen Brandt, Sofia Karlsson, DR Pigekoret, Eddi Reader, Anders Matthesen og mange flere. For den brede danske befolkning blev Gustaf et velkendt ansigt, da han var kapelmester i Det nye talkshow på DR1 med Anders Lund Madsen som vært. Siden 2011 er Gustaf Ljunggren tovholder for SPOT Festivals koncertserie Naked.