Mediating Music - Music, Publishing, Art and Memory in the Age of the Internet

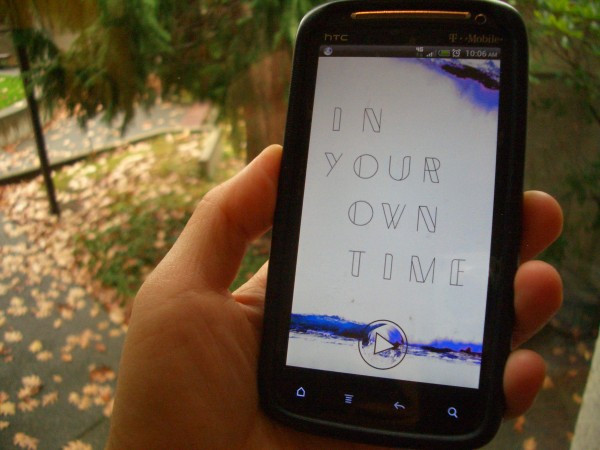

It is late 2013. I Care if you Listen, a New York based blog about “new classical music, art and technology” that also has a magazine on the Apple iOS Newsstand, reviews In Your Own Time – an “adaptive musical composition designed exclusively for performance on mobile devices. Audiences experience the piece through the app, which uses feedback from the listener’s surroundings to alter the playback of the music, making each ‘performance’ of the piece unique.”

There is an impetus to understand these technological developments. On the other side of the Atlantic a collaborative project between three Nordic publications on sound art and contemporary music includes the following in a project description:

Technology has been an all-important and defining element within the arts throughout the 20th century, and it has fundamentally changed the ways in which we produce and consume artefacts, especially within the field of sound art and music. The challenge to understand these changes has not diminished in the new century – on the contrary, the need for a closer connection between the arts and their reception seems to be even more pressing in an age where technological innovations and digital opportunities change both the arts and the consumers’ habits of consumption at a rapid pace. (The Idea of North, project description)

Although music and technology have a well established relationship, I nevertheless find myself asking why so few composers have embraced the web as a possible space for unfolding their music other than putting up what amounts to a kind of brochure with a list of the works they have composed. 1

In order to better understand where we have gotten to in a world of personal devices, apps and the internet, I propose a brief step back in time: A look at what the technological developments of the past few years have meant for both communities and individuals and how we might create a map for both navigating the possibilities open to us and harnessing their potential in the future.

Part One

A brief history of life since the iPhone

In 2007 Apple introduced the iPhone and a revolution was set in motion. For the first time a fully fledged web browser was available on a mobile device. In the same year Amazon introduced their Kindle and reading on digital devices took off. Three years later the iPad was introduced and extended the Kindle's eBook realm to include the web. Within a short space of time our relationship to the internet had changed drastically. Interaction with these new devices was through touch and gesture and the growing availability of solid WiFi and 3G networks meant that we could access the web wherever and whenever we wanted. Not only did we abandon the public libraries or internet cafe terminals that were once used to access our hotmail accounts, we were also suddenly liberated from the confines of our desks. Even more so than with laptops, these were devices that we had close to our bodies throughout the day. Computers had changed from huge communal devices in remote rooms to personal extensions of the body. 2

Content First Responsive Web Design

For those creating the content and designing the websites that we now had constant access to, the challenge was to find ways in which to make that content more ‘mobile friendly’. Designers began to look back to the more fluid origins of the web, to a time before attempts were made to get web pages to behave more like print media. In 2011 Ethan Marcotte joined the dots and Responsive Web Design (RWD) was born. Rather than create separate sites for mobile and desktop use, a single design would fluidly and intelligently adapt to the devices it was viewed on. This had a huge impact on aspects such as readability. Just because you were reading a text on your smartphone didn't mean that you had to squint your eyes to do so or zoom in to the text you were interested in. The smaller screen sizes and lack of bandwidth also prompted a re-evaluation of how content itself was approached. There was no longer place for the distracting banner ads, complicated navigation or heavy media files characteristic of desktop sites. A new “content first” movement was afoot. And as fortune would have it the availability of a wide range of fonts available for use on the web via services such as Typekit (introduced in 2009) in conjunction with high resolution “Retina” displays (in 2010) convinced designers that a well presented text could be enough. As with gastronomy a few simple ingredients of high quality, intelligently combined, were all that was needed for a sublime experience.

From Subcompact to Snow Fall

These developments had, of course, a huge impact on the publishing industry. Gone were the clear cut boundaries and controlled layouts of the print era. The RWD revolution was based on flexibility but publishers were reluctant to give up the control they were used to – both aesthetically and conceptually. On the one hand it was assumed that technological advances would bring the digital realm closer to that of print and on the other that they would open up the way for the increased inclusion of media and “interactive features”. Traditional publications had a hard time living up to the promise of these new developments and floundered both technically, conceptually and financially in their attempts to create digital versions of their publications.

In October 2012 Marco Arment cut through the chaos with the introduction of The Magazine – a publication that built on his experiences with Instapaper, a “read later” service that stripped web pages of all that was extraneous in order to serve and store the core content. The Magazine kept things clean and simple and delivered a quality reading experience on the basis of a subscription model. Craig Mod summed up the characteristics of this approach in his article “Subcompact Publishing” and the impact of this disruption quickly rippled throughout the internet. This was a model well suited to a challenged global economy – imitators followed and soon even niche areas such as ‘New Music’ had the means to produce their own viable publications.

Craig Mod – “The Magazine” Screenshots, source: http://craigmod.com/journal/subcompact_publishing/

Craig Mod – “The Magazine” Screenshots, source: http://craigmod.com/journal/subcompact_publishing/

On the other end of the spectrum larger players such as the New York Times and The Guardian had the resources to invest in cutting edge showcase projects such as Snow Fall and the NSA Files. These are in-depth articles that make use of available technologies in a very sophisticated and intelligent way. Back at the other end of the scale it hasn't taken long for “subcompact” publications such as The Loop to start getting a little more fancy either – the lure of possibilities is apparently always around the corner when it comes to digital technology.

The Independent Web.

While Subcompact and Snow Fall might establish the extreme poles from a (new) journalistic point of view, there are also what Jeffrey Zeldman refers to as the independent content creators – those sharing ideas and passions on “the only free medium the world has known” either in the form of blogs or on their own websites.

Blogging has existed for some fifteen years and technologies have placed it within easy reach of all. Some have felt the time ripe for a reconsideration of it's form. How might a better, less chronologically based, cross pollination and exchange between all the individual content creators take place? It is exactly such questions that a platform such as Medium is attempting to answer – aiming for a spot in-between large scale journalism and the independent bloggers. The strategy is to make it as convenient as possible for individuals to share their ideas on a platform fine tuned for a quality reading and writing experience – the quality of the form hopefully establishing an environment for equally inspired content.

One might however argue that this attempt to entice bloggers out of their individual bubbles results in the creation of yet another content silo. Many have burnt their fingers with finding their content locked in to large companies or simply lost. And as with nearly every free service the price that users are paying is the use of their data in unsavoury and suspicious ways – if not by the companies themselves then by the governments imposing themselves on those companies. Medium is fortunately generous with its terms of use. Copyright is non exclusive and users have the possibility of exporting their content should they wish to. Nevertheless the business model remains unclear and one is to some extent beholden to the whims of the platform one makes free use of.

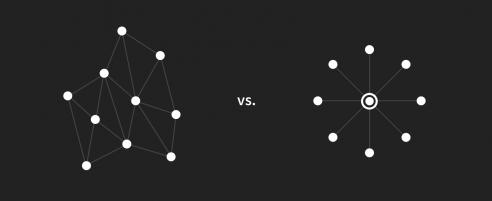

All of which has given extra impetus to the indie web movement, which has as one of its core principles that web creators should own their content and data by being their own ‘platforms’ – by posting to their own blogs or websites and syndicating out to third parties should the need arise. In this way individuals could take back some degree of control while maintaining an open web – a return to the principles the web was founded on. A web made up of a wide distribution of small pockets – whether individuals or small communities – each with the possibility of connecting and sharing with one another directly, rather than relying heavily on centralised services leading to a web in which too much power resides in the hands of a few companies.

Blurred Lines – a (not so) seamless experience

The compartmentalisation imposed by those large companies was however to some extent at odds with the way people were using the internet. Although web designers were at first forced back to the basics, the rapid development of both hard and software soon meant that within a short space of time the “mobile web” was no longer a second rate version of what could be accessed through desk/laptops. The web was just the web and even though desktops now might be more associated with work and tablets with recreation, one could no longer make assumptions about those modes of use. People began tasks on one device and completed them on another. Boundaries were increasingly blurred.

RWD principles invloved building a single site that would respond to the way in which it was accessed rather than dividing sites (and the web) into “mobile” and however many other versions. Such divisions inevitably created hiccups for the users constantly traversing these “boundaries”. Over and above RWD, the development of syncing technologies such as Dropbox and iCloud also played a crucial role in establishing (hopefully) seamless transitions from the one device/situation to the next. We needed to access not only websites but also the documents or media we were working on or wanted to share. Software, services and hardware were no longer separate domains – they were now indispensable (complementary) ingredients of modern (digital) life.

Platforms and Apps – Tools and Content

That life remains, of course, far from seamless. The biggest transitions continue to occur when crossing the border from one closed proprietary platform, from one big company, to another. These transitions are especially apparent when considering the differences between apps and websites and underline the philosophical differences between the two approaches: If I, as an (sound) artist, choose to make an ‘app’, I take on the both the strengths and confines of the chosen platform. As with publishing platforms one is bound to the rules and whims of those in control.3

Whereas RWD aims for one (open) thing taking on many forms, apps tend toward division. For individual creators and the cultures they both contribute to and draw on, choices might tip one way or the other. We choose the tools best suited to our (creative) needs, to some extent defining ourselves by those choices (and the platforms that come with them). While that definition might be valuable to us as individuals, we might also question where we would like to draw the lines (if any) when it comes to our artistic and cultural contributions.

When it comes to artworks the long-term viability of the platform one chooses can have implications that are easier to ignore when making tools tied to the limited time spans of operating system development cycles. Should one wish to reach past the visual styles and features of the software currently running on our devices the web is clearly the medium with the best long-term prospects.

Apps nevertheless offer certain enticing possibilities when it comes to art: On mobile devices they fill the screen and place the user in the world of the app. The browser bar disappears and with it the temptation to run off to another corner of the web. When it comes to works of art on the net this might easily be seen as something to be embraced – such “immersive” features provide a welcome counterpart to the noise of the web and potentially help create a space for the experience of the work itself. However, in touching on the aspect of user experience we also find ourselves on a slippery slope on which art seems to be sliding towards design.

Immense amounts of time, money and ingenuity are invested in the development of software tools which are iterated (and thus developed) at a scale and rate that can only be dreamt of in the arts. This is where some of the best minds of our generation are applying their energies. The need for cohesive design principles that favour usability is however potentially at odds with drives towards (individual) artistic expression – so much so that questions are being raised as to a possible parting of ways between the two disciplines.

Paul Soulellis – counterpractice, source: http://counterpractice.tumblr.com

Paul Soulellis – counterpractice, source: http://counterpractice.tumblr.com

The world of apps and the web, and the increasingly blurred lines between them, present artists with a difficult set of options to navigate and no easy answers at hand.

Part Two – Specifics

There is more to the web than sharing

But what roles is the web fulfilling for us, over and above the obvious aspects of access to information, tools, communication, sharing & collaboration? Our use of smart devices is so close to the body that it has entered our psychology and radically modified our behaviour in ways we are only beginning to realise. We have to some extent already become the cyborgs of our once future fantasies.

There is however apparently more to the web than sharing. It has also become a place for us to mirror our thoughts and store our memories – for ourselves. A place to externalise that which we are carrying around internally. Digital journals, ‘to do’ lists and bookmarks help us get the overwhelming amount of information we are dealing with organised and out of our heads.

Hi, a recently launched website, epitomises some aspects of this. It builds on the idea that memory is closely connected to a sense of place and offers users the possibility of uploading pictures or a snippet of text from their smartphones (or whatever device) when inspiration strikes while out in the world. These “moments” can later be expanded upon and published as short stories or journalism. Or kept private. The internet has become a place for us to mirror our internal lives. Not so much a duplication of the world but rather a record of our experience of it, of our perception of it. A personal map that can be returned to, filled out and possibly shared.

When seen from this angle it is no wonder that many have been so infuriated by the recent scandals concerning government surveillance. It is as if our inner lives have been trespassed upon. One of the most defining features of our personalities – the choice of what we make known to others, of what it is we choose to share, has been taken from us. Of course we take it personally. The internet has become inextricably entwined with the mental map we have of ourselves.

The Art of Memory

Web designer Chloe Weil builds some memory maps and demonstrates the potential value of owning your own data with Sound of Summer – a simple web thing that mines a decade’s worth of stats collected in her iTunes library to take a charming trip down memory lane.4 Chloe is a good example of someone fully embracing indie web principles, even going so far as to publish tweets directly from her own site. She has the ‘original’ tweets on her server which are then (also) shared with the world via Twitter’s service:

Personally, I felt liberated by the broader idea that services like Twitter, Facebook and whatever comes along in the future would be representations of me, rather than “me, elsewhere.”

While this may seem somewhat extreme it indicates the need many are feeling to collect and regain control of their digital selves after years of spreading their identities across diverse services.

She also unfolds some aspects of her family history in a wonderful web essay Julius: The Cards. This is the indie web at its best and a worthy counterpart to institutionalised journalism. In a blog post about its creation she outlines her concerns about designing for the web with digital preservation and future friendliness in mind. A project that extends from the directly personal to include aspects of collective memory.

In his wonderful essay The medium is the mold Matt Steel attempts to come to grips with the questions, first raised by Marshal McLuhan, concerning the way in which our forms of communication shape us, both individually and collectively. Steel distinguishes between oral and literal cultures and the means they use to store and retrieve information: literal cultures learning via an abstract, explanatory examination of information and oral cultures sharing knowledge verbally:

The sheer volume of information they had to memorize – and could retrieve verbatim on demand – are overwhelming to the modern literary mind. However, oralities are not without systems and supports that allow them to store and retrieve information. Their feats of memory seem more attainable when we consider their reliance on verbal rhythms, formulas, repetition and even cliché.

That sounds to me like something closely tied to music – perhaps not so much music as personal expression, but as pattern forming aid to an art of (collective) memory.

The web might in fact be closing the circle in certain ways and offering a new hybrid between these literal and oral forms. It is in many ways the perfect container for archives of oral history. Jeremy Keith's The Session is, for example, a collection of Irish folk music inspired by O’Neill’s One Thousand and One Melodies – O’Neill being an Irish policeman living in Chicago in the middle of the 19th Century who saved much Irish music from extinction in the Irish diaspora by establishing a vast collection of the tunes he notated. The Session is a modern day web version of such a collection largely built up by contributions from enthusiasts. A living collection existing someplace between an oral and literal culture.

Music as an Art and the Art of the Web ?

Where does this leave me as an individual content creator (primarily interested in sound)? Why is it that so few composers have embraced the web as a possible space for unfolding their music other than posting a list of their compositions, perhaps also with the addition of some YouTube videos? Has the web been equated with the companies that dominate it – with Facebook and Twitter? Is it that in light of all the mess of sleazy business practices, surveillance and misuse of our data that we wish to keep music in a purer, more real, place – somewhere away from the web? A place in which we still have the possibility of feeling the vibrations in our feet and meeting each other face to face for a beer after the concert? A refuge from the all pervasive digital aspects of our lives?

Is it that the technical threshold for taking the indie web route remains set too high? (The big platforms have made it convenient for everyone to put their stuff out there but the indie web still requires some degree of tech savvy.) And if so, why is it that many composers have no trouble diving into the complexities of creating Max patches but draw back from the relative simplicity of HTML? Would those technical hurdles be tackled if there was a greater impetus to do so? 5

Is it that the nature of coding is at odds with the freehand expression that comes with using a pencil or playing an acoustic instrument? And if so, then what of the growing live coding community.

Or is it the conceptual models for dealing with music on the web that are lacking? Is the web at its core simply too centred around texts and images? How do we go about creating a context for musical compositions on the web?

Creating a context

Having one’s own website (and not just making use of hotels such as SoundCloud, fine as they may be) might be seen as the single most important ingredient in creating a context for one’s works – the first step in establishing a home on the web.6 The next being the development of conceptual models to expand on that basic context. As Frank Chimero points out in his wonderful web essay "What Screens Want", the abstractions we have accepted when it comes to computers and the internet can both help and hurt us. We constantly make use of metaphors from both other media and the physical world in order to navigate the digital realm. It is worth our while to investigate those abstractions.

One might argue that the sparks that arise when one medium comes into contact with another shed light on both. The challenge of the digital realms presents an opportunity for those practicing the art of composition to reconsider inherited assumptions.7

Where are the composer counterparts of Frank Chimero’s web essays? The explorations of how Attention, rhythm & weight might be played out in sound?

Most museums (of modern art) invest a good deal of energy in putting together the texts that surround the works of art they put on display. Quotes, anecdotes and historical/philosophical background fill in context and shape how we perceive the work itself. In the case of sound-files on the web we are often presented with a number of works thrown together in a noisy room with little in the way of clues as to the intended context(s). We are left to our own devices.

As the conceptualists of the last century discovered, those bits of (con)text might be an important aspect of the artworks in question – so much so that they might become artworks in their own right.

The great work of sites such as I Care if You Listen, NewMusicBox and individuals such as Seth Kim-Cohen aside, why is it that there are so few blogs on new music and sound art? Johannes Kreidler is an exception that immediately springs to mind – an example of someone using the blog format in a way more interesting than the somewhat traditional style of the American publications mentioned above. In Kreidler's case, his blog is indeed an artistic outlet that very much suits his neo-conceptual approach. His "Ear Training" series is a delightful example. Or Sebastian Claren's pithy entries to his Material on Wordpress.

Johannes Kreidler – Ear Training, source: http://www.kulturtechno.de/?p=11069

Johannes Kreidler – Ear Training, source: http://www.kulturtechno.de/?p=11069

Perhaps these are the beginnings of not just sharing music via the web but creating a true art of the web. Artistic voices in a designed world.

Epilogue

Late 2013, North of Copenhagen: On entering the Louisiana Museum’s Arctic exhibition one is presented with the following quote:

Two ideas of North: North is both the place of darkness and death, the seat of evil. And the place of austere felicity where virtuous peoples live behind the north wind and are happy —Peter Davidson

A century ago it was the arctic expanse that both inspired and terrified. Today the quote above might equally apply to the territory that has captured the modern imagination – the internet.

- 1. Popular musicians such as Johnathan Mann have, for example, embraced YouTube as a medium, creating for the web rather than simply using it as a channel for news or distribution.

- 2. Or rather, we have come full circle and now have both ends of the spectrum – small highly personal devices on the one hand and “abstract” locked away server farms owned by huge corporations on the other

- 3. For publications such as The Magazine that commit themselves and even have their point of departure in the features of a single platform, the existence of a corresponding home on the web is essential.

- 4. Designer Khoi Vinh suggests something similar for services like Spotify: https://medium.com/what-im-reading-on-medium/9a56e22682d4

- 5. When compared to creating 'native' apps the web is at present a great deal more accessible – for both creator (the technical hurdles involved) and audience.

- 6. This, of course, very much places the seat of artistic practice in the realm of the individual. One could however imagine a more neutral ‘place’ – a ‘site’ that still adheres to the same (indie) principles while avoiding the cosiness of the ‘home’ metaphor.

- 7. Where is the investigation into how seeing where one is in the overall duration of a media file affects how we perceive and use it? The investigation into how forms of navigation such as scrolling and swiping affect how we relate to sound? How might we realate to music when it is (once again) no longer so tightly bound to objects or pages.