A sonic time capsule

In 2012, to finalise my one-year diploma course in sound and music technology at the London College of Communication (LCC), I wrote A Sonic Time Capsule – a small instruction manual explaining how to realize such a thing. It felt slightly wrong to be writing about sound for my final project rather than creating a sound piece; but I was after all studying at the former London College of Printing. I was interested in creating a text-based structure which would have the potential to produce and preserve sound, rather than a sound piece that would irremediably fix an assembly of sounds into a recording. Writing instructions for a sound piece rather than executing them maintained the open-ended potential of sound I was interested in exploring.

The design of this manual was inspired by the ‘Printing Historical Collection’, from London College of Communication’s special collections. Its chronological sampling of private press, artists’ books and fanzines is an attempt to chart the history and art of the Western book, reflecting its physical, technical and aesthetic development from the 15th to 21st centuries.

Andrea Zarza Canova in The British Library Sound Archive.

Andrea Zarza Canova in The British Library Sound Archive.

At that time, it had been a few months since I had started working at the World and Traditional Music section of the British Library Sound Archive. Immersed in that environment, I was thinking about the permanence of sound, and how sound carries information about the time period it was produced in. During my work placement, one of the main projects I did was catalogue Charlie Gillett’s World of Difference and City Beats radio programmes, which had been aired on Capitol Radio London between 1986 and 1989. These programmes were crucial for building a scene around world music in London, and included unique interviews with DJs, journalists, musicians and record label owners. The texture of the late 80’s was palpable in the programmes – though at times, the music felt utterly contemporary. For example, one of the most striking albums I discovered through Charlie Gillett, though not directly aired on any programme, was Hector Zazou, Bony Bikaye and CY1’s collaboration on Noir et Blanc from 1983, and it has recently been reissued by Crammed Discs.

Lastly, I remember overhearing something one day that inspired me. I was in the computer lab at LCC mixing a piece on ProTools and next to me were two students sharing the fruits of their labour, something on headphones which I could vaguely make out to be a rhythm-based track. After one of them listened to it, he loudly and passionately exclaimed to his friend – »this sounds like now«. This was the most immediate and adequate complement that had come to his mind it seemed. It made me wonder what now would sound like if we were explicitly asked to compose it.

More than five years later, A Sonic Time Capsule will be part of a workshop in Copenhagen, Denmark, thanks to an invitation from Jan Høgh Stricker and Rasmus Cleve Christensen from Seismograf and The Lake Radio. I have previously presented the instruction manual at the British Forum for Ethnomusicology’s Conference that took place at the Pitt River’s Museum in 2012, at the London College of Communication, and it has been translated into Spanish for the fanzine Ursonate, as well as into Basque by Audio-lab. However, the instruction manual has never been used for a workshop, and I am excited to see what it will sound like!

A SONIC TIME CAPSULE

»A sound, a whole sound is not separation, a whole sound is in an order.« (Gertrude Stein)

INTRODUCTION

This document attempts to lay out a path towards the creation of a sonic time capsule. It can be read like a map, a score, or an instruction manual. It is a prototype for action, and hopefully, through time, it will grow and multiply with the experiences of others. Right now, it is nothing other than potential; its consequences are yet to be determined.

What we have in mind is to make possible a gathering of those who are interested in listening to the present. Although sound is our privileged medium, we welcome thinkers from all disciplines and backgrounds. In fact this inter-disciplinary approach is crucial to the workshop since sound is something we are all involved in, something that concerns us all. The only requisite for participation is a willingness to listen and go beyond our aural comfort zone.

By listening to the present we mean engaging with it critically: problematizing it, questioning it, bringing forward our concerns, hopes, preoccupations and desires about that which we all have in common; we want to open up »a strong oppositional place of conscious listening« (Westerkamp, 2002).

The time capsule helps us travel the necessary distance to make this type of listening possible because we are aware that it is difficult to detach oneself from the present.

The reason for the difficulty of contemplating and talking about sounds heard around us may be that the world of sounds is too close, too 'present'. As one of social science's challenges is the self-evident, talking about the 'absent' and the 'ideal' may create a comfortable distance to the subject studied. As well as sound memories turning towards the past, acoustic Utopias referring to the future, offer temporal distance. (Vikman, 2002, p. 162)

Even though the activity is about creating a sonic time capsule, we are more interested in what can happen in the process of the making than in the result. However, we would love to perform the contents of the time capsule before burying it. What may be sealed away is what we'll have to decide together.

1. WHAT IS A TIME CAPSULE?

The term 'time capsule' loosely refers to a discrete body of evidence, either of the past preserved against interference until the present, or of the present similarly preserved for posterity. A narrower definition adds the idea of intention: a time capsule is the result of deliberately setting aside what a hypothetical future finder is anticipated to regard as evidence of the present (Durrans, 1992, p. 51)

Time capsules are one way people have of leaving an explicit record of their existence. The disparate elements that can be found in a time capsule all have one thing in common: they express the encapsulator 's experience and understanding of the present. Time capsules can be vessels containing extremely personal items, a sealing away for the future of the meaningful and significant moments (inevitably materialized) that sum up one's life.

Imagine compiling the contents of your very own time capsule. You are choosing the parts of a story you will no longer be there to tell, so only the physical traces will speak to a distant and hypothetical other who will recount what you once were. What would you include?

The action of compiling and depositing a time capsule therefore implies not only reflection on the nature of history (the archaizing effect of time capsules as a category) but also the creative provision of historical 'evidence' (the appeal of each capsule as a unique message). (Durrans, 1992, p. 53)

This type of time capsule, of a very private and intimate nature, speaks mainly of its author, however »That every individual life between birth and death can eventually be told as a story with beginning and end is the prepolitical and prehistorical condition of history, the great story without beginning and end.« (Arendt, 1958, p. 184) It might be found in between walls, buried in backyards, in attics.

The Crypt of Civilization

Macrocosmic time capsules (Durrans, 1992) attempt to describe a civilization. The Crypt of Civilization at Oglethorpe University (Atlanta, Georgia, United States of America) is one of the largest time capsules of this sort in the world. It was sealed off on May 28th, 1940, with instructions to not be opened until May 28th, 8113 A.D. (Dr. Thornwell Jacobs, creator of the crypt, calculated the number of years that had passed between the first fixed date in history, 4241 B.C., and the year in which the crypt was conceived, 1936. He arrived at a figure of 6177 years, number which he then added on to the date the crypt was sealed in order to determine the opening date). At the sealing of the crypt, which was broadcast by Atlanta's WSB radio, Dr. Thornwell Jacobs made the following statement, addressed to the future openers of the crypt: »The world is engaged in burying our civilization forever, and here in this crypt we leave it to you.« (Hudson). The endless inventory of items in the crypt attempts not only to be a repository of 1930's culture but also of civilizations' greatest feats.

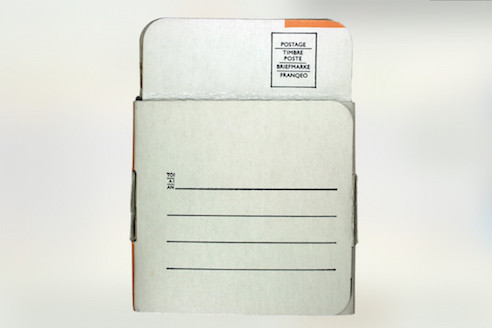

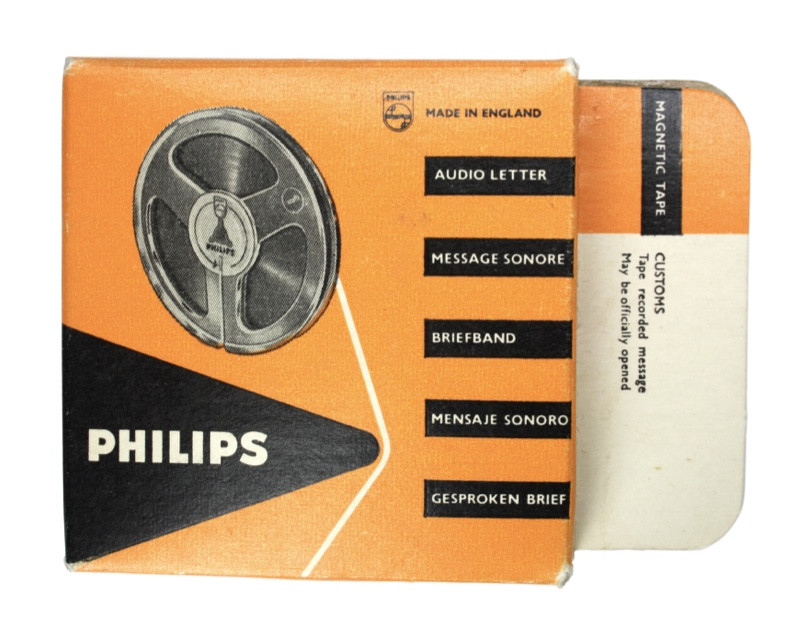

Examples of some of the things that can be found in the crypt are: microfilms of the Bible, the Koran, the Iliad, voice recordings of public figures such as Mussolini, Hitler, Roosevelt, Popeye the Sailor, an original copy of the script of 'Gone with the Wind', 1 set of Lincoln logs (toys), 10 samples of textile upholstery, 1 model air conditioner apparatus, a male and female manikin each in their own glass case, etc. Upon entering the crypt, the first item one will find is a manual explaining how to learn the English language. In the crypt one will also have access to all the machines needed (reel-to-reel tape machines, microreaders and projectors) to reproduce the items stored on specific formats. In the case of a lack of electricity, the crypt is equipped with a generator operated by a windmill.

A gesture such as the Crypt of Civilization's one, of aspiring to capture a snapshot of civilization, is most likely powered by an anxiety with the permanence of the present and a need to lay out a place for it to remain (in this case one measuring 20 feet in length, 10 feet in height, and 10 feet in width). This way of assuring future space for what we deem significant reveals a hidden desire of many time capsules: a will to influence the future.

However, we must realize that a time capsule promises longevity to ephemeral things but not to their meaning (what kind of a preservation technology would be able to guarantee this?). There is no way to ensure that the relationship between signifier and signified remain intact no matter how well the crypt may be sealed.

Alvin Lucier's North American Time Capsule

Discovering Alvin Lucier's North American Time Capsule (1967) was a definite source of inspiration for this project. We had been trying to create instructions for a sonic time capsule for some time before stumbling upon it. This was always the hardest part for us as we continuously got stuck on how to phrase what it was we wanted performers to sound. Not that we were hoping to describe that which should be encapsulated, and then have others sound it.

Alvin Lucier's score provides a clear cue on how to make a sonic time capsule:

Prepare a plan of activity using speech, singing, musical instruments, or any other sound producing means that might describe - to beings very far from the earth's environment either in space or in time - the physical, social, spiritual or any other situation in which we find ourselves at the present time. Using sound, the performers might choose to convey, for example, the ideas of life and death, young and old, up and down, male and female. Sonic aspects of our technological environment, such as household appliances, trains, aircraft and automobile horns might be used. (Lucier quoted in Ashley, 2002)

Following this score, students from Brandeis University, where Alvin Lucier was director of the Chamber Chorus, performed the sounds. Alvin Lucier encoded them using a Sylvania Vocoder rendering music and speech into abstract electronic sound.

Sylvania's vocoder consisted of an array of components: a telephone receiver that registered vocal input; a spectrum analyzer able to sort and filter sonic frequencies; a pitch detector that determined the basic pitch of the auditory input; a voiced/unvoiced detector that distinguished (voiced, pitched) sounds produced by vibrating vocal chords from (unvoiced, noise) sounds produced solely by the mouth, lips, and tongue; a digital encoder that translated this information into binary pulses; a digital decoder that translated the code back into auditory information; and a spectrum synthesizer that used this information to recreate the original input. (Cox, forthcoming, p. 8)

If we play in to the fantastical aspect of this piece, one can understand why the vocoder was used: purely electronic signals are transmitted through space and time more swiftly, and would therefore reach future listeners (who are presumed to have access to a tool with which to decode these signals) more quickly and clearly. In fact its original creator, Homer Dudley (a telephone engineer at Bell Labs), designed a first version of the vocoder in 1928 as a solution to a problem raised by long-distance telecommunication. The problem was how to transport broadband speech signals with a frequency range above 3000 Hz across transatlantic telegraph cables with a 200 Hz bandwidth.

The act of compression carried out by the vocoder, in which speech and music are transformed into electronic sound patterns, is in a sense similar to the act of encapsulation of any time capsule. »In psychoanalytic terms, the vocoder subtracts 'the word' (sense, meaning, signification) and leaves 'the object voice', the material flow of vibration, frequency, and sound.« (Cox, forthcoming, p. 15) As in the Crypt of Civilization, we are only guaranteed a permanence of that which is material.

The Golden Record

In 1977, the NASA launched two twin spacecrafts into outer space. Voyager 1 and 2 carried in them something without precedents in the history of space travel: the Golden Record, a 12-inch gold-plated phonograph record with representative sounds and images from Earth. This "interstellar message" was put together by a committee chaired by Carl Sagan, with the idea of communicating the story of our world to extraterrestrials. On the record one can listen to greetings in 55 different languages (for example »Hello to the residents of the far skies« in Persian), sounds that represent human life on Earth (footsteps, heartbeat, laughter, fire, speech, morse code, ships, kiss, mother, child, etc.) and an overview of Earth's music (Blind Willie Johnson, Pygmy songs, Bach, Javanese gamelan music, etc.). The most expensive record in history is probably now floating somewhere beyond our solar system. Its memory of life on Earth is waiting to encounter an ear that will make sense of it.

2. A SONIC TIME CAPSULE

Hearing gets to places where sight cannot. Ears see through walls and around corners. When something is hidden, sound will reveal its location and meaning. Make a list of all the sounds you can think of that come from hidden places, sounds that are made by objects you have never seen. (Murray Schafer, 1992, p. 24)

Listening is one way we have, as sentient beings, of connecting with our surroundings and ourselves. Sounds are always in movement; we cannot stop them, frame them, or pin them down. So one as a listener must always be listening, following (by being ahead and behind at the same time) the sounds in which we are, and are in. One is thrown in to this current at birth and therefore death is the only form of silence we will know (although the ear is the first sense to develop and the last to depart). Can you think of a sound that is still? Is it still sounding?

Sounds are the surface effects of everything that is happening so listening must take place in the present continuous. Sounds are created by something different in nature to them, yet they are somehow related to the object which they are the effect of. But where is the sound of my clap when I bring my hands together? To the naked ear, sound is an invisible effect of something often times visible. However, as brought forward in Murray Schafer's words, sound can reveal even that which is hidden. It would thus be reasonable to consider sound on its own, independently from its "origin", as an in-between which carries meaning in itself.

It is what is expressed in its independence that grounds language and expression— that is, the metaphysical property that sounds acquire in order to have a sense, and secondarily, to signify, manifest, and denote, rather than to belong to bodies as physical qualities. (Deleuze, 1990, p. 166)

Through listening to what surrounds us we can discover the intimate pulse of a place, or as Kenneth Patchen says in one of his painted poems: »what the story tells itself when there's nobody around to hear it.«

Listening to the present is the task we have set out for ourselves in making a sonic time capsule. The present is something hidden because it is precisely that which is continuously stealing itself away from representation.

The present is »the instant without thickness and without extension« an unlimited movement ceaselessly subdividing itself into past and future (Deleuze, 1990, p. 164).

Listening is what connects us to this finite instant and keeps us in time and on time so in a sense we are always listening to the present. However what we are hoping to do is to make explicit, through a collective listening effort, those sounds which express the present we exist in. Listening to the present is compiling the sounds that define it, the rhythms that articulate it and locating those sounds in which we feel the rarity and wonder of its singularity is conveyed.

What is our time, and how does it differ from other times? What kinds of persons have we become? How can we judge good and bad? What can we hope for? But the task of historical investigation of our present is to diagnose the singularity with which each of these questions presents itself at any historical moment, and in doing so to reveal the peculiarity of the dilemmas through which our own world presents itself to us. (Rabinow and Rose, 2003, p. 21)

Questions such as the ones listed above might point us in the right direction and help us get started. This is the first step in making the time capsule — deciding through active listening1 — what aspects of the present we consider significant and what their sonic expression is (especially for those sounds which have not been sounded before, that are only sonorous in the mind's ear) . The methodologies we can use for this are innumerable. These could include soundwalks, sonic meditations, field recording excursions, deep listening exercises, silent retreats, list-making, question and answer games, improvisations cued by specific parameters, etc. The specific actions will be determined by the participants depending on their background and interests; this should be a cooperative gathering conditional on the initiative of each individual.

In this first stage we must keep in mind that »The attitude of the listener plays an important role in this matter: even the familiar place can reveal itself in a completely new way when listened to carefully.« (Uimonen, 1999, 23) To become a tourist in our own soundscape can allow us to detach ourselves from the functioning environment in order to gain auditory perspective. Furthermore, the time capsule allows us to travel a conceptual distance that will help us intensify this perspective. By imagining that the receiving end of our sonic message is a distant unknown being, we are forced to step outside of our self and our time and convey our experience of these in their uttermost strangeness. If each participant embodies this fantastical distant listener as an alter ego, we might rid ourselves of our familiarity with the present and begin to listen to it and perform it with wonder. This temporal distance can be imagined as a space and »Such a space is necessary for us to begin to re-imagine these problems— it is the space for what might be called freedom in thought: a virtual break which opens a room, understood as a room of concrete freedom, that is possible transformation'.« (Rabinow and Rose, 2003, p. 21)

The second stage is about performing the contents and staging the burial of the time capsule. The previous part can be considered as a rehearsal or preparation for this final part. Through the listening exercises and discussions, decisions have been made regarding what the contents of the sonic time capsule should be. That process can be thought of as the generation of a score that will then be performed. It would be interesting to create a physical record of this collective compositional effort in the spirit of Alvin Lucier's instructions in order to summarize what occurred during this stage. Then others could use it as a catalyst, in the way his instructions inspired us. And in fact this is the type of material we would like this manual to grow with.

The performance of the contents should take place where the time capsule will be buried, as this is the time capsule's funerary ceremony. It would be recommendable to seek out a remote and isolated location for this activity, one not subject to health and safety regulations, and removed from the constraints of daily routine. A deep hole, adequately sized to fit the time capsule (the container will have been selected previously) , should be dug in the ground. The performance and burial of the time capsule should be treated as a solemn yet festive happening; it will be up to the group to decide how to adorn the particularities of this occasion.

Now the moment has come for the participants to encircle the cavity and become performers. The surrounding environment with its sounds is at once the stage and the backdrop for this moment. The performers are improvising and paraphrasing the present and in so doing, expressing the contents the time capsule will contain. Instruments, voice and live manipulation of field recordings are revealing the sounds of our present in this embrace with the instant. An event is in the making.

The actor or actress represents, but what he or she represents is always still in the future and already in the past, whereas his or her representation is impassible and divided, unfolded without being ruptured, neither acting nor being acted upon. It is in this sense that there is an actor's paradox; the actor maintains himself in the instant in order to act out something perpetually anticipated and delayed, hoped for and recalled. (Deleuze, 1990, p. 150)

Now the contents have been performed, and the hole shall be covered. But what exactly should the time capsule contain? What object can congeal against time that which is expressed in a fugue from time? How shall we reify that which transpires?

It is this insistence on the living deed and the spoken word as the greatest achievements of which human beings are capable that was conceptualized in Aristotle's notion of energeia ('actuality'), with which he designated all activities that do not pursue an end (are ateleis) and leave no work behind (no par' autas erga) , but exhaust their full meaning in the performance itself. (Arendt, 1958, p. 206)

- 1. »Active listening is the grasp, the ability to perceive the structure as it's happening: but not by describing it to yourself, because if in fact that's what's happening, you're missing the sensual aspect of the sound, and I think that happens very often. With some balancing, you can listen actively and have the sensual aspect, simultaneously. But if you add describing, as it's going, then there's loss.« (Oliveros and Maus, 1994, p. 182)

Bibliography

Altman, R., 19 92. The material heterogeneity of recorded sound. In: Altman, R., ed. Sound theory sound practice. New York: Routledge.

Arendt, H. , 1958. The human condition. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Ashley, R. Sleeve notes to Lucier, Alvin, 2002. Vespers and other early works. New World Records. 80604-2.

Augoyard, J., and Torgue, H. eds., 2005. Sonic experience: a guide to everyday sounds. Translated by Andra McCartney and David Paquette. Montreal: McGill-Queen' s University Press.

Bartlett Haas, R. ed., 1973. Reflection on the atomic bomb: volume I of the previously uncollected writings of Gertrude Stein. Los Angeles: Black Sparrow Press.

Bartlett Haas, R. ed., 1974. How writing is written: volume II of the previously uncollected writings of Gertrude Stein. Los Angeles: Black Sparrow Press.

Cox, C, forthcoming. Alien voices: Alvin Lucier' s North American time capsule. In: Higgins, H. and Khan, D., eds. Mainframe experimentalism: early computing and the foundations of the digital arts. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Deleuze, G., 1990. The logic of sense. Translated by Mark Lester with Charles Stivale. London: Athlone .

Durrans, B., 1992. Posterity and paradox: some uses of time capsules. In: Wallman, S., ed. Contemporary futures: perspectives from social anthropology. London: Routledge.

Hudson, Dr. P.S. The "Archeological Duty" of Thornwell Jacobs: The Oglethorpe Atlanta Crypt of Civilization Time Capsule. [online]. Available at: http://www.oglethorpe.edu/about_us/crypt of civilization/history of the crypt. asp

International Time Capsule Society. Eight tips on how to organize a time capsule, [online] .

Linenthal, E.T., 1997. Time Capsules: History goes underground. The Journal of American History, Vol. 84, No. 3, pp. 1018-1024. Available through: JSTOR [Accessed 31 May 2012].

Lucier, Alvin. North American Time Capsule. Available at: http://www.ubu.com/sound/extended_voices.html

Morris, L., 2001. The Sound of Memory. The German Quarterly, Vol. 74, No. 4, Sites of Memory, pp. 368-378. Available through JSTOR [Accessed 17 April 2012].

Murray Schafer, R. , 1992. A sound education: 100 exercises in listening and sound-making. Indian River: Arcana Editions.

Murray Schafer, R. , 1994. The tuning of the world: our sonic environment and the soundscape . 2nd ed. Rochester: Destiny Books .

NASA. What is the Golden Record? [online] Available at: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/golden-record/

Oliveros, P., 1974. Sonic meditations. Baltimore: Smith Publications .

Oliveros, P., and Maus, F. , 1994. A conversation about feminism and music. Perspectives of New Music, Vol. 32, No. 2, pp. 174-193. Available through: JSTOR [Accessed 24 March 2011] .

Rabinow, P. and Rose, N. 2003. Foucault today. In: Rabinow, P. and Rose, N., eds. The essential Foucault: selections from the essential works of Foucault , 1954-1984. New York: New Press .

Sauer, T., 2009. Notations 21. New York: Mark Batty.

Stein, G., 2004. Tender buttons. Minneola, N.Y.: Kessinger Publishing.

Truax, B., 2001. Acoustic communication. 2nd ed. Westport: Ablex Publishing.

Uimonen, H . , 2002. Cognitive maps and auditory perception. In: Jarviluoma, H. and Wagstaff, G., eds. SoundScape studies and methods. Helsinki: Finnish Society for Ethnomusicology .

Vikman, N., 20 02. Looking for a 1 right method - approaching beyond. In: Jarviluoma, H. and Wagstaff, G., eds. SoundScape studies and methods. Helsinki: Finnish Society for Ethnomusicology.

Weiss, A.S., 1993. Valere Novarina between the Theatre of Cruelty and Ecrits Bruts . The Drama Review, Vol. 37, No. 2, pp. 80-94. Available through: JSTOR [Accessed 13 March 2012].

Westerkamp, H., 2002. Linking soundscape composition and acoustic ecology. Organised Sound, an International Journal of Music and Technology, Vol. 7, No. 1. Available at: https://www.sfu.ca/~westerka/writings%20page/articles%20pages/linking.html, London, 2012