It is impressed in the body

More than a year and a half passed before the concrete rooms of Kraftwerk, home of the first nightclub in East Berlin, could resonate again. The brutalist building in Köpenicker Straße opened at the end of September to host Metabolic Rift, a new project of the legendary festival Berlin Atonal that will run throughout the month of October. Besides a concert series, Metabolic Rift includes an exhibition in the main hall and in previously unused spaces, aiming to convey a »feeling of overload, of intense and transformative musical and artistic experiences«.

For a moment, I think about the chattering teeth of a fearful animal in hunting season

The title refers to the Marxist notion of rift between industrial society and nature, and to the flows of energies and materials that humans regulate between the two. The formerly most important powerplant of East Germany becomes not only an architectural manifestation of this relationship but also the infrastructure of a metabolism in itself, composed of chain reactions and intercommunicating vessels.

Scriabin’s mystic chord

As our small group descends the stairs of the empty nightclub Tresor, I squint to adjust my vision to the dim light. The door opens to a dark tunnel, at the end of which a glowing monitor welcomes us: a woman swings a knife at the ground and a soft voice calls, repeatedly and soothingly –»Baby«….

A yellow light illuminates an adjacent room, and we follow it as the screen blackens. A block of ice melts slowly under a rusty lamp, and while I observe the water expanding on the concrete floor, Pan Daijing’s voice reappears, accompanying the second video of her multichannel work Seal. I see someone covering the eyes with the arm, liquid drips from the fingertips and run down the forehead; the word »sweat« hisses through the psychoacoustic installation as incantations that layer and precipitate one upon the other at increased intensity. No one is moving until the binaural sound is swept away by a cloud of fog.

The light beyond the cloud indicates our way further, and I move reluctantly, tempted to perceive again that oozing atmosphere. Along the journey, I will learn to adjust my relationship to a space where I used to wander and lose myself freely. As I meander through the darkness, the sequential materialization and eclipse of the artworks not only guides me, but also dictates the rhythm of my experience – a linear progression of impulses pushing me through the inscrutable bowels of the building.

I suddenly find myself in the main pavilion of Venice Biennale, eight years ago

A series of quick rattles cut the suspended energy of Seal’s incantation. I walk towards the hammering sounds, but all I can is see is six iron pots, most of which hang at the entrance of the next hall. From beneath, I notice that a bass transducer hits each one with a different note – constituting, as I read, Scriabin’s mystic chord in tribute to enslaved people, who used similar pots to absorb and conceive the sounds of their clandestine gatherings. My curiosity towards the clanging equals the discomfort of my temples, slightly drilled by these frequencies. For a moment, I think about the chattering teeth of a fearful animal in hunting season – or maybe of a person, considering the reference that the artist Jeremy Toussaint-Baptiste entails in his installation Devo.

Sign of life and Chicago House

Further on, in front of the stairwell that leads out of the basement, I hear for the first time a sign of life in these industrial interiors, a female voice. I stretch my neck to look for a sign of a physical presence – framed by the coil of the balustrade, a hand invitingly articulates in the air the singing, which now, more open and deliberate, resonates insistingly in the echo chamber of the staircase. As I march up, a slight pant fills my chest and ears, muffling the intonations and our footsteps.

We finally reach the upper floor to gather around the singer, who keeps clicking her tongue, smacking the lips, humming a vague melody. I suddenly find myself in the main pavilion of Venice Biennale, eight years ago, in front of Tino Sehgal’s performers. Their quirky and intimate sensibility (both sonic and physical) was a response to the 20th century’s illusion of humans to master the world, the »philosophy of solitude«. Now, while the singer in front of me opens a door, I wonder if she will show us a way out of this ghost-train system.

Natural light falls faintly from the roof windows on a deserted hall and the perception of space and light makes us gasp in a slightly liberatory breath. The legendary Killasan sound system towers in the middle like a black wall, and as I circumvent it to look at a white cloth close by, Hieroglyphic Being’s distinctive sound slowly fills the room. The syncopated hi-hats typical of Chicago House music seems to be enveloped in an ethereal cloud of chimes and vibraphones, that are soon blended with dub heavy-bass lines at the limit of distortion. I can feel the vibrations on my sternum, on my skull, expanding from the floor under the feet, yet my ears are not overwhelmed, I can even hear the few chatters behind me.

Slowly a tube man rises from what I thought to be a cloth and dances sinuously between us and the speakers. I can’t but surrender to the nostalgic fantasy of collective dances, and I ask myself if its mesmerizing fluidity is also affected, like me, to the sonic massage of the vibrations. The music fades, the air-fans slowly cease to buzz, and the sky dancer falls on the ground with a puff.

Am I in a cemetery of past desires and dream’s debris?

Parking lot rave

The installation Visitant: no dancing by Jamal Moss and Cyprien Gaillard opens indeed a way out: the wide concert halls of Kraftwerk is animated by a rather different rhythm than that of the past hour. A soft humming floats in the air from different alternate sources and I wander after them until I am attracted to a drone in the mezzanine, where I see eight illuminated disks.

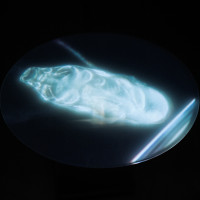

The videos of floating translucent organisms, monocellular and autopoietic systems, are paired each with a speaker and their own distinct sound, created by Vladislav Delay in collaboration with Adameyko Lab. I walk in between this dense orbit of palpitating voices, trying to decipher their individual nature. Some tinkle, others knock, tick and drop, but it is impossible – almost arrogant – to try to dissect one out of this vibrating tissue. Exiting the dark hive back to the main hall, I recognize the distant beats of the Killasan and stepping down to the ground floor, I capture the last rattles of the Devo installation. In the second act of Metabolic Rift, sounds and artworks seem to accumulate and dissipate freely in the open spaces that activate alternatively in quasi-organic pulses.

In a corner, several car wrecks lie under dirt and dry leaves. Voluminous speakers occupy the boot trunks, as traces of a lifeless parking lot rave. Garish led lights mark the incipit of Lyra Pramuk’s ethereal soundscape, and beyond the broken windows and deflated airbags, I see the remnants of a party scattered in the interiors of the burnt skeletons.

The music, looping in waves of higher pitches, climaxes to a celestial and eerie ecstasy. Its mellow spectrality is hauntological: am I in a cemetery of past desires and dream’s debris? The title This Too Will Pass suggests indeed a eulogy.

A club is a space for explorations of different relational sensibilities and their in-betweens

Impressed in the body

As sounds and impulses move and mingle, sometimes guiding and sometimes eluding, it is clear to me that the whole exhibition is a process of transformation between the once alive, the decaying, and again the alive. The building itself is a metaphorical organism, whose enzymatic processes are activated by principles of intensification, exchange, transmission and release affects, sensorial stimuli and sonic remembrances. Somehow, these dynamics do not differ excessively from the habitual purpose of the building: a club is a space for explorations of different relational sensibilities and their in-betweens, for transformation and exchange. The forced adaptation to an art show able to preserve and reconfigure the fluidity of the club’s subjective and sonic susceptibility gives us a glimpse of the unexplored possibilities that these music venues could offer. From a curatorial perspective, I realize that I have rarely seen a similar approach to the aural and its (im-)materiality in the context of exhibitions. Not only does it give to artworks a certain operational autonomy but, most importantly, it is not afraid to let sounds develop and overlap. On the contrary, it encourages the very nature of acoustic waves to float, expand, react in uncontrollable combinations, and disperse.

In this sense, the actual source of the experiential landscape I am walking in is the interaction between the different sensorial element of the exhibition, and between object and subject. After all, also my ’metabolic existence’ is a net of interactions between object, subject, and their inbetweenness. The contingencies of sound and art experiences are anything but a mechanistic process: quite the opposite, sound perception relies on the space it inhabits and it depends on the idiosyncrasies around the event, mingling with intersubjective sensibility.

After I have exited, even the dull light of an Autumn afternoon is bright and slightly disorienting. The humming of the cars on Köpenicker Straße seems now clearer and more distant than before. The recollection of the past two hours is somehow impressed in the body, as if after a tactile experience. And indeed: does the process of listening – often confined to a limited and pre-conditioned set of positionalities – not just occur through psychological or intellectual mediations, but also through a materiality that remains in the memory of our full sensorium?

The exhibition Metabolic Rift was part of the yearly festival Berlin Atonal and took place 25 Sep.-30 Oct. 2021