»I want to examine sound's relationship with as much of the world as possible«

MOPS exists to examine as much of sound's roles in the world beyond music as possible, so if I can use a recording to bring attention to some aspect of sound in the world that I haven't covered before, then I want it in there, says curator, John Kannenberg

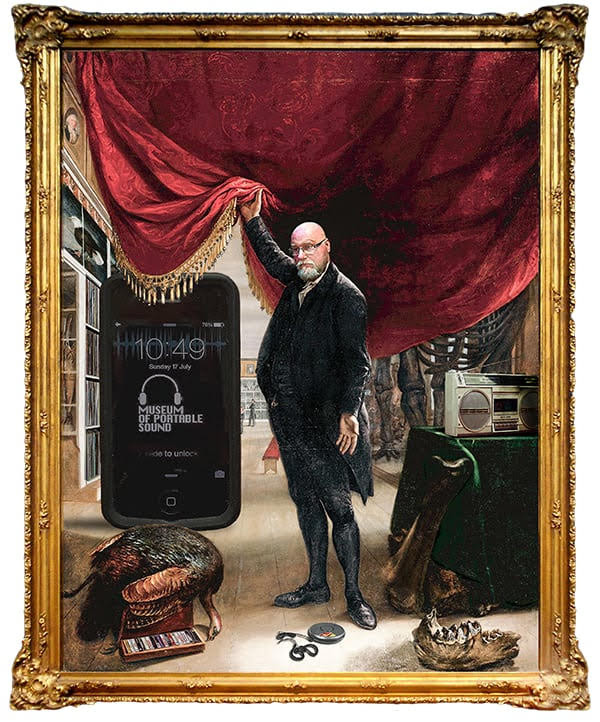

On the list of things you probably haven’t experienced much during the pandemic is a visit to a British Museum but here’s your chance – regardless of the world situation: Museum of Portable Sound is a physical museum dedicated to collect, preserve and exhibit sounds as objects of culture raising debates on digital materiality, the bias of sound and sound as cultural heritage. Until the pandemic, visits have been purely physical but during the last year, it has been possible to do a personal guided tour around the museum with the curator, John Kannenberg, via Zoom or Google Meet. I met with Kannenberg for a tour around the museum and an interview. Upon my arrival I was informed that I was visitor number 1894 – or rather visit number 1894 since tours vary a lot in size and the last one included 117 people.

»So then I had about two weeks to put an actual museum together«

Thank you for a the tour around your thought-provoking museum. Can you give a brief introduction to the Museum of Portable Sound, which collections you have and how you actually visit it?

»MOPS began as a side project at the end of the first year of my PhD. I was studying the sounds of physical museums, and at the same time, I had been thinking about how it might be possible to create a museum of sounds, which had always been thought to be impossible. I had the idea for a museum of sounds without a physical space for about a year before I actually built it. I only put it together because I was invited to give a public talk and the organisers asked for more than one possible talk. I pitched two ideas, one of which was a Grand Opening Ceremony for the Museum of Portable Sound, and everyone agreed it was the stronger of the two ideas. So then I had about two weeks to put an actual museum together.«

Before the pandemic, he used to require that any visitors would meet him in person, bring their own headphones, and listen to the museum on his phone

Curating a museum of sound

In the museum, there's a broad variety of sounds collected in various ways. Can you tell a little about how you collect sounds, who records them, and how you choose which sounds to exhibit?

»One of the things that keeps MOPS unique as a contemporary sound project is its exclusivity. The trend in sound projects for a while now has been things like crowdsourced online sound maps – everything's open, and that's been great – but it also means that now that it's a trend, it's become an expectation,« says John Kannenberg

»When MOPS first began, all the sounds were recordings I had made myself. I had a fairly large collection that I knew could sparsely fill the four main 'museum-like' topics I wanted to cover. So once MOPS was up and running, it made sense to me for its sound objects to almost exclusively be things I've collected myself.

»I wanted MOPS to be unique, and to explore ways of making recorded sound feel ‘museum-quality’ in a post-MP3/streaming world«

As time has gone on, I've invited other people to contribute recordings, but always because I know they have something specific that I would like to have in the museum. The museum has already grown to a size that's overwhelming for visitors, and being very selective about what gets put in the museum is partially a way to keep it focused and manageable. But also, I want the contemporary field recordings in the museum to not be available anywhere else, and it's difficult to find other artists making field recordings who are ok with something they recorded not being streamable or downloadable on the internet.«

Exclusivity on an iPhone 4S

The museum's sound objects are primarily field recordings that John Kannenberg made over the past twenty years or so. The recordings are stored as digital files on a single mobile phone – an iPhone 4S – and, before the pandemic, he used to require that any visitors would meet him in person, bring their own headphones, and listen to the museum on his phone.

»I wanted MOPS to be unique, and to explore ways of making recorded sound feel ‘museum-quality’ in a post-mp3/streaming world. So keeping the contributors to as small a group as possible, and not distributing the sounds anywhere online, is part of what gives the material this aura of belonging in a museum rather than just any old FLAC file you downloaded.

The sounds in the collections are only accessible from this one mobile – they're not available on a website or an app. That's why I made people meet me in person. I specifically didn't want to distribute the sounds online, because I wanted visitors to make an appointment with not only me but with themselves, to sit down and listen. And I didn't want them to be able to delete the museum's app from their phone the first time they needed more space for photos.

I was also curious about Freud’s toilet in Vienna – which turned out to have a much more authentic and strong toiletty sound than his water closet in London

It focuses as much as possible on non-musical sounds. What I mean by that is sounds that a general museum-going audience (not an audience of 'sound artists' or composers) perceive as being non-musical. Unlike anyone who's ever idolised John Cage, general audiences are very comfortable with the idea of there being non-musical sounds, so once I decided to accept that concept it became much easier for me to zero in on what the museum should be about: the role of sounds across every aspect of nature, science, and culture.«

There are 30 galleries at the moment, and these are organised under four main topics: Natural History, Science & Technology, Architecture & Urban Design, and Art & Culture.

»I chose these because they're all historically typical ways that museums have organised the world, and using these categories help visitors relate to the sounds as museum objects. So within these four main topics are galleries dedicated to things like Weather & Water, Transport, Food, Underwater Life, Rituals & Events, the History of Audio Recording, etc. This approach is something you can see pretty clearly if you look through the MOPS Instagram feed or Twitter account where I discuss sound across culture and history beyond what's represented by the field recordings on the mobile.«

»It's probably the closest I've ever come to capturing the sound of pure human joy«

Phonoautogram, wax cylinders and Freud’s toilet

The museum collection counts almost ten hours of sounds, so Kannenberg sent me a link to the visitor’s guide before we met. I chose to hear Gallery 8: London Museums including a wax cylinder recording from 1888 on Crystal Palace with a choir of 400 people singing Händel, and the Escalators at Tate Modern (approx 20 mins). I also went for the Bonus exhibition Recent Acquisitions including amongst others Andy Warhol in the supermarket, and the first pirated mp3 ever. I was also curious about Freud’s toilet in Vienna – which turned out to have a much more authentic and strong toiletty sound than his water closet in London. One of the most interesting sounds, though, was the first-ever recording of the human voice from 1860 made by the little known Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville from Paris. This was made 17 years before Edison did his first recording on his phonograph. This recording was a visual interpretation of sound, but the technology to play it wasn’t invented until 2008. I was introduced to the story of this sound followed by the words »Be prepared to be unimpressed!« I’ll let it be up to future visitors to make this judgement.

»The third sound on my list is the sound of my wife eating Pop Rocks® candy for the first time«

Do you have a top three of personal favourites?

»I do! There's actually a Guided Tour in the museum of my personal Top 40, but my favourites keep changing all the time.

There are two sounds I have that are actually tied for first place to me – one funny one and one serious one. The funny one is the sound of me falling off a camel next to the Great Pyramid in Egypt, which almost never ceases to get a laugh out of people. The serious one is a sound I recorded while on holiday in San Francisco in 2008, and accidentally stumbled upon the Pride Parade which I had no idea I would be in town for – and it just so happened that this was the year that California voted to legalise gay marriage, so it was a particularly emotional Pride that year. I happened upon the parade by following the sound when I left my hotel that morning, and suddenly I turned a corner and was standing in the middle of Pride – right when a lesbian marching band paused and played their rendition of »Chapel of Love« and the crowd let out a roar. It's probably the closest I've ever come to capturing the sound of pure human joy, says John Kannenberg with a smile.

»The third sound on my list is the sound of my wife eating Pop Rocks® candy for the first time. I had her hold contact microphones to her cheeks to capture the sound inside her mouth, and it's pretty wonderful. We filmed it, and the video is part of the MOPS video archive on our YouTube channel.«

»I think MOPS is a really difficult project to pin down to a single category«

Science, art or Gesamtkunstwerk?

When you showed me around in the museum, I was just about to confuse you with a scientist since the Museum Of Portable Sound (MOPS) can be of great interest to – and importance for – historians both today and later. Amongst other things, contextualizing the history of the first pirated mp3, the technological historical aspects of the development of the phonograph, and the cultural history of toilets. But it now seems to me that your mission is artistic – is this correct? If so – how does the artistic project MOPS differ from the historical/scientific project MOPS?

»I think MOPS is a really difficult project to pin down to a single category because it's kind of – at least to me – a quintessentially interdisciplinary piece of work. It began as an art project because I'm an artist by training, but it developed out of 15 years of study and research, both in and out of academia.

Because I was interested in museums beyond just art museums – like I'm interested in sound beyond just musical sound – it meant that I'd set MOPS up with these four main categories, only one of which was art-related. I wanted to examine sound's relationship with as much of the world as possible, so suddenly I was looking at sound in archaeology, in science, in architecture, in mythology, in pop culture, in sociology, in military history, in anthropology, in zoology – in practically everything I could think of, and all the while trying to look beyond music – which is the simplest way to think about sound.

But then that folded back into the artistic aspect of the project: it also became a project about me performing museum expertise. I wasn't curating other artists' work, I was curating sound recordings into scientific categories in order to research how sound is embedded throughout our entire experience of the world and acting as if I knew and understood it all. But because I'm interested in humanising museums as institutions, I let the limits of my knowledge and my mistakes become part of the performance, especially on social media.«

Recorded sounds are usually collected by libraries and archives rather than museums

Sounds as cultural heritage

You hold a PhD with the title: ‘Listening to Museums: Sounds as objects of culture and curatorial care.’ What is the current state of sound as an object of culture? I know that some crafts are on the UNESCO list of cultural inheritance – do we have the same acknowledgement of sounds?

»No ,we don't, and it's really a shame. Currently, UNESCO protects 'intangible cultural heritage', which it defines mostly as preserving instructions on how to conduct rituals such as dances, songs, etc. It's a very music-centric viewpoint, and also, in my opinion, a colonialist one – it's a policy and a definition that was very much set up with good intentions but also somewhat reinforces the notion of non-’western’ people as incapable of maintaining control over their own ceremonies and practices.

But sounds are also considered intangible, and the idea of soundmarks – local sounds that add to the acoustic identity of a region, popularised by Canadian composer R Murray Schafer in the 1970s – seems tailor-made to the idea of 'intangible culture' in many respects. But this is more evidence of how museums and cultural institutions are very sound-shy and unsure of how to deal with sounds as objects. Recorded sounds are usually collected by libraries and archives rather than museums, and even then those archives are usually filled with two things: music and interviews. While there may be non-vocal or non-musical sounds in the collection, often they are sidelined because of the bias towards music as the default 'best' sound. I would love if MOPS could help to try to change this attitude.«

»Birds don't 'sing' for the benefit of human aesthetics«

Political discourses and the bias of sound

I reckon that there aren't many museums that work with sounds as objects of culture worldwide? Is an initiative as MOPS a political priority when it comes to funding and acknowledgement as an international institution of cultural heritage?

»There are more and more museums that are beginning to get involved with sound, but again there is a huge bias towards musical sound. Much of what we think of as 'Sound Art' is essentially music being played in a gallery space, so although sound has had an increased presence within art museums over the past two decades, much of it is simply what's also called 'experimental music' rather than sounds that have been museum-ified (turned into museum objects by actively documenting and interpreting them within a museum context in the same way that museums interpret physical objects). That type of activity mainly only happens in science museums, or in natural history museums with things like bird calls or whale vocalisations – which are unfortunately viewed as music rather than what they truly are, which is the language of communication within the animal community. Birds don't 'sing' for the benefit of human aesthetics, they vocalise to communicate with each other. But it's easier to get humans interested in them by simply claiming they're music.

This is definitely part of the MOPS mission, to help more museum professionals understand the ability for sounds – particularly non-musical ones – to be taken seriously as objects in their own right, not just as source material for a DJ to remix during a Friday Late event.«

Sound, Please! and the future of MOPS

MOPS is in other words in the same situation as many other cultural institutions that don’t live up to the ruling political discourses of art, cultural heritage and priorities. John Kannenberg is in fact running the show all the way from curating the sounds to designing the Gallery Guide, research and social media. There’s an international board of directors, but with no budget, it's difficult to get them involved in the day-to-day work of producing content.

»I did have an intern for a year, who was awesome and helped out on a lot of projects, but I couldn't afford to pay her anything – she insisted on working for free because she wanted the experience – so eventually she had to move on. The best way for people to get involved is to book a visit to the museum and share their thoughts on it with me because I always listen very closely to feedback and often change what I do based on what people suggest.«

Do you have a future plan lined up for the years to come – or do you have a dream scenario for the museum in the future?

»I have a lot of future projects in the works at the moment, but since I'm the only staff member and the museum has no funding other than visitor admission fees, it is really difficult to see all of them through.

In the immediate future, I'm finally finishing up cataloguing all of the books & PDFs I've collected related to the various topics MOPS explores, and will be publishing the contents of the MOPS Research Library in the autumn. We have a new temporary exhibition coming up very soon called Sound, Please! which features the work of Treg Brown, the sound editor responsible for making the sound effects for all the classic Warner Brothers animated cartoons,« says John Kannenberg who contributed to a chapter to the upcoming Oxford Handbook of Archaeology Museums which is about the history of sound in archaeology museums that includes a case study of the MOPS Archaeology Gallery.

In November 2021 Kannenberg organized the first ever Museum of Portable Sound Conference: An online academic conference featuring paper presentations, audio papers, and essay films.

»I'm also writing the Museum of Portable Sound Guide to Museum-Quality Field Recording, which isn't actually a field recording manual but more of the story of how and why I make field recordings and display them in a museum context – but it also will cover a lot of my activities recording the sounds inside other museums.«

Is MOPS a museum, or rather a piece of art in itself?

»It's both! And it's probably other things too.«