The City that made Noise into History

It must be shouted loud enough through a megaphone to be heard over all Copenhagen’s streets and alleys, boulevards and avenues, squares and marketplaces: The Sound of Copenhagen is an exceptionally successful exhibition. It is captivating, engaging, and enlightening, and it helped me renew my auditory attention to the city I have known all my life and have lived in for most of my life.

The Sound of Copenhagen is an exceptionally successful exhibition

Moreover, the exhibition is focused and concentrated to such a degree that this very aspect helped sharpen my own concentration as I walked through the museum rooms, with their display cases, posters, artifacts, and sound sources.

The exhibition’s numerous portrayals and conceptions of Copenhagen as a soundscape particularly concern the chaotic era of industrialization and population explosion from 1870 to 1920 – a span of half a century, sometimes extended a few decades backward or forward. The old days simply grew into my ears along the way, as I realized how much the city’s sounds define this period, frame it, envelop it, prolong it – in short, bring it to life.

The sounds, heard primarily through historical recordings in headphones, told both a compelling and disheartening story of the sonic chaos Copenhagen must have been back then. I kept thinking of the people of all ages who lived in the city during that time and who could not escape its sounds, even if they wanted to, simply because moving elsewhere was not an option.

The exhibition’s sonic time travel

Copenhagen’s kaleidoscope of everyday sounds was all-encompassing, from neighboring apartments to the street, from the harbor to the factory. For some, the sounds were perhaps a constant reassuring confirmation that they were in the right place – the noise was a sonic backdrop to a big-city life unlike any other in the country. For others, the sounds were just a circumstance they hardly thought about, simply accepting it as a basic premise. And for yet others, the sounds may have been something quite different: a source of frustration, distress, and powerlessness.

How many lives, one wonders, were poisoned, clouded, and cut short by this sonic backdrop, which at times must have been a veritable hell of noise?

How many lives, one wonders, were poisoned, clouded, and cut short by this sonic backdrop, which at times must have been a veritable hell of noise? We don’t know. But from our contemporary research, we know how damaging noise can be to both body and soul. According to a 2018 article on DR’s website, the WHO has stated that traffic noise is a potentially very harmful factor in any city dweller’s life. If your home is exposed to a sustained noise level above 53 decibels, it constitutes a health hazard. WHO refers to studies showing that such exposure can result not only in stress but also strokes, diabetes, blood clots – and ultimately premature death.

It’s astonishing how many different urban sounds from Copenhagen’s public spaces back then come alive in the exhibition

We cannot say what the decibel level in Copenhagen was in that period, but anyone who has heard horse-drawn carriages on cobblestones knows how loud it can be. So there is good reason to believe that just as traffic noise kills today, noise – including traffic noise – also killed back then.

The posters in the exhibition also report that around 1900 a doctor recommended the municipality replace the road surfaces with more appropriate materials to reduce noise, and that doctors and psychiatrists at the time worried about noise causing »nervous exhaustion«. Unfortunately, the exhibition does not clarify what was meant by »concerned«, or how these professionals defined noise in the first place.

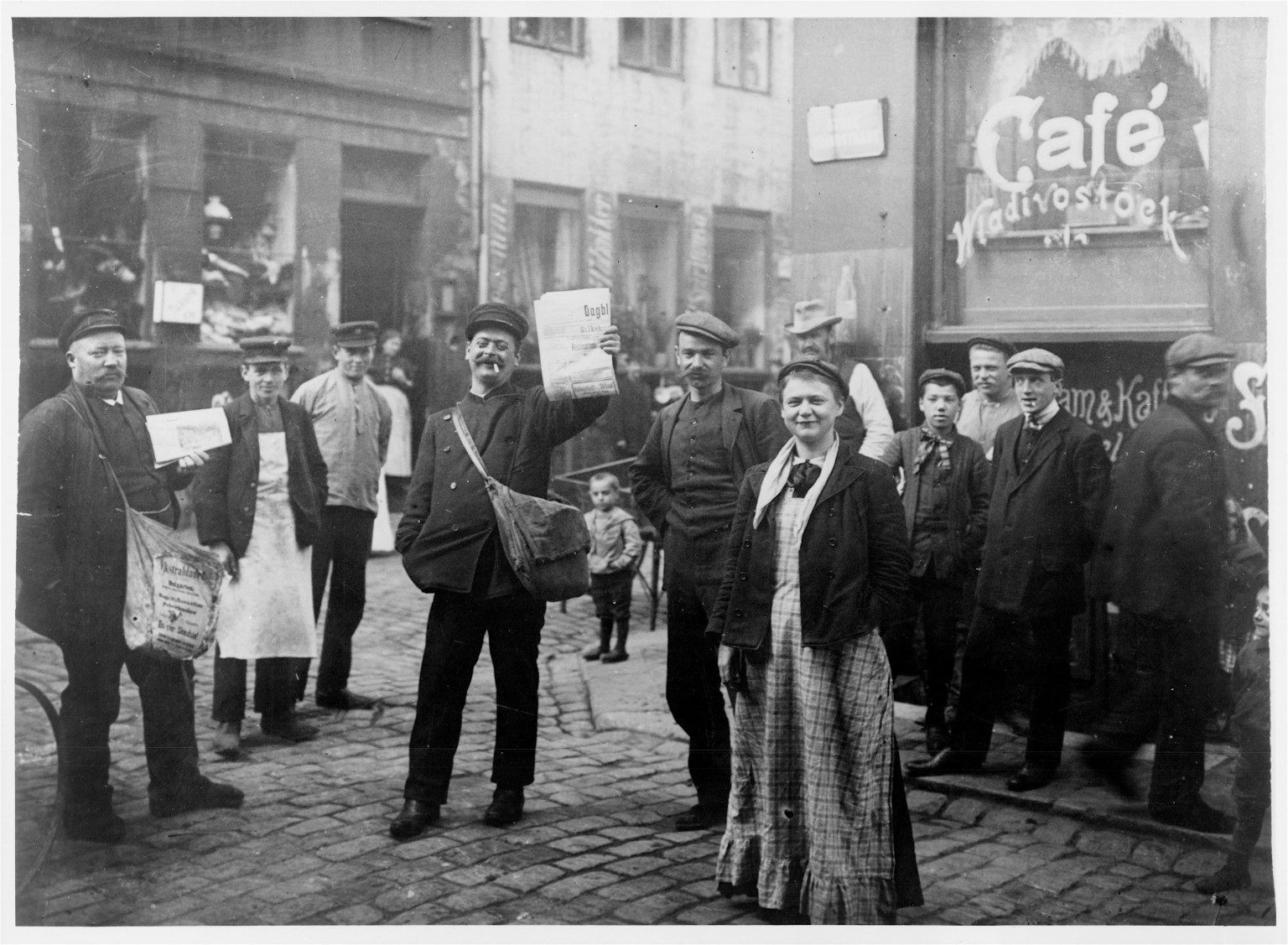

It’s astonishing how many different urban sounds from Copenhagen’s public spaces back then come alive in the exhibition. There are recreations of sounds from many professions, including the night watchmen who patrolled until 1863 and sang a verse every hour, and the street vendors who used so-called street cries to advertise their goods, with the »form and melody« of these cries »handed down through generations«. And boy, could they make noise. Just listen: »Coachmen and sleigh drivers used whip cracks and signal horns to attract customers. Percussion instruments, bells, and gongs were also used briefly to penetrate the noise.«

Soon street vendors changed strategies by using other ways to attract customers and were eventually outcompeted by newspaper sellers, who drowned each other out – and everyone else – with shouts of newspaper headlines, which the exhibition describes as becoming »the sound of the modern city’s hunger for news and connection to the wider world.« At Grønttorvet near Nørreport, women from Amager and many others sold their goods with shouting and gestures. One famous voice from interwar Copenhagen was the fishmonger Dagmar Hansen, who sold fish on the street in Østerbro and became a media personality over the years.

And I haven’t even mentioned the horse-drawn carriages, the horse-drawn and later electric trams, trains, ships, cars, buses, and also the sirens

Oases of silence and conscious listening

The exhibition focuses on much more than those who filled the urban space with their voices. It also tells about the city’s materiality – the pavements and streets that either amplified or muffled sounds. And what about the neighbors? In the densely packed apartments or barracks, often poorly soundproofed, it was a nuisance to have inconsiderate neighbors regarding noise, or for that matter singing and piano playing, and neighbor complaints, as the exhibition points out, became almost a »Copenhagen sport«. And I haven’t even mentioned the horse-drawn carriages, the horse-drawn and later electric trams, trains, ships, cars, buses, and also the sirens, which obviously all left a strong mark on the city’s sonic physiognomy.

As an interesting perspective on noise in Copenhagen at the time, the exhibition highlights the silence that was also cultivated in that period – among other places in parks, schools, and forced labor institutions for the »paupers and petty criminals«. This is an intriguing contrast reminding us that there were, of course, opportunities to seek beneficial quiet – in parks, churches, cemeteries, by the lakes, and so on. Another perspective relates to concentrated listening, where the listener actively seeks out sound rather than being passively exposed to it. At least the exhibition reminds us that 19th-century inventions include the stethoscope, microphone, telegraph, telephone, and phonograph.

The sounds of bicycles, passing voices, and much more suddenly became differently alive and distinct components

The exhibition wisely avoids any attempt to aestheticize the city’s sounds; even music was reportedly perceived as potential noise by those who hadn’t asked to hear it – such as neighbors or passersby. All the more misplaced, then, is the museum’s own press release stating that the city’s traffic noise at the time was like a »constant humming soundtrack«. Tell me: Is noise always music for everyone? It’s not that simple – especially not in the period the exhibition mainly covers.

A new experience of the city after the exhibition

When I left the museum, I walked the short distance from the Copenhagen Museum in Stormgade up Vester Voldgade to City Hall Square. Because I was slightly dazed by all the sounds I had heard along the way, as well as the sounds I had imagined in my mind, walking through the city felt like an entirely new experience: The sounds of bicycles, passing voices, and much more suddenly became differently alive and distinct components in a long historically conditioned story about Copenhagen, where the sounds’ present-day reality mixed in my head with their historicity, which they both were and still are.

The exhibition makes you want to hear and learn more about Copenhagen’s sonic physiognomy

During the walk, I was confronted with other city sounds not considered in the exhibition: those of nature. I was exposed to the not-so-quiet sound of the wind howling fiercely down Vester Voldgade, mixing with the other street noises. Wind, rain, hail, birdsong, and other natural sounds have obviously always been important components of Copenhagen’s soundscape, changing the character of the surrounding sounds – for example, snow often muffles them.

It’s clear that natural sounds are not specific to Copenhagen, but neither are many of the sounds described in the exhibition. The fact that street music as such doesn't play a major role in the exhibition might be explained by the fact that it is a large and complex category, one that stands in contrast to everyday sounds by having an aesthetic dimension. But the absence of natural sounds from the exhibition's themes is striking. Is this a conscious omission that simply hasn't been made explicit in the exhibition materials, or is it merely an oversight?

The exhibition makes you want to hear and learn more about Copenhagen’s sonic physiognomy. Imagine if the museum decided to follow up with another exhibition about the sound of Copenhagen from the 1940s and a few decades onward. The city’s newer sound history would surely interest many, and although we have Else Marie Pade’s meticulous renditions of Copenhagen’s sound as it sounded at the end of the 1950s (in her masterwork Symphonie magnétophonique), as well as numerous feature films and TV series shot in the city during that period, there is so much more to uncover. I keep my fingers crossed.

»The Sound of Copenhagen – Noise, Voices and Silence«, Copenhagen Museum. Opened May 16, 2025, and on view until January 4, 2026. The exhibition is curated by Jakob Ingemann Parby and based on the research project »Lyden af hovedstaden: Støj, nerver og naboer i 1800-tallet« – a collaboration between museum and university experts. Following the project and exhibition, two books have just been published by Gads Forlag: Jakob Ingemann Parby’s The Sound of the Capital: Noise, nerves and neighbors in the 19th century and Pia Quist and Bjarne Simmelkjær Sandgaard Hansen’s »Bondsk i København«.

English translation: Andreo Michaelo Mielczarek