»I love freedom and I know why«

I’ve been thinking a lot about how to start our interview. Besides many questions one topic still seems the most important – the war in Ukraine. But maybe you don’t want to talk about it anymore?

»Actually, I think it’s important to still talk about Ukraine. It’s already been three months since we started fighting and it’s crucial to not stop talking about it. Otherwise it will become a new normal and that is not right. Everybody should scream.«

Your other interviews took place just after the outbreak of the aggression.

»Very soon indeed. It was very difficult for me to talk about it, but I forced myself. If I could have been a voice for Ukraine, even if it was so hard, it was the least I could do. That’s why I didn’t care about my comfort – it’s about the lives of the people.«

»I thought my work wouldn’t be connected to war, that I could abstract from it. Yet the outcome is very dark«

When you talked with the Seismograf Magazine you said that music would be different. Back then you didn’t know exactly how – what about now?

»Now I have a clearer vision, as I’ve started composing again. I’m finishing a piece for electronics which will be performed in MUMUTH – Haus für Musik und Musiktheater in Graz with ambisonic system. In this piece I was working mostly with my voice and different feedback and noise techniques. I also plan to start working on my third album this summer. For months I haven’t forced myself to write, as I didn’t want to associate war with music – the thing that I love the most. It’s psychological, now I don’t even like the place I was at when I heard about the start of the war (hopefully it wasn’t Graz). From then on I was fighting and only now have I started to compose again, very slowly.«

»I thought my work wouldn’t be connected to war, that I could abstract from it. Yet the outcome is very dark. Very disgusting in a way, showing the worst part of a person. Noisy, completely different from what I’ve done before. It’s a surprise for me – not something that I think would turn out. I use human voice a lot, but it’s processed so much it’s hard to tell if it’s human, or 'something in between'. Or like the Russian army – not human at all. It also has a sexual feeling thanks to the use of breathing voices. Music that makes it uncomfortable to listen. To make you feel disgusted and bad in a way. Pushing you through the border. So you can leave these emotions and eventually see the world in a brighter way.«

This pain is deeper

You kind of predicted it in that interview as well. You also anticipated that people who don’t share that experience with you won’t be able to understand your music. How to compose with such a thought in your mind?

»In such a situation you care about everything that happens, it’s your nation. The pain of seeing your people dying. In general, I feel a connection with all the Ukrainian people, it’s hard to explain. It’s unconscious. Even if it’s so sad, I get to understand what it feels like to be Ukrainian, why we are a separate nation. Poland supports us and many other countries do, but in the end you can feel alone. It’s like somebody from your family died and you have a best friend that will console you, but they can’t feel the pain. Same goes with music.«

»I feel it especially here in Austria. Lots of pro-russian moods, especially in Vienna. My University of Performance Arts in Graz supports Ukraine, but they are still very far away from this situation, to be honest. A lot was going on back then: people migrating to the border, searching for the supply for them, posting the news on social media every 10 seconds. Maybe some artist could think about art then, but not me. I was reading the news all the time, I couldn’t sleep, I couldn’t eat, I couldn’t take a shower. Art was very far from me then.«

»In the Ukrainian language we have so many variations of the words pain and sadness but in English it is difficult for me to find analogies«

What do you think about separating the role of the artist and the activist then?

»As it comes to composing the piece that I’ve mentioned for example, I don’t want to make it 'for Ukraine'. Now that everything is like this, I don’t want to add more of it, but rather push the message on a sub-level. The message of my music now is probably the pain, it’s hard for me to 'unite and be an artist' outside the war. Because your whole life is divided into 'before' and 'after' and as it was 'before' it will never be the same as it was before. This pain is deeper and more acute. When you no longer have the strength and power to scream, when there is an impression inside that every cell of your body is pain. In music, I want to show it, but without the program and more personally, to share my pain, my sadness with the listener, my sadness. It is interesting that in the Ukrainian language we have so many variations of the words pain and sadness but in English it is difficult for me to find analogies.) In a more intimate way. For me it’s more about the emotion when you hear it than its program. Plus now that I have some performances I always try to do something: raise a flag, or scream “’ at least. Just to push people back to the situation. So you can expect me to speak to you after the Ephemera performance in Warsaw.«

So your way of performing has changed as well?

»Yes, completely. Now, for me, the speech is also a political protest, where I can draw the attention of listeners to Ukraine. An artist cannot be out of politics now. My performances are especially important to me and they are very emotional. There are songs in which it is very difficult for me to hold back tears because they have acquired a completely different meaning now.«

You started off with some diverse range of concerts: at electronic music festival Hyperreality in Vienna, then in the gallery surrounding Camden Art Centre in London, finally at Berlin’s CTM. How do you anticipate the performance in Warsaw at Ephemera Festival?

»I’m very excited, especially for the fact that it’s gonna take place at dawn, I’ve never performed like this. It is going to be magical and symbolic too – the sun rising meaning surviving the night. The hope. Very meaningful for me in these times.«

»For the evolution of the nation’s spirit, the war did something that normally would take 100 years«

Being a nation

You have lived, studied and worked in Ukraine, Poland and Austria so far, so you have a certain overview of some countries. I’m curious about your opinion on how the music world reacts to the war in your homeland. Do you feel supported?

»I’ve always felt supported in Poland, my pieces were performed here. Also one student concert supporting Ukraine took place there, at the beginning of war. There was one like this in Austria too – a very popular program just to raise the money. The teachers participated as well. But what is more important, I see that we started to boycott Russian culture. Now before every concert I check if there will be a Russian person performing and if they supported the war. We were in such shock that we cancelled some concerts. And we Ukrainians have so many composers, even those never in fashion, like Borys Lyatoshynsky– 'our Mahler', one of my favourite composers. Another point is that the recruitment for universities in the European Union was much facilitated for Ukrainian students. Normally due to legal procedures access for us is really limited. Also male artists, who want to perform abroad, have to ask the Ukrainian Ministry of Culture for permission. All of those take weeks. Of course only girls could get this opportunity – boys were not allowed to leave the country…«

This makes me think of John Object – Ukrainian electronic music artist, now made a soldier. He posts about this abstract experience on his social media and all that makes me wonder what the Ukrainian electronic music community looks like now?

»Here I would like to thank my label Standard Devotion and especially its owners Paul Georg and Maya Baklanova. They all worked in the club Kyrylivska. When the war started they made a compilation to fund Ukrainian artists who needed aid. They also helped girls get to the border, and supported the LGBT community. Our scene really cut up everything from Russia. As for their big names – a really small percentage actually did something. We kept on pushing them to speak up, we tried to get to any magazine, press. And we are united now, we know we have to fight. So I must say I am happy for our scene: lots of musicians record tracks raising money for Ukraine. Some make 'fighting-music' to keep up the spirit. Others turn to peaceful music to let the people relax and have some hope. For the Ukrainian scene and culture all of this did good – we started to appreciate what we already have. We did before, but always thinking that others are better. For the evolution of the nation’s spirit, the war did something that normally would take 100 years. How we understand being a nation, how we unite. At least this is some positive stuff. Now we understand that we have to create, that it is our culture. Actually it’s very beautiful and we have to value it.«

And Ukrainian electronic scene has already been flourishing for some years now whatsoever. Kyiv was expected to become »the next electronic capital« for example.

»Actually, I was performing in Kyiv in the Kyrylivska club just before the war, 13th of February. That evening was very special, we already felt something might happen. Then I learned that in Kyivthat Kyiv all the mainall main foreign embassies left the city. After the event I went to Lviv to see my parents, then I came to Poland and then the war started. A week later. I can’t explain, but subconsciously I’ve felt that before. It was in the air, but I couldn’t believe it would turn out so huge.«

»It’s the call of my life, to create something I’ve never heard before. Even if it may sound a bit cheesy«

Sound art and Nintendo

Let’s talk about the Ukrainian music scene in general now. You are an example of an artist functioning in two environments: electronic, independent and classical, academic. Are these two scenes much divided and separate in Ukraine?

»Yes, actually the same as in Poland, maybe even more. In Ukraine it’s becoming better, but composition is still conservative. I had this experience of being between two worlds when I studied violin too. I used to play a lot of jazz, improvised also on the street, I had my band. I can’t tell if I like that or playing classically more, but surely I use different “musical energy”. I am not so stitched to the classical side now and it shows in my one of the last compositions. I’ve already used elements of popular music before, combining them with experimental and classical in my piece Seamy Side for bass flute, bass clarinet, piano, cello and electronics It’s fresh and I love how it sounds.«

So can we say that there is one Katarina Gryvul – composer, and another Katarina Gryvul – sound artist?

»It’s the same person! I can tell because I feel like these two are merged into one at this point. Although they started off from completely different directions, then came closer and closer. The contemporary music part takes from the electronic and vice versa. In the end, something in between turns out. I’m curious about it myself! It’s the call of my life, to create something I’ve never heard before. Even if it may sound a bit cheesy [laughs]. Since I was composing as a child (I’ve been taking theoretical and composing classes since I was 6), I’ve always tried to create a timber like never before. It’s also important for me to take inspiration from everywhere. To the point I can’t even tell there’s bad music, I love it all! I can find something good in every style, transpose it and use it in my composition. It can be form, harmony, timber, energy… Yet it’s hard for me to find a piece of music that I like from the beginning to the end. Even in my music!«

I was just about to ask for your inspirations. When it comes to your electronic project I think I can guess some names: Arca, Björk…

»And I don’t listen to them actually! [laughs] But that’s because I don’t listen to music to get inspired really. If I do, I already have something in my head. I’ve also worked in the gaming industry for some years where I always got references on how to do my job. Plus the game industry taught me a lot – you have to work with different styles there. I feel inspiration from there, it makes you open-minded.«

Could you please elaborate on that?

»I worked for Nintendo in cooperation with my friend Svyatoslav Petrov – a composer and sound artist too. I composed and he produced. It was a really hard job, each day a new track in a different style. The work mindset of the Japanese game industry was difficult for us too. They require much less 'easy-music' compared to Europe: lots of modulation, motive techniques, writing for a whole orchestra, very detailed. But it helped me to develop as a composer really fast.«

Besides the game industry related inspirations, could you give some other examples?

»In my solo work the only thing that actually inspired me was a soundtrack for the British series Utopia by Cristobal Tapia de Veer. I remember watching it in 2014 when my main field was still violin. And still being a violinist I’ve heard that music and thought that it is very fresh. I can’t explain. And when I started making my second album Tusha (2022) I realised that all of it comes from that exact inspiration. Actually I realised it even later, while listening to it! The point is, no one knew about that. And then on Soundcloud someone compared the second track of my album to that soundtrack! I was shocked. So that is the only reference I could give.«

And as for the contemporary pieces?

»Honestly it’s the same situation – I never like everything about a piece. When I compose everything starts from the timbre, then I think of other elements of the piece: how will I use them, how will the structure look like. But everything is about timbre. I think about what kind of palette and atmosphere I want. Then what kind of techniques and instruments. Another thing though is my mother tongue. Before the war I wanted to make all my albums in Ukrainian – I love how my language sounds, I need to use it. I come from Lviv, where we speak only Ukrainian. Growing up I didn’t understand Russian at all. Even Polish was easier for me. Tysha has all the lyrics and track titles in Ukrainian, although transcribed to the Latin alphabet, so everybody could read them. In my classical pieces I also like to use my language but as a sound material, for example for rhythmic patterns.«

»Playing as the fourth violin in the middle of an orchestra doesn’t make you feel having an impact. I felt like I was in a factory«

Is there really no genre or composer that inspires you directly?

»As for now my favourite composer is Alexander Schubert, I love what he’s doing. I think that my style of composing is so old fashioned compared to him [laughs]. Only now I write not only for the instruments but also for the electronics – still not enough for me though.«

All the noisy sounds

You also worked with composers close to him stylistically: Stefan Prins and Matthias Kranebitter, right? This intrigued me, because as you said, your compositions are not that electronic. And those are all very »digital« composers.

»Yes, they both pushed me more into electronics during our masterclasses. When I met Prins in 2017 I had only one piece for electronics, then got inspired to do more. In Ukraine we haven’t got a special department for electronic composition, only some electronic and electroacoustic classes. It was new for me here in Austria and earlier in Poland.«

And normally you rather compose chamber music, right?

»Of course, I don’t like orchestra. It’s too big and epic. I prefer to focus on the timber of each musician, plus there are not many orchestras for contemporary music. Also I know the mindset of an orchestra player – I played in them a lot as a violinist. Being a musician also made me love chamber music: you are a bit of a soloist then. Playing as the fourth violin in the middle of an orchestra doesn’t make you feel having an impact. I felt like I was in a factory.«

Do you have an experience of playing in a contemporary ensemble too?

»Not that much. In our Lviv Music Academy we didn’t have any contemporary classes. They didn’t let me play Berg’s Violin concert! [laughs]. At least I could play Bartók a lot, and I loved that.

There are not many pieces of yours for violin, though. Nor for vocals, nor for electronics… All that you use in your solo project so much.

»I got bored with the violin to be honest. It’s the timber I knew all my life, that’s why I avoid it – there are so many other instruments yet to get to know. I really love cello and double-bass. They have bigger 'bodies', all the noisy sounds are much richer. I also prefer lower pitches and if someone offers me a flute I will always ask for bass-flute. Finally I like not commonly used instruments waterphone, sarrusophone, contraflute, wagnertuba. But it’s with the electronics that I can do exactly what I want.«

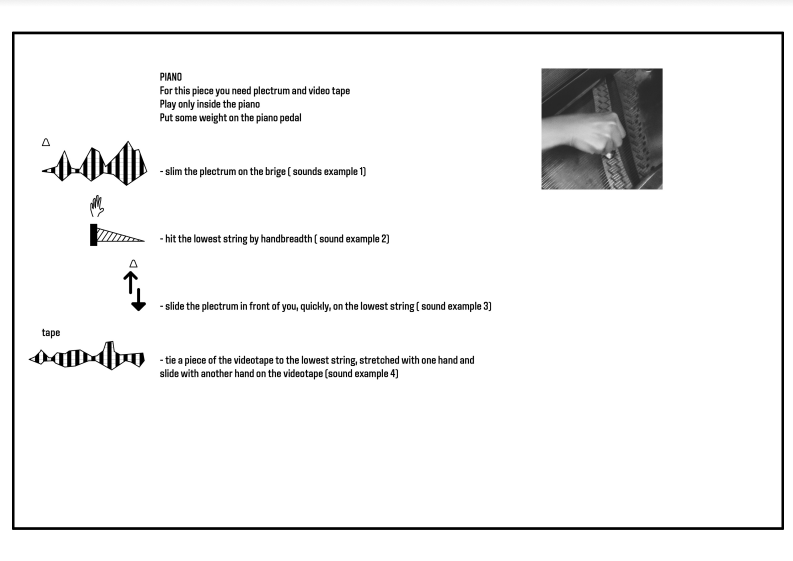

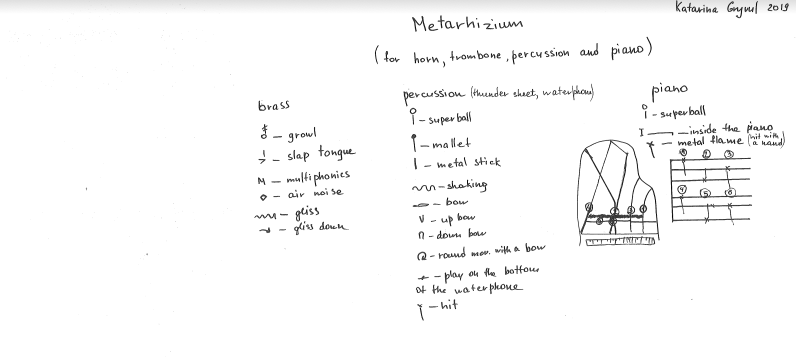

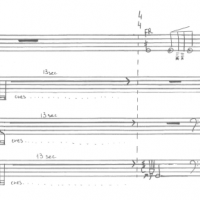

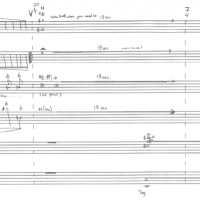

Exactly! Your scores are extremely specific, almost like you tried to synthesise the sound: detailed notation, graphic one too. You attach lots of instructions for your performers including photos of how to play an instrument to achieve a certain sound…

»… they are even given audio samples of the examples! I don’t really work on a piece with performers, but rather present them my finished vision. Yet I like to work with musicians on a personal level. Being a violinist made me understand them better, how to enjoy performing a composition. I don’t want any suffering.«

Yet the scores themselves are very… clear.

»Yes, because I prefer the musicians to focus on the timber. And structure! These are the most important parts for me. You can find clear structures both in my contemporary works and songs, 'my pop projects' as I say [laughs]. If I don’t hear a structure I feel like the composer didn’t work.«

»Back then I already worked with music for games, but still was afraid if I was good enough«

»I prefer working alone«

Most of the scores you’ve sent me are hand-written too.

»I prefer them like this, although I feel insecure about them – if they would be readable for others. Sometimes even I can’t read them at first! But during the masterclasses I’ve always been instructed to use dedicated programs and now I actually do this. Still it’s not intuitive for me to make a contemporary score in Finale or Sibelius. For one score I even used Photoshop and Archicad – it was easier to create a score in a program for architects for me« [laughs].

As a solo artist all of this is not a problem!

»Honestly I prefer working alone. Even in the electronic field I don’t collaborate. I want to feel all responsibility for my work, to count on myself. Although I like writing for “live musicians”. It is a strange world, you need to be straightforward, even fight for your vision. And I like to come up to the musicians during rehearsals, touch the instrument with them. Before providing a score I try every sound myself. I want everything to work as I want.«

Yet on »Tysha« you invited two artists: Flora Yin Wong and Maoupa Mazzocchetti.

»But these were only remixes of my songs. I like their music, that’s why I invited them for the project – not a collaboration though. I am happy that they agreed, I’m not that famous… [sic!] I like that my original music is still felt in their tracks. I did a remix too once, but it turned out more like a rework eventually. Now Tysha opens and ends with the title track – original and remixed. I like how it gives a sense of evolution throughout the album.«

Your electronic career also started off with a collaboration, in a sense. Wasn’t it an album for Kraków label Nawia, a split record with bakblivv aka Ernest Borowski?

»This story started so randomly… I followed the label on Instagram thinking it’s run by my friend). Then they contacted me saying they’ve heard my contemporary pieces and proposed to record a 20 minutes long track. Back then I already worked with music for games, but still was afraid if I was good enough. But I agreed. The label wanted to publish a record that would show the music of artists living in Krakow at that time. And I studied there then, with Marek Chołoniewski as a part of Erasmus. So I got a deadline, sent the material and it got published on a cassette.«

What’s the rest of the story?

»The release party was actually my first live performance. Then I got a proposal to play at Nadmiar Festival, Soundrive Festival, to collaborate with the Pussymantra collective, and record a song for Radio Kapitał… That one turned out eventually to be Finger Tioscock and Bull – the first piece where I sing. I recorded myself with my Zoom6 recorder, sitting in the kitchen. Then I started to make tracks for fun. When I got 7-8 of them, I released my debut, self-published album Inside the Creatures. It was out on the 1st of January plus I didn’t promote it so much… But I wrote to the Ukrainian music magazine Katacult and although they didn’t reply to me at first, they eventually posted it. And that’s all – In Ukraine I only had one concert. It was that presentation of my album Tysha I told about earlier. It’s Poland where I mostly performed. But in the end yes, my career started thanks to Nawia Records, I needed this push. Later the Standard Devotion label gave me a proposition to record for them. But I was given complete freedom, and this is most important for me – freedom in art. If in the future somebody will tell me how to make my music then… [shakes head]. I won’t do this! I love freedom and I know why. But we Ukrainians all have this thing.«

»I also like to listen to the sounds of nature, I fall asleep to this. I love ASMR«

The sound of freedom

How does this freedom sound in your music? I thought maybe of a voice – the most personal instrument. Yet on your albums the voice is very distorted.

»For me freedom is not about voice or instrument. It’s about ways of thinking. Freedom of personal choice without condemnation of society.«

Do you feel more freedom in the electronic scene?

»Actually yes. There are more open people and more people listening to it in general. In classical music everybody has a mask. Like everyone in the society, but this is a different feeling. You are also constantly asked for your philosophical background and aesthetics… In electronics people don’t really care, but they listen to it. More fun I guess. I listen to the most basic music too. Normally I overanalise what I am listening to, the music has too much information for me. That’s why I also like to listen to the sounds of nature, I fall asleep to this. I love ASMR. I’ve been following this concept for 10 years now – I remember it still being a niche and the creators using really bad microphones and video quality. But it affected my second album too. You can hear it in all those [gasps] that I haven’t edited because I wanted the sense of intimacy.«

So soundscape is important for you too. By the way, your soundscape now is so beautiful!

»I live in a really nice place – an old building with a garden. The birds start to sing at 4 a.m. I also live close to the opera house, I’m lucky. And I had some projects with field recordings. One for my Gaude Polonia stipend program – field recordings of Cracow, chamber orchestra (made of my friends), video and electronics. It was actually a project dedicated to the war in Ukraine, from the time it concerned the Donetsk region. In the project I used video of post-war Warsaw and combined it with the sound of modern Cracow. By the way, after the war of this year started I realised how many pieces about war I actually have written. It must have been subconscious, always in the background.«

And the other project, the RIVERSSOUND?

»It also took place in Cracow, I was recording Vistula river. I love this project so much. I explored many spots in the city and discovered that this river doesn’t have a sound in that city. In summer, the water in the Vistula flows very slowly and it is almost inaudible, the dams are open only slightly. Also, all this is probably due to the fact that there are no large slopes, and the flat surface prevails and for the most part in the centre of Krakow, Vistula is surrounded by walls.. I wanted to catch water, but always got the people on the recording. Even far from the city, I wanted to work with the sound of the water itself.«

And what does your hometown Lviv sound like?

»There’s no river unfortunately. The centre is very noisy, but not because of the cars (they are prohibited there), but because of the people. For me Lviv is talking of the people and some street music. Actually I was one of the first people from the younger generations playing like this there! The Music Academy wasn’t very fond of it though« [laughs].

In the interview with Seismograf you said that Lviv and Graz are similar. Are their soundscapes too?

»Completely not. Here at 10 p.m. everyone is asleep, no cars, no people, empty. In Ukraine something is happening until late at night. But it’s good to study here. My University is well equipped, I have all the technology for the ambisonics for example. And this is what interests me now the most – music in space, how it’s moving.«

So how are you feeling studying there at this famous University of Music and Performing Arts Graz, at the Computer Music and Sound Art faculty that seems perfect for you?

»It’s very good indeed. I am not being pushed by my teachers, the tempo of studying lets you develop. The subjects are about your opinion and point of view. We always have discussions and the teachers are very open. It’s not so hierarchical like in Ukraine. Here I feel equal, teachers are more like mentors. But they make you feel at the same level. And they follow your ideas. In Poland I also got that feeling sometimes. It was already better than in Ukraine, but still I didn’t feel equal.«

»I’ve always wanted to be the teacher that I wish I had«

»What’s interesting though, I didn’t plan on going to Graz, it was spontaneous. I handed in my application, forgot about it and 3 months later got accepted. In my life I went through a lot of exams (for violin, composition), but this time it was rather a conversation on my vision in music and art, based on a portfolio. It took place on-line, but I rather thought I’ll pass it next year. I even asked about the possibility of having on-line classes in Graz because back then it was impossible for me to move out from Cracow – many documents and legal procedures as I said. But I was accepted, and because I hadn’t expected it, I collected all the papers and everything in a big rush.«

Finally you’ve become a teacher yourself. Can you please tell us more about the Gryvul School project?

»I think I love teaching even more than composing. I’ve always wanted to be the teacher that I wish I had. For me, launching the school aimed to make people believe that they can make music, believe in themselves – because most of my teachers didn’t make me feel it myself. I don’t want to be the person who decides if someone can be a musician or not. If someone feels the desire for music, who can tell them not to do it? The most important aspect of teaching for me is to find a key to develop a person. It’s an amazing process for me, also the psychological, motivational side of it. I don’t believe in talent at all, I believe in hard work.«

So how does one work in the Gryvul School?

»It’s on-line and you can choose to work in a group or individually with me – then you tell me what you want to achieve and I prepare a special program for the course, depending on your goals. In a group where the levels and backgrounds differ I usually give different homework to each student. For now it has worked as a project only for Ukrainians but I am about to launch an English website and open the courses internationally. I already had a request from a girl in Poland. Usually I run two courses (three months each) during a year. I don’t want to make it too commercial though.«

»Music is the thing that makes me most happy, so I want to show this world to others. Including both feeling and knowledge. And talking about it, teaching it makes me realise how I love it even more and makes me even more happy!«

The interview took place on-line on the 1st of June 2022 and was first published in the Polish magazine Glissando.

The interview has been authorised by Katarina Gryvul.

The interview was first published thanks to the aid of European Cultural Foundation.