Anything Can Become Music – Even a Bunch Of Fake Frogs

The 43rd edition of Musica unfolded over two full weeks (September 19 – October 5), wrapped in Strasbourg’s orange-brown autumn colors. On Friday evening during the festival’s middle weekend, I sat down in the Le Maillon theatre and immediately felt alarmingly out of place. I was there for a talk with artist Joris Lacoste before the performance of his work Nexus de l’adoration (2025), but Lacoste spoke in French for 45 minutes, and I strained to catch a sentence here and there.

Just as I was about to flee, the theatre filled up with people

Not a single word of German to cling to. Just as I was about to flee, the theatre filled up with people. A remarkable crowd of both young folks in baggy jeans and older ones in colorful glasses and silk scarves. The café’s sliding doors opened, and guests bought wine and hot meals, pushed tables together, and chatted softly while the artist spoke. It turned out to be anything but exclusive.

We moved comfortably into the auditorium, where Nexus de l’adoration was performed by a group of very diverse performers. A playful tribute to difference and randomness, staged as a strange multimodal non-genre between music theatre, moving bodies, monologues, electronic soundscapes, drum solos, and suddenly emerging choral sections. All the performers were on stage non-stop, recalling an impressive number of movements, sequences, and words. It lasted two and a half hours without intermission, and I imagine it was tremendous fun – if you understood what they were saying.

A European festival in French

Festival director Stéphane Roth emphasized that Musica is, above all, an international and inclusive festival that brings new music to the people. The middle weekend, for example, was shaped by a Canadian collaboration with Montreal’s MUTEK Festival and included one Danish composer, Knud Viktor (1924–2013), on the program, while a Polish collaboration had filled the opening weekend. According to Roth, there are even plans for a larger collaboration with Danish artists in the coming years, and curator Anna Berit Asp Christensen’s name came up several times.

Of course, every educated person should master French. Should!

Yet, in the following days, I realized that nearly all printed programs, verbal instructions, and performances with spoken elements were in French. Of course, every educated person should master French. Should! But in practice – and especially in our increasingly anglified or even Americanized linguistic culture – that element didn’t feel particularly inclusive. Strasbourg lies at the heart of Europe and, as an EU capital situated in a bilingual borderland between French and German, has all the prerequisites to become a melting pot for new international composition music from across Europe (and the world). Despite the language barrier, the festival fortunately also offered plenty of play, community, and delight.

An epidemic of playfulness

The performance Beautiful Trouble (2024) by American Natacha Diels and the JACK Quartet was a surreal hybrid of string quartet, choreography, and digital visuals. Most of it was in English, with French subtitles on screen. Could one imagine the reverse at the other performances?

The four JACKs iconized themselves on screen through Comic Sans-like animations and AI-generated (though poetic) Adobe Stock imagery

In the program, Beautiful Trouble was described as a dramaturgically staged TV series between chamber music and music theatre, but it was far stranger than that. The four JACKs iconized themselves on screen through Comic Sans-like animations and AI-generated (though poetic) Adobe Stock imagery.

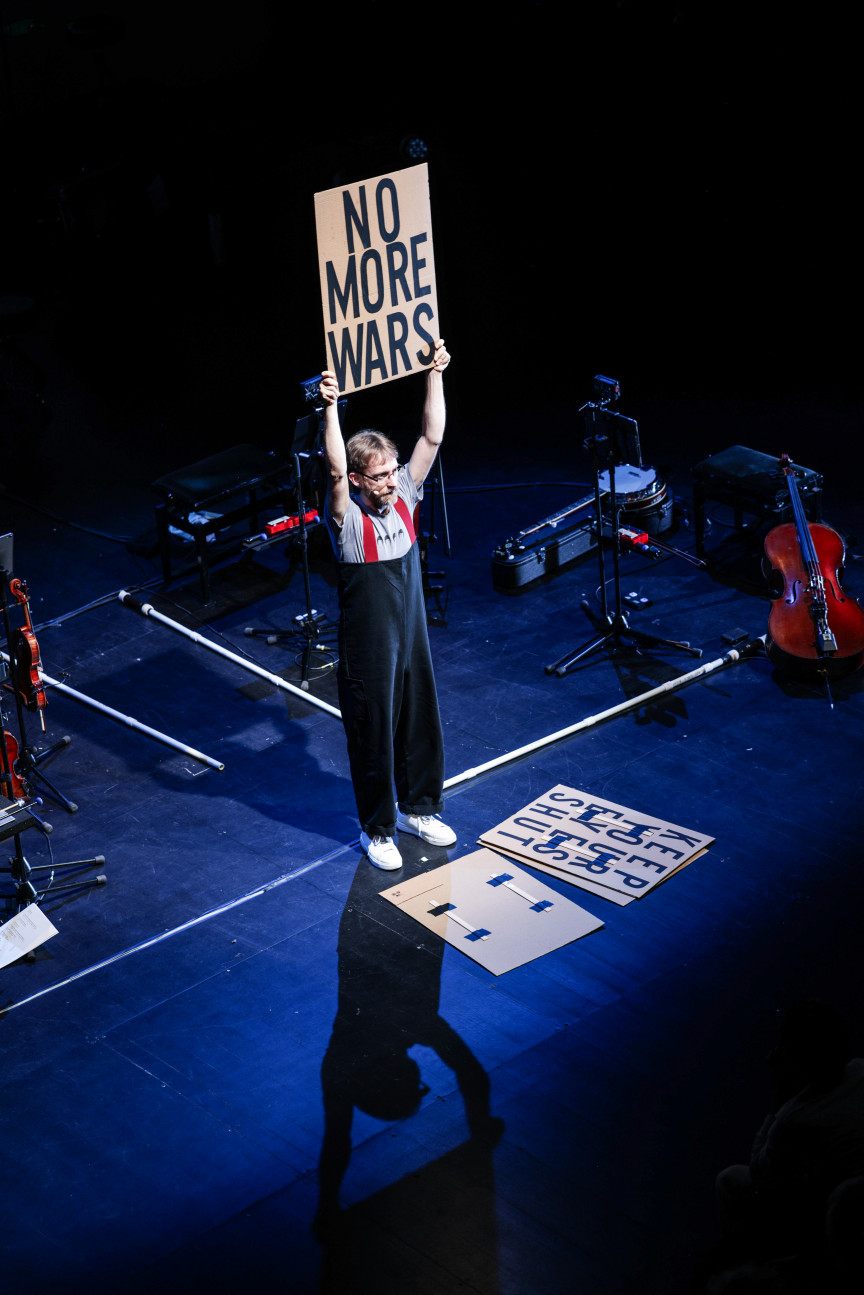

On the physical stage, the four grown men wore overalls, and both the tactile materiality of their bodies and strings were juxtaposed with digitally mediated reality. The choreography and composition demanded near-superhuman coordination that never faltered – making it all the more vulnerable. At moments, melodies trembled just below the sound surface like an overpainted symphony. It was pure liberation from convention. I couldn’t help but wish for a glimpse into the compositional process or score – it seemed impossible to invent at a desk or to find anyone to perform it who hadn’t been part of the playground from the start.

When everything can become music – even for children

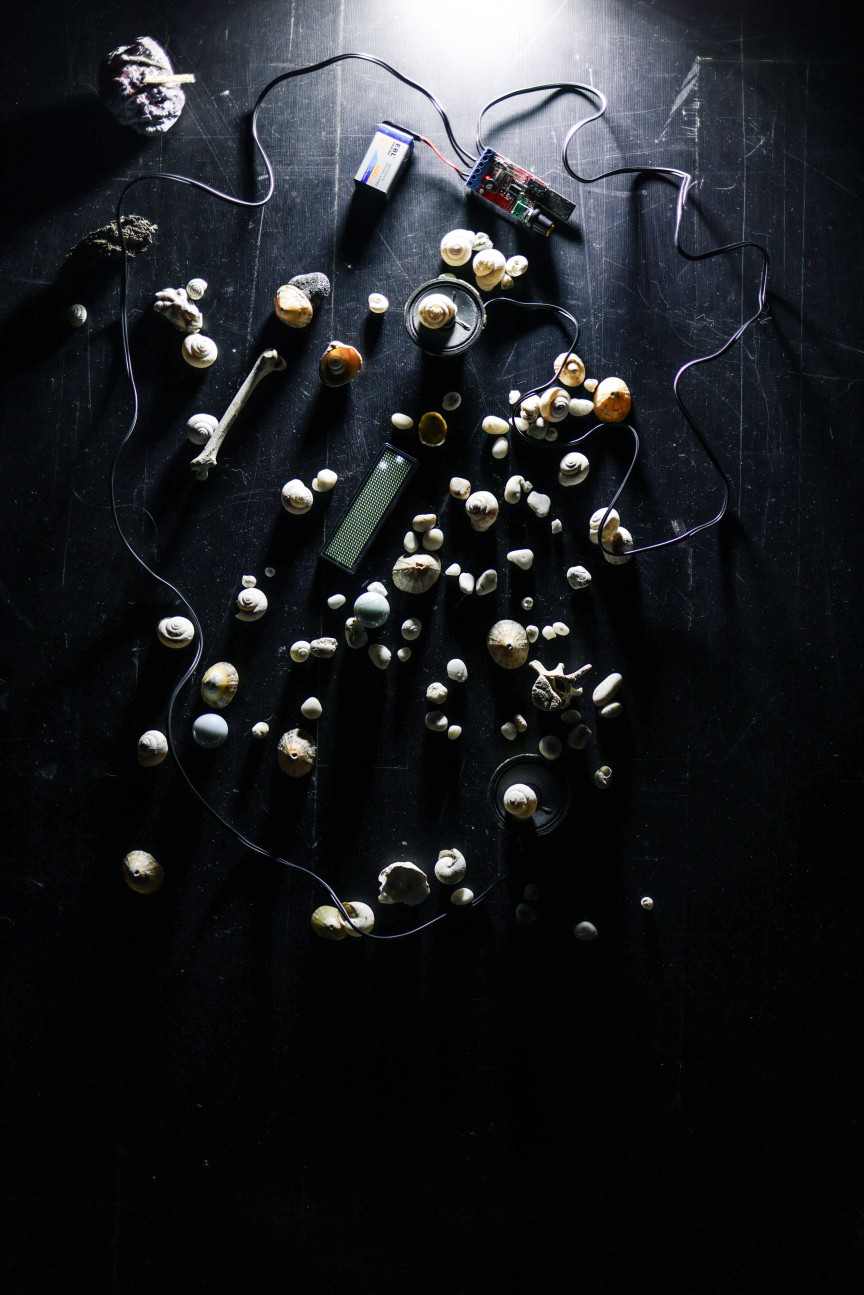

The following morning, at a children’s concert by the percussion group Sixtrum during the parallel Mini Musica festival, I had the odd feeling that it wasn’t all that different. Like Beautiful Trouble, it featured overalls, tightly choreographed movement, and a fascination with tactile sounds and playful instruments. The feeling continued in Murmure (2025) by Stéphane Clor and Kapitolina TsvetKova – a cabinet of curiosities filled with mechanical creatures between animal, technology, and nature that moved or emitted smoke (and smells).

Fortunately, one brave soul in our group dared to wind up the keys on the backs of a group of fake frogs

The youngest audience members might have enjoyed it even more had it been made clear they were actually allowed to touch things. Fortunately, one brave soul in our group dared to wind up the keys on the backs of a group of fake frogs, which then clattered across the floor in chaos.

And where was the music in that? Well, the sounds of things – and people – became, with a bit of goodwill, a collective composition as Clor wandered around tweaking and adjusting, constantly changing the sonic landscape.

These works crystallize a core idea of the festival: that humans are fundamentally musical, and that this must be discovered through play. Since 2020, Musica’s strong focus on concerts for children has underscored the need for more serious composition for young audiences – because when combined with pedagogical intent, it might be both the most fun and the most complex thing one can do. At least, that’s what the director believes. In March 2026, Mini Musica will become a festival in its own right, occupying a niche in the music world. To meet demand, the audience capacity will rise from 1,500 to 4–5,000. Until now held at the city’s Centre chorégraphique de Strasbourg, the festival will next year expand to use the entire city, just like the adult Musica. One to watch.

Musica, in fact, uses the entire city as its stage. As a visitor, it was a brilliant way to explore Strasbourg

Several festivals in one

Musica, in fact, uses the entire city as its stage. As a visitor, it was a brilliant way to explore Strasbourg: we saw nearly all its churches from the inside (except the grand cathedral). Each venue was packed, with most concerts completely sold out. That might be due to the festival’s local character – bringing the music to the people. It was clear that Musica functions both as a stage for experimental composition and as an open invitation for a broad audience to experience that music in relaxed, familiar surroundings. And it’s not only Mini Musica that operates as a festival within the festival.

The Strasbourg venues also served to highlight international connections – notably with Canadian artists from Quebec and Montreal. Their MUTEK festival curated the late-night program on both Friday and Saturday in Église Saint-Paul, packed with seated and reclining listeners.

Particularly striking was Kara-Lis Coverdale’s stormy organ concert, where violet light flooded the church as she, facing the great instrument (and with her back to the audience, of course), swung her long hair in time with dark, elongated experimental tones.

This MUTEK takeover showcased new Canadian music in an original way, though it did become somewhat drawn out. The more musically rewarding experience came in daylight with Montreal’s Quatuor Bozzini, performing a one-hour potpourri of works by Canadian composers Nicole Lizée, Cassandra Miller, Tanya Tagaq, and Claude Vivier. Especially Tagaq’s Sivunittinni (2015) burst with energy – something I realized I’d been missing all weekend.

The Samsø-born sound artist and self-proclaimed »sound painter« spent most of his adult life with a microphone buried deep in the landscapes of southern France

Only Knud is dead

Naturally, I was especially curious about the performances of Danish artist Knud Viktor. The Samsø-born sound artist and self-proclaimed »sound painter« spent most of his adult life with a microphone buried deep in the landscapes of southern France – making him perhaps as French as Danish. Pascal Normandin curated Viktor’s electroacoustic works in a meditative setting with immersive surround sound, sleep masks, and floor cushions for the audience. But it was hard to know how to listen to creaking trees and other processed natural sounds for an hour. Fortunately, the organizers explained the concept afterwards – in French, of course.

Even so, it was an example of works that live beyond the artist himself. Both Viktor performances were fully booked and seemed to function just as well now as when he was alive.

In fact, Viktor was one of the few composers on the weekend’s program who is no longer living (alongside his near-namesake Claude Vivier, 1948–1983), and a persistent question followed me from one musical playground to another: How can these works be preserved and restaged? Could Nexus de l’adoration be performed with a different, equally diverse cast? Could Beautiful Trouble exist without JACK Quartet? Could all the little gadgets from Murmure be meaningfully stored in shoeboxes and restaged across the world 50 years from now? In short: are these works written only for this moment – or also for the future?

A harmonic breather from the digital rush

JACK Quartet’s second concert put my doubts to rest. Their tribute to American composer John Luther Adams, featuring The Wind in High Places (2010) and Lines Made by Walking (2019), closed the weekend’s program. These works emphasized the link between bodily exploration in music, the festival’s abundance of string quartets, and the occasionally flat dynamics.

Whether one likes it or not, linguistic paratexts shape musical experience

Yet it was a harmonious respite from the electronic and visual – just four strings on stage that somehow sounded like everything else: bells, accordion, horns, flutes, wind in high places, deep rivers, long steps. These organic landscapes were aptly guided by the works’ titles. Whether one likes it or not, linguistic paratexts shape musical experience – so it’s nice when one can understand them. It makes an otherwise successful international festival feel just a bit more international.

Musica, Strasbourg, September 19 – October 5

English translation: Andreo Michaelo Mielczarek. Proofreading: Seb Doubinsky