See Venice and Throw Up

»Habit is the ballast that chains the dog to its own vomit.«

No, this is not a quote by Marie Koldkjær Højlund. She does know its author, Samuel Beckett, who in 1930 published an essay on Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, pointing to the power of habit to trap people in uncomfortable patterns.

»I’ve always been out of place – whether as the girl in the boys’ band Nephew, or now as the researcher who also writes pop music«

Højlund is an associate professor of sound studies and thus has a broad academic frame of reference. Still, she does not know this particular quote when I (naturally, a little way into our conversation) cautiously introduce it at the small café on Jægergårdsgade in Aarhus, which – like many other mornings – forms the setting for Højlund’s itinerant working life.

Her energetic charisma and genuine curiosity propel the conversation at full speed toward the idea that habits and vomit are precisely what she seeks to stage in both her academic and artistic work as a sound artist, musician, and composer. Don’t worry – a clarification will follow. But first we have to trace her path along a multifaceted career trajectory.

We live in a world where you’re supposed to choose one path

»Back when I thought I had to choose between music and research, of course many people cheered on the familiar narrative of ‘following the music and listening to your heart.’ It was a real life dilemma, rooted in that damned idea that we live in a world where you have to choose one path – and be completely unique. Especially in music, we keep reproducing a cult of genius that should be obsolete. But the writer Merete Pryds Helle pointed out to me that there are fewer women in research than in pop music. That became decisive for me. Sometimes there’s enormous power in a single sentence someone says.«

»I’ve always seen music as my core,« she explains – quite literally a product of a home with a piano. From the age of six, Marie Højlund took piano lessons, and in the family choir she early discovered the resonance of musical community, singing Handel’s Messiah at the age of twelve. But she didn’t enjoy practicing the piano. Instead, she tested the instrument’s limits with new compositions – singing into it, for example.

Although she continued with guitar and bass, the computer became her primary tool around the year 2000, and pop music filled the 2000s through her bands Tiger Tunes and Marybell Katastrophy.

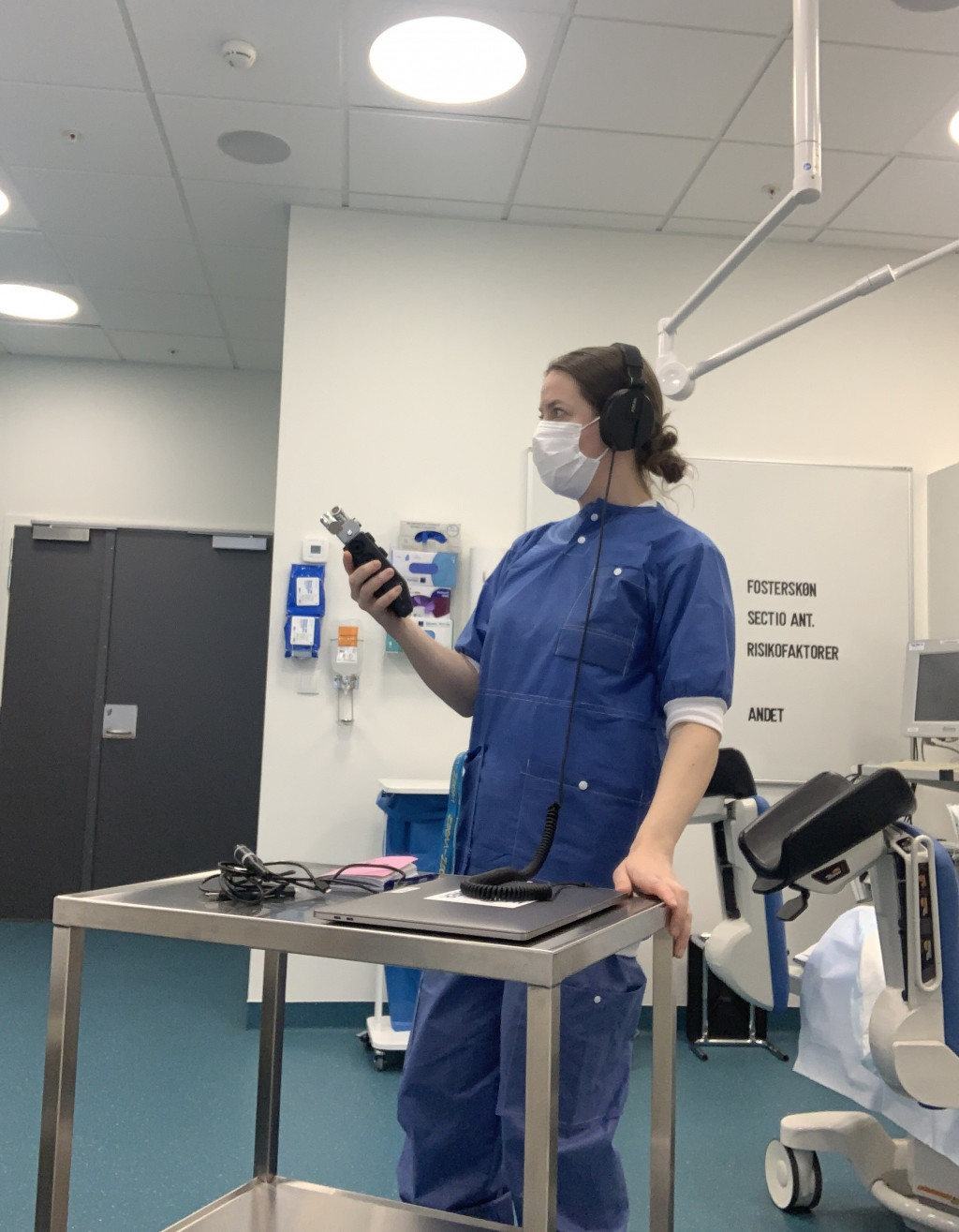

In 2012 she began her PhD project, designing a sound furniture piece for hospitals, thereby integrating her artistic practice deeply into her research from the outset – what is known as practice-based research.

Højlund’s practice thus unfolds not only in her office at Aarhus University, but also in rehearsal rooms around the city and in her home studio and music room. I ask whether she is often asked when she is an artist and when she is a researcher – and whether that isn’t an unnecessary division.

»People always think I’m making a gadget. And I’ve made plenty of gadgets – they’re often part of the output«

»Yes. That’s the question I get most often, and it’s absurd. There is no division in my life or practice. Those kinds of categories are constraining. I’m very inspired by the scholar and writer Sara Ahmed, who talks about a duality of hypervisibility and invisibility in the body that is ‘out of place.’ I’ve always been out of place – whether as the girl in the boys’ band Nephew, or now as the researcher who also writes pop music. You’re not on equal footing; you’re simultaneously overlooked and yet stand out.«

I can’t help interjecting that just as the division between research and art can be a limiting categorization, there are also constraints embedded in the very concept of practice-based research. As a colleague once pointed out: what would its opposite be – impractical research?

And then we laugh a bit.

»Just as I don’t separate art and research, I’ve never separated art and everyday life«

Gadgets, (habit) ruptures, and interventions

»For me, practice-based research is very much about intervening in something and being creative. People always think I’m making a gadget. And I’ve made plenty of gadgets – they’re often part of the output. But fundamentally it’s about asking questions and gaining knowledge through processes. A good question might be: how can delivery rooms become nicer places to be? I’ve tried to explore that through art as process. It’s a huge privilege to have a practice that allows you to understand theoretical concepts through doing.«

»My works rarely end up in museums. They’re guided by encounters with realities, environments, and cultures«

»Just as I don’t separate art and research, I’ve never separated art and everyday life. Something that became defining for me were the everyday encounters in the work LYS – landskab og stemmer (LIGHT – landscape and voices) (2011), where artist Elle-Mie Ejdrup Hansen and I drove around six municipalities with a caravan equipped with recording gear, inviting people in from the street, workplaces, and schools to read Inger Christensen’s poem »Light«. The recordings from the caravan became a sound work played in various locations in the East Jutland landscape.

»We are creatures of habit. We often think on a very grand scale about what we need to do differently in a fairly fucked-up world«

The audience arrived at dusk and wandered through the work with their picnic baskets. My works rarely end up in museums. They’re guided by encounters with realities, environments, and cultures, and they break with expectations of the contexts in which we usually encounter art. How often do you bring a picnic basket to an art exhibition? I love those collisions and breaks with our habits – and I think there’s huge potential there.«

»Too much art is about losing your footing. I want to offer the audience a safe place«

This is also evident in one of Højlund’s newest works, Svanesang (Swan Song), created with Julian Toldam Juhlin and Christian Albrechtsen, which records boys’ voices in transition from the Herning Church Boys’ Choir. It’s a very concrete focus on physical rupture. But what is the potential in that?

»We are creatures of habit. We often think on a very grand scale about what we need to do differently in a fairly fucked-up world. I ask what the role of art is. Through practice, you can break habitual perceptions and categories – and I’ve gradually realized how easy it actually is to break habits if you’re invited to do so, and how hard it is within established frameworks. To paraphrase philosopher Timothy Morton, you only really see things when a rupture occurs – like when you travel to another country and everything suddenly comes to the foreground. But I don’t want to go so far that no one understands it. Too much art is about losing your footing. I want to offer the audience a safe place from which to explore everyday life.«

»I can’t give stars to Death in Venice at Teater Republique because I don’t understand it«

This tempts me to bring up Morten Buckhøj’s recent review of the stage adaptation Death in Venice at Teater Republique. Højlund composed the music for this staging of Thomas Mann’s famous novel (yes, we’re back in the world of literature), about an older man’s longing for youth and confrontation with his own mortality. Reviewer Buckhøj had to concede defeat because he did not understand the performance.

»I love that review!« Højlund exclaims. »I’m fascinated by something that can’t be evaluated because it can’t be categorized. When a canonized novel is staged as a performance work, a kind of categorical confusion arises – perhaps also tied to our attention economy. We live in a world full of signals, and Death in Venice is a work where the background becomes foreground: quite literally, the water rises – the city’s background – and takes over the narrative. So this rupture of categorization is embedded in the literary source itself.«

»Directors are pretty damn brave. They’re not people-pleasers; they work with attention«

»That’s why I love making theatre. It’s a laboratory for life, where you can break habits. Directors are pretty damn brave. They’re not people-pleasers; they work with attention. In Death in Venice we dared to draw scenes out until they became downright painful: there was an overly long scene with an old men’s band farting and indulging in crude humor. Theatre dares to stay with the embarrassing. Do you feel disgust at becoming old? Yes. Do you leave the theatre thinking it was pleasant to watch? No. But a survey shows that 0% of us want to end up in a nursing home. Theatre says: this is something we have to confront, look at, and feel disgust toward. And fortunately the work doesn’t end with disgust.«

Habits, death, and vomit

And here we are back at habit as ballast, chaining the dog to its own vomit. Højlund immediately connects the quote to what philosopher Julia Kristeva has called »the abject«: the disgust toward something that was once part of the body and the subject but is expelled as object – vomit, blood, feces, clipped toenails.

»There’s a disgust toward things that are expelled from us and from our culture. In the abject, we’re confronted with something of ourselves that is dead, and in that we see our own mortality. That’s exactly what Death in Venice is about. But on a broader societal level, we see it, for example, in homelessness – people expelled from our society. I’ve worked with homelessness as a theme and used art to break some of the habits that bind us to that disgust. Through art, you can be forced to look at it and say: this is part of you and your everyday life.«

In this way, Marie Højlund constantly returns to everyday life as a tool for engaging with major crises.

»As music philosopher Robin James argues, there is resistance in apathy and melancholy – in not overcoming, but staying with the difficult, looking at the vomit, foregrounding the abject. I feel my art is a practice of resistance to the large, incomprehensible crises Timothy Morton calls ‘hyperobjects.’ My resistance lies precisely in staying local and non-spectacular.«

»I don’t sit around waiting for inspiration – that doesn’t work«

Trust chance – and sleep

Finally, I have to ask the most banal yet pressing question of all: how on earth does Marie Højlund manage all of this?

Her answer is refreshingly everyday:

»First of all, I’m good at sleeping. And taking time off. It’s important to acknowledge everything that surrounds art – what Cecilie Ullerup Schmidt calls ‘production aesthetics.’ It also helps that I almost always work with others. And then I’ll say this… well… I’ll just say it: I have an extremely easy time making music when I need to. I don’t sit around waiting for inspiration – that doesn’t work. I work a lot with chance, because I think randomness has to do with rhythms and connections that can’t be planned, but that I trust.«

And what are the plans for 2026? Simply to enter the gaming industry, a field Højlund has yet to conquer.

She is currently composing the music for the video game Out of Words, sold to Epic Games. The trailer has already been shown to 150 million viewers at the gaming industry’s equivalent of the Oscars. The game is a stop-motion story about two dolls who lose their mouths and fall into a world where they must rediscover language.

»One thing I don’t have time for, though, is making my own album in the solo project KH Marie«

»It’s handmade and about love, processes, and voices in a constructive story. It’s exactly the counter-movement we need to today’s AI productions,” Højlund emphasizes, before mentioning other upcoming projects, including an adaptation of the novel Barbara at Aarhus Theatre.

»One thing I don’t have time for, though, is making my own album in the solo project KH Marie after the debut in the pandemic year 2020. I have lots of songs – it’s pure desire – but precisely for that reason, I’m waiting until there’s time instead of forcing it through.«

English translation: Andreo Michaelo Mielczarek