Across America – a Grown-up Boyband’s Search for a Sound

Prologue – Warsaw, September 2025

»We only rehearse on farms and in hotels,« says Eivind Buene as he lands in Warsaw. As usual for this band – Tværs – Kullberg’s hotel room is transformed into a rehearsal space, this time with a view of the Palace of Culture in the Polish capital. And after the concert at Opera Warszawska, 400 Polish audience members drift singing into the night – the melody was written on a dusty roadside somewhere in Louisiana.

They hardly know each other yet. The investigation has only just begun: What can they actually do together?

Tværs began as an idea dreamed up by cellist Jakob Kullberg. Two years earlier, he had persuaded composers Niels Rønsholdt and Eivind Buene, guitarist Jakob Bangsø, and the Copenhagen-based Canadian Bradley Axmith to join him on a road trip through the American South to explore a single question: Could they become a band?

Hitting the road to become a band – Spring 2023

No one had told Buene he needed to bring his own guitar. Their first stop in Louisville is therefore a local music store, where he buys an acoustic Fender. Soon after, Tværs rehearse for the first time in a worn-out hotel room where overly salty meals sit wrapped in plastic.

»I dream of the finest tobacco,« sings Rønsholdt. »Elegy is my tonic,« Axmith adds in his deep voice.

The songs have titles like »Kentucky Pleading« and »The Tree« – classical structures mixed with uneven rhythms and improvisation. Bangsø draws a bow across his guitar; Kullberg plays the cello horizontally across his lap. »The music is allowed to fall apart a little,« he says. »If it’s too tight, it becomes kitschy.«

They hardly know each other yet. The investigation has only just begun: What can they actually do together?

»I went looking for a poet in Kentucky and found you«

Rune Mielonen Grassov sits in the corner with his camera. He is filming how – and whether – these five musicians can become a band. In the hotel room, Kullberg describes his solo in »The Work Song« as »a cow that doesn’t know how to give birth.« In this band, he says, you’re allowed all the curls and embellishments you want. It must not be perfect.

Time for local cuisine: fried chicken and hot-water cornbread.

Oh Louisville – it’s basically a boyband

In Louisville, you walk straight into the past. Forty streets of villas in decadent styles. In front of one house, white statues and even a steel dog peeing on a fountain. Peanut butter and jelly shots are a specialty, and »Decadent dining« can be found all over Kentucky’s biggest city, washed down with bourbon. Not a slave whiskey, though it would have been fitting. And it is here, in a crossroads of histories, strong and sweet flavours, that Tværs searches for a sound.

The first concert takes place at the University of Louisville in front of American music students. »The father of the next song is Schubert,« Buene tells them. »He was a kind of singer-songwriter. He invited friends home, sat by the piano and sang.«

»Now my body is burning / You poison me with your tears,« Buene sings. The rest of the band hums along. There isn’t a single trained voice in this band. All five sing with whatever beak they’ve got. They need a local voice mixed in – and they find one.

»We’re here to become a band. I went looking for a poet in Kentucky and found you,« Kullberg says to Maurice Manning, who has joined them for dinner after the concert in a fancy restaurant. Manning writes about a world that is still handmade. He describes his poetry collection The Gone and the Going Away, written as if he were a simple farmer, not a Pulitzer-nominated poet. His language is both earthy and lofty at once; he lives on his family farm in Kentucky and knows his land and his Bible. At the table, he reads »A Prayer for Pigs«, which begins: »O, God my swineherd God, send me two pigs, please.« Tværs has already set the pig poem to music.

The next day Manning writes:

»I’m deeply flattered that you've taken a shine to my poems. And also grateful for our conversations. It's good to meet another artist, working in a different form of art, and realize how much we have in common, both in practice and sensibility. And to acknowledge how much we owe to intuition as the thing that summons us and leads us. It's all bigger than any of us, and we are participants and travelers in a realm given to us. And we try to do something with our gifts that will matter to others. Thank you for bringing us together, for the good company, and to share the spirit. I believe you'll trust what's going on and will have something original and beautiful once you get on the other side.«

They now feel welcome. And when Bangsø happily rolls into the hotel parking lot after devouring monstrous breakfast burgers with his American guitar colleagues during their Louisville stay, spirits are high: »Come on, friends, let’s drive.«

Their first stop is not far away – still in Louisville. A Peruvian BBQ chicken bar. The owner insists on taking photos with the musicians, who are promptly promoted to a band. He also offers to connect them with a Croatian company that makes T-shirts for his black-metal friends.

In Louisville, two of them buy skateboards before heading south

Tværs hasn’t reached the merch stage yet. But they talk about being a collective travelling together, getting »insane amounts of energy from being in the world – it’s like folk high school,« they say. In Louisville, two of them buy skateboards before heading south – with a detour to the world’s largest cave system, Mammoth Cave National Park, warmly recommended by Manning.

Destination South (Route 42)

Kullberg calls Axmith »the foreign element in the band.« He’s not a professional musician; he’s Kullberg’s karate teacher – and a banjo amateur. When he drives the rental car, he ignores the GPS and follows his own route. The band also works without rules: »We need another a cappella rehearsal. Yes, in the car,« Kullberg says. They rehearse wherever they can – hotel rooms, parking garages, and especially the two cars. They constantly invent things on the way. At the truck-stop gas stations, more and more trucking magazines pile up. Singing, they drive into Cincinnati.

»I didn’t grow up with Danish folk songs but with Elvis, Kurt Cobain, and Janis Joplin«

From classical training to Old Tavern (Cincinnati)

At Cincinnati’s College-Conservatory of Music, professor Stephen Ferre wanders the corridors searching for a bass amp for Rønsholdt. After a concert for the students, there’s a Q&A: they want to know more about Tværs.

»Cello is old Europe. Guitar is America – the new instrument,« Rønsholdt says. »‘Heavy is the Heart’, from my album Country, is about identity, cultural identity. I didn’t grow up with Danish folk songs but with Elvis, Kurt Cobain, and Janis Joplin.«

It is actually the first time the musicians talk about their reasons for joining the project.

»I wouldn’t have done this if Jakob hadn’t asked«

Rønsholdt explains the fundamental difference between working alone and working in a collective – both the process and the result are altered.

Buene turns to the students and urges them to find a voice among themselves: a librettist, a poet – maybe their own Maurice Manning. »Everyone has a story to tell – no matter where they live,« says Buene, who is a music professor in Oslo.

»It’s unpredictable, because we’re such different musicians. There’s a meeting between the European Lied tradition and the American singer-songwriter tradition. It’s about the voice and the raw expression – not filigree piano accompaniment. As a composer, you’re usually protected – sitting in the hall. Here, you’re right in the middle of it. But I wouldn’t have done this if Jakob hadn’t asked.«

In the evening, professor Ferre has arranged a concert at Cincinnati Old Tavern. Some locals ask the bartender whether Scandinavians use strict decibel limits since they’re playing so quietly. Old Tavern is known for hard rock. Faculty members are present. Ferre thanks them: »I think it will remain the highlight of my time at CCM. It was so unusual to see my colleagues get so excited.«

»Why am I doing this? What is the point of this band?«

An A in Memphis – what does it mean?

A week into the US trip, the inevitable hits: small irritations, small jabs – what all bands eventually face on the road. On the way to Memphis, doubt creeps in for Kullberg. »Why am I doing this? What is the point of this band?« he thinks, as the dusty landscape drifts past outside the car window.

The band talks about bringing more classical music into the project. They debate the hierarchy between ukulele and guitar. Maybe Kresten Osgood could add some smack to the music. Should Bára Gísladóttir or Ida Duelund join?

There’s an irritating buzzing sound in the Motel 6 room where they rehearse. »It’s an A,« Kullberg says to the others, who are sitting on the beds with their instruments. He has assembled a band where the irritating is part of the concept. A stone in the shoe. It’s that stone they keep turning and worrying on the journey – while insisting that the music must not become too pretty.

Maybe Kresten Osgood could add some smack to the music. Should Bára Gísladóttir or Ida Duelund join?

Kullberg keeps reminding Axmith – the band’s outsider – that he must not practice: »You mustn’t get too good, Bradley. And we need serious texts for you. Not marshmallow texts.« In Memphis, Axmith discovers that his role is not only as a banjo amateur but as a chanting poetry reader with a warm, raspy voice.

Rønsholdt envies Bangsø’s bass voice:

»Jakob, you can sing so deep, and not just in the morning before ten. You have a beautiful voice!« Maybe it’s still the barbecue dry rub lingering from the night before, when they ate at Elvis Presley’s favourite restaurant, Charlie Vergos’ Rendezvous, where the staff persuaded Kullberg to play Bach as they prepared to close. The owner had said: »Can you come back tomorrow at 1 pm and give a concert?«

»In this band, we rehearse the form – and then we just go in and play. It should sound trashy«

»We can’t include all the new stuff today, it’s too risky. And poetry reading won’t work,« says Buene. »We’ll never get it to groove.«

»I get what you mean,« says Kullberg. »But in this band, we rehearse the form – and then we just go in and play. It should sound trashy.«

Rendezvous has a large banquet hall upstairs, and it turns out Tværs is playing at the launch of American bestselling author Frank Greaney’s twelfth book in the Gray Man series. Greaney seems delighted with the Scandinavians’ take on bluegrass.

After Memphis, the landscape grows greener; the air thickens. The heat vibrates everywhere – in power lines, in the buzzing insects, in the horizon itself. This is where Emerson and the Transcendentalists spoke of the American Sublime: the feeling of standing inside something so overwhelming it both lifts and erases you. For Tværs, it is not a religious moment but a sonic one – a place where noise, silence, and heat melt into another kind of recognition.

»Here you need to believe in something to be able to play«

They drive in two cars. In one, Rønsholdt and Buene talk about songs that don’t yet exist, and how sound changes when the landscape flattens. In the other, the mood is different: Kullberg, Axmith, and Bangsø discuss karate techniques, the American Civil War, sublime sunsets, and perfect G&Ts with dehydrated orange slices.

At a rest-stop coffee refill, Kullberg says: »Everything in the US feels magnified – the landscape, the faith, the grief, the advertisements.« Buene replies that perhaps that’s why the music has to be so direct: »Here you need to believe in something to be able to play.«

The band arrives in New Orleans. Mardi Gras is just over, but glitter still clings to the gutters

Tarmac and jambalaya – Tværs in New Orleans

The band arrives in New Orleans. Mardi Gras is just over, but glitter still clings to the gutters, and purple and green garlands hang tired in the trees. Buene still hasn’t bought a case for his guitar and carries it around in a cardboard box – Fender sticker still attached. But he has written a new song, »Tarmac«, named after »the feeling of car tires against warm asphalt when the haze hangs heavy in 30-degree heat.«

In New Orleans, Buene suddenly disappears from the rented wooden villa.

»Have we lost a band member?« asks Kullberg. »You realise that if two of the singers lose their voices, we can still play?« Buene reappears: »If Kullberg injures himself on his skateboard, we can’t perform.« »Yes, we can,« Kullberg counters. »I can still do it. And play wild solos.« Buene sighs: »I need friends who are not poets. Next time I’m travelling with bankers.«

»There isn’t a single no-sayer in this group,« says Kullberg. Even though Rønsholdt finds it embarrassing when Kullberg does push-ups in the street.

Here in Louisiana everything meets. Traditions brought from afar once blended with African American rhythms. Cajun music grew out of French ballads, mixed with blues, folk songs, and dance steps that still shake dust from the wooden floors of tiny bars.

Meat, poultry, shellfish – everything simmered together like a jam session that never ends

One evening at Café Beignet, Tværs hear a local trio play »Fish Song«. The singer notes drily that »you can pay with jewellery here if you’re short on cash.« In the French Quarter square, fortune tellers still sell truths; voodoo and psychic readings are part of the city’s DNA – served with gumbo and jambalaya.

Cajun cuisine is a mix, a rhythmic compromise between Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, and Southern traditions. Meat, poultry, shellfish – everything simmered together like a jam session that never ends. And Tværs discover that their own music may not be so different from the city itself: eclectic, unpredictable, ramshackle – a sonic jambalaya.

Night falls, the air still as a sugar blanket. Tværs has been here long enough to understand that you don’t play music in New Orleans. In New Orleans, you breathe the atmosphere. And you sing. Everyone does it.

They pack up. The cardboard box with Buene’s Fender comes along to the airport. Now they head to New York.

»Tværs is in no way a pop band«

»It’s My Life« (Brooklyn, NYC)

They ask the taxi driver to turn down »It’s My Life«. »We’re a band and have a concert tonight – we need to concentrate,« says Bangsø.

They study the setlist in the back seat. They debate whether to play amplified or not. The American poet Peter Gizzi has agreed to read a few texts during the concert.

They haven’t talked much about what will happen tonight. »It’s very simple,« says Kullberg. »I write songs. You write songs. That’s it.« He smiles. »After hearing Niels’s Country and everything else, you know he has lots of good songs in him. A producer in Denmark keeps telling him he should write more. I have a very pop-oriented ear, but the songs mustn’t become pop. I keep asking myself: How can I take a song somewhere I didn’t expect? And then I realise that Per Nørgård and Benjamin Britten are always rattling around inside them.«

»Eivind strips his songs to the bone,« he continues. »They have a conceptual foundation in Schubert and Mahler. Mine are closer to Niels’s, and we probably both sound post-genre, while Eivind works more directly within the singer-songwriter tradition.«

»The health authorities have shut the café down. The concert is cancelled«

He shrugs. »Niels is amazing at distorting Americana. It sounds simple, but under the surface it’s insanely complex. Tværs is in no way a pop band.«

Rønsholdt nods: »I’m fascinated by how jazz musicians treat material – with humility, but also freedom.«

Kullberg turns to Axmith:

»We’re figuring out how our aesthetics can mix. And how you can fit into a group of professional musicians – without collapsing. We’ll make you a solo, Bradley – if you dare. I might cut »The Tree«, because I’m not sure it’s right for this group. It’s too jazzy – probably because jazz has been my main gateway to popular music.«

Half the band is sitting at Fiction – a bar around the corner from the apartment – when Axmith calls in with bad news:

»The health authorities have shut the café down. The concert is cancelled.«

Silence. Then they ask the waiter at Fiction whether they might play there instead. A couple of hours later the owner calls: the band that originally was booked has cancelled. Tværs can go on at 9 pm – right after the stand-up comedian.

In the apartment, Bangsø is tasked with making a concert poster. He grumbles. »Listen,« says Rønsholdt, »I’m playing bass. I don’t even know how that happened. The bass changes the sound. I’m inspired by Taylor Swift and Tame Impala.«

He bought the bass just two weeks earlier, shortly before Tværs played their first concert at Elvermose in Nakskov. Lolland feels like a distant planet from the Brooklyn flat. Tonight they play their last concert on American soil. In his room, Kullberg practices a cello concerto by Danish composer Thomas Agerfeldt Olesen, which he will premiere with the Sønderjyllands Symphony Orchestra four days later.

»The Dynamic Danes,« says Eivind Buene as he enters the apartment. Poet Peter Gizzi also arrives to rehearse. They talk about what it takes to create an artistic collective – and how none of them, over the past ten days, has said no to anything.

Gizzi tells how, as a child, he watched the news with his mother – and saw a report about a plane crash. It was his father who had died. His older brother, Michael, soon began writing poems.

»I could see that this was how you processed pain,« Gizzi says. »By writing. It became our way of being in the world.«

With language as an instrument and the rhythm of grief as its grounding pulse, Gizzi performs with Tværs for the first time. After the concert, at the bar, he tells Buene that his Schubert-inspired songs sound as if they could have been written in the ’70s or today: »They’re gorgeous. I’m just jealous,« Gizzi says. The evening ends at Ornithology Jazz Club in Bushwick. They talk about dress codes – and what to do if some musicians don’t make it to the concert at Radar in Aarhus two days later. Aarhus is the finale of the Tværs project.

»I skated through the whole airport with the banjo on my back and made the plane to Billund as the very last passenger. That skateboard saved my ass«

At New York’s JFK Airport, Kullberg and Axmith skateboard through the terminals. Axmith slightly regrets the purchase – New Orleans’ potholes made the board unusable – but it turns out to be his salvation.

»I had twenty minutes in Frankfurt to catch my connection, because the flight from New York was delayed. I skated through the whole airport with the banjo on my back and made the plane to Billund as the very last passenger. That skateboard saved my ass.«

»It was a big hit when we played it in Memphis«

Boyband with jetlag (Aarhus)

Tværs lands in Billund in three different planes.

»We don’t travel together,« Kullberg tells the audience at Radar in Aarhus. »In case we crash, we still have half a band. Now comes »Tell Me You Will Go«. It was a big hit when we played it in Memphis. My cello has jetlag, but that’s fine – we work against the nature of our instruments,« says Kullberg, while Bangsø tunes his guitar.

Among the audience sits Wayne Siegel, professor emeritus at the Royal Academy of Music in Aarhus, who came to Denmark from California in 1974.

»You could call it cultural appropriation,« he says after the concert, “but in a way it’s part of our shared cultural heritage. European rhythmic music springs from American country and so on. It’s brave, and they’ve managed to integrate it so naturally. I myself have an alter ego that plays country and folk. It’s a bit like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde – those two worlds rarely meet. But tonight I felt like saying: why not? You can stretch the definitions. Everything changes, classical music included.«

Epilogue (next stop: Dallas)

Two years after their journey along the dusty backroads of the American South, they are together again. Neither Ida Duelund nor Bára Gísladóttir could join them in Warsaw. Instead, Mariusz Praśniewski has joined the band. After the concert at Opera Warszawska, they drift through the city and end up in a club where the music is far too loud.

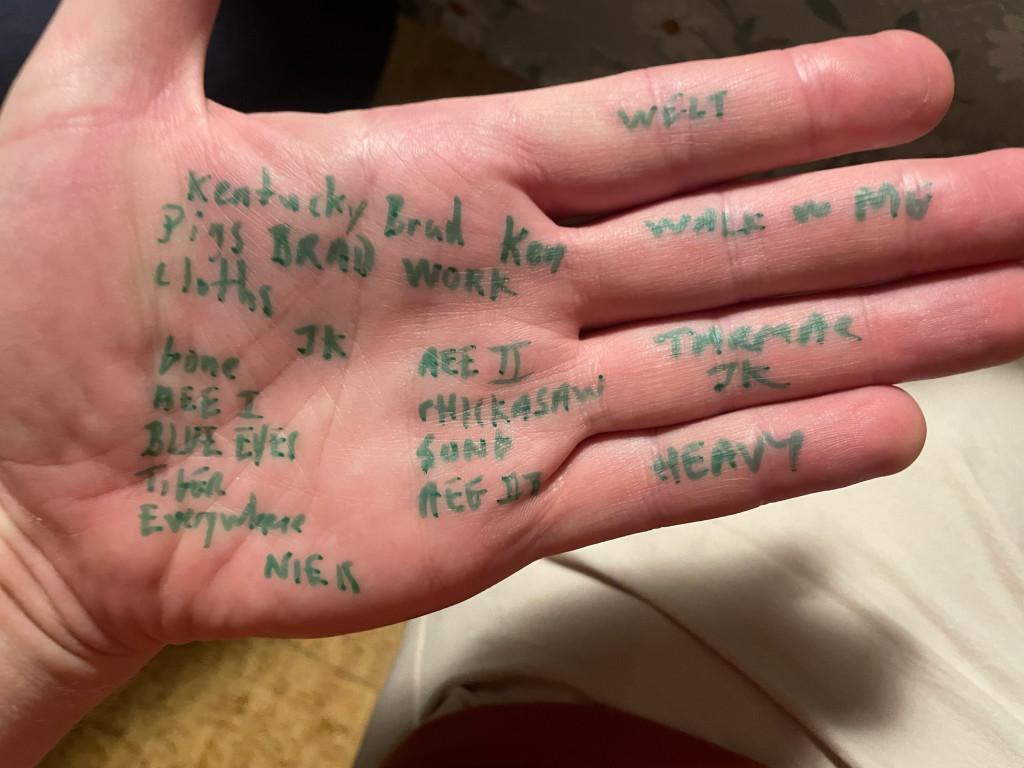

»Totally indie to have the setlist written on your hand,« Kullberg says with a crooked smile. Axmith leans forward and shouts: »Is that Michel Houellebecq sitting at the bar?” A solitary man, bent over his drink, looks like someone in transit between worlds. And why should it be any more unlikely for Houellebecq to go on a road trip to Poland than for five Scandinavians to crash Presley’s barbecue joint in Memphis with an improvised concert? Sometimes you have to get lost to find your way home.

Now they have a band, the friction has vanished, and the journey can’t possibly end here

Now they have a band, the friction has vanished, and the journey can’t possibly end here. In Warsaw they talk about new songs, about the joy of weaving more classical elements into their sound. They ask themselves what Tværs actually is. Maybe a pop group somewhere between Schubert and country. Maybe just five – now six – people who can’t help playing. A collective moving toward something that doesn’t yet have a name. Soon they’ll head out again. This time to Texas. They’re looking for a recording studio in Dallas.

English translation: Andreo Michaelo Mielczarek