Punk is Dead and Opera is Not Feeling Well Either

Until recently, Le Lido on Paris’ Champs-Élysées was a sister venue to the Moulin Rouge, historically known for its revue-style shows culminating in the traditional cancan number, best enjoyed as a dîner-spectacle experience with table service. For decades it had endured the inevitable pressure of conforming to the expectations of the tourists (both French and international) to which it catered, delivering a certain dated postcard image of Parisian nightlife entertainment. After its purchase by a multinational hospitality company and the ensuing makeover and change of staff, the venue reopened in 2022 as Lido2, thus explicitly aiming at a rebirth, with a new offering of Broadway and West End musicals performed in the original English, including Cabaret, The Rocky Horror Show, and Hello, Dolly!.

Mr. Albarn insists that The Magic Flute II is his first »opera«

This new Lido’s Artistic Director, Mr. Jean-Luc Choplin, has had an eclectic career as a manager and curator from the Paris Opera Ballet to Disneyland to Sadler’s Well to the Théâtre du Châtelet and beyond, blurring the borders between so-called high culture and entertainment. Next to more conventional fare (in both fields) Mr. Choplin has honed an aesthetics of crossover, including for instance Pop’pea – Monteverdi performed by a mix of pop and opera singers – or Mozart’s Requiem staged by the famous equestrian artist Bartabas. Such bridges could be argued to be naturally at home at the Lido, where from the 1940s onwards ballet dancers have contributed their training and high-brow touch to music-hall shows. The most paradigmatic and interesting intersection between this history and Mr. Choplin’s trademark is The Magic Flute II: The Curse, An Electro Opera, premiered on March 27, 2025 at the Champs-Élysées venue, with which it shares the telling feature of being named a classic’s »part 2«.

Upon discovering that Johann Wolfgang von Goethe had written an unfinished sequel to Mozart’s The Magic Flute (1791), Mr. Choplin was inspired to assemble a team to execute a variation on this concept. There is no cynicism in observing that Mr. Choplin’s crossover ventures do not rely on mere faith in hybrid forms and the toppling of symbolic hierarchies, but are typically thought out to be attractive combinations of names associated with prestige and/or wide audiences, balanced in the right proportions. To complete the Goethe-Mozart equation, the task of creating new music was offered to Damon Albarn, who from Blur frontman and Gorillaz mastermind has himself branched into an eclectic creator of music thriving in collaborations and crossovers, including stage works such as Monkey: Journey to the West (after the classic Chinese novel), composed for a blend of Western and Chinese instruments and performed in 2007 at Mr. Choplin’s Châtelet.

The musicians standing on stage behind their synthesizers are explicitly thought of as a sonic and visual nod to Kraftwerk

Albarn, Mozart, Kraftwerk, Goethe

Despite creating since then the sung stage works Dr Dee (2011) and Wonder.land (2015), Mr. Albarn insists that The Magic Flute II is his first »opera«. The label certainly takes on a peculiar meaning and weight in association with one of the most performed and influential works in the genre, which in this case has translated into a desire to work specifically with lyrical voices, and the adjunction of artists with more opera know-how, such as librettist Jeremy Sams, conductor-arranger Stephen Higgins, and director Olivier Fredj. There is not much sense in discussing whether The Magic Flute II is, indeed, an opera – a form that has never had a closed definition – but one can’t help being intrigued by the insistence on reclaiming the term. What magic does that old word hold?

Although sequels are now universally acknowledged to be the laziest, most derivative form of money-grabbing in the entertainment industry, one must laud the audacity not simply of trying to add to The Magic Flute, but of doing so despite the fact that it has obviously been attempted before, always unsuccessfully. Goethe himself never finished the draft that inspired the Choplin-Albarn project, which in itself was partly due to the fact that Emanuel Schikaneder, the librettist of the original Magic Flute, had created in 1798 his own sequel composed by Peter von Winter, that failed to replicate the success of the first installment. There have since then been a number of further attempts, including (contrary to what is being claimed in the new version’s PR) efforts to complete Goethe’s fragment and set it to music.

Given these attempts’ lack of posterity, one would be tempted to follow the impulse of Goethe himself, who instead of trying for a sequel proper, eventually used some of the ideas he had developed for his tentative sequel in the more symbolistic sections of his two Faust plays: rather than replicate a form, create something more original and personal.

Were it not for its insistence on being not just a response to Mozart’s work, but also to an imagined concept of »opera« in general, Damon Albarn’s The Magic Flute II held some promise of being such an original, personal work. Mr. Albarn constructed his opus on the sound premise of retaining no Mozartian musical elements other than most voice types (or rather ranges) of the recurring characters, and a short quotation of Papageno’s whistle motive. Composed specifically for the Lido2, The Magic Flute II avoids the pitfall of competing with the original on its own musical terrain, to which the venue would have been as ill-fitted as the composer’s specific skill-set, and instead places the familiar characters on a new backdrop of fully electronic instrumentation.

As a composer Mr. Albarn, if often formulaic, has an ear for avoiding clichés and looking for quirky ways to execute his ideas

This new backdrop is no less familiar or nostalgic in nature, however, as the musicians standing on stage behind their synthesizers are explicitly thought of as a sonic and visual nod to Kraftwerk, but they implement a sound world that takes best advantage of the renovated Lido’s acoustics and technical possibilities. The subtitle Electro Opera, then, is to be taken in its most literal sense: as the juxtaposition of two aesthetics, or of the composer’s imagination of them. What holds them together? Visually, the fact that the electro band is conducted, making the clash of cultures ostensible. Musically, chiefly the vocal expression of the eight lyrically trained soloists which, while exploring and relishing operatic colors, relies melodically on a poppier musical theatre idiom and a (sometimes freely) tonal language sustained, if not curbed, by the permanent synth continuo.

The Magic Punk

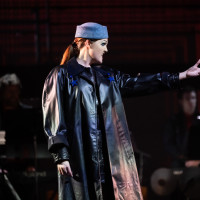

The heavy lifting of articulating the new piece with the original was mostly left to Jeremy Sams’ libretto, with Goethe’s material as a basis. As with any reinterpretation of classical works, the choices of what to discard and what to focus on are bound to be open to controversy, but also made innocuous by the abundance of existing readings. Mr. Sams has retained Goethe’s general double plot: the Queen of Night (Christopher Robson) has had Tamino’s (Alfred Mitchell) and Pamina’s (Elizabeth Karani) newborn child kidnapped and trapped in a sealed box, while Papageno (Hugo Herman-Wilson) and Papagena (Anna Gregg) lament their own childlessness; a new series of trials follows for both couples, and along the way the old authority figure Sarastro (Richard Burkhard) must learn to give way to a new generation. The libretto aptly underlines both its own elements of fan service, intrinsic to Goethe’s fan fiction and to any sequel, and the deeper level of the narrational content, in revealing that the piece really is about passing on our world to the next generation and listening to their voices (the Haendel-Hendrix Academy Choir and the Choir of the Maîtrise des Hauts-de-Seine). Some updates are most welcome, such as dispensing with the villain Monostatos’ purportedly allegorical blackness and with the hotchpotch of numerology and symbolism that Goethe so loved in Schikaneder’s text. (Why precisely Monostatos has to be gender-swapped into a woman (Phoebe Rayner) and the Queen of Night, as the arch-villain, be queered by being performed by a countertenor, on the other hand, remains a mystery.)

The disappointment of hearing him in The Magic Flute II only in a couple of interventions as a Narrator might be shared by more than just his die-hard fans

Conversely, the responsibility of building the bridge between music and text is mostly left to the staging, presumably building on ideas originated in the Sams-Albarn tandem: by treating the space as a night club, director Olivier Fredj (unfairly credited for a mere mise en espace), lighting designer Julien Pichard, and video designer Étienne Guiol bring the entire plot more explicitly into the clubbing world in which an »Electro Opera« feels at home, and the odd mix of stiff operatic blocking and techno sensorial overload, although unsurprising from the vantage point of either world, makes the piece cohesive. The mix is materialized at its most earnest in Missy Albarn’s costumes, that utilize a philosophy akin to 70s British punk fashion in aggregating fabrics and styles, with e.g. leather and tartan creating an ambiguous space between traditional and modern, »high« and »low«. With the caveats inherent to whenever any form of counter-culture is given a clean, neat makeover.

In the same spirit, some elements, such as giving Papageno a hookah as a »magic flute«, or dressing Sarastro and the Queen of Night as flat-out illustration of opposite Western and Soviet blocs, are gimmicky in the old-fashioned way in which opera stagings can be. That is perhaps also because the thought behind the latter, for instance – chaos ensues when the balance between powers is disturbed – feel particularly simplistic at this specific point in time.

It is difficult to make points about the poor ways in which we are managing this world in a musical fable, furthermore one written in short, quasi-rhyming libretto-verse, without an amount of cheesiness: everything ends in a somewhat hopeful eco-friendly chorus, of course. But as a composer Mr. Albarn, if often formulaic, has an ear for avoiding clichés and looking for quirky ways to execute his ideas. The Sunday Times pop critic Dan Cairns once called the Albarn mood »at once utterly forlorn, cautiously optimistic and sonically warm«, and this emotional characterization, most fitting here, might be more accurate than any attempt at finding stylistic unity in his output. The disappointment of hearing him in The Magic Flute II only in a couple of interventions as a Narrator might be shared by more than just his die-hard fans, as that feeling of a voice (in a broader sense) gets easily drowned under the layers of cultural references piling up across disciplines.

Tribute and/or Reinvention

The fact is that it has been almost fifty years since Klaus Nomi blended operatic voice with an electro beat. The casting of countertenor Christopher Robinson as the Queen of Night may be a reference to this, but as such it contributes to the general feeling of a pasticcio evening precisely thriving chiefly on references, as eclectic as they may be. As much could be said about any aspect of the venture. We’ve already had Rent (1996), a modernization of Puccini’s La Bohème, successfully balancing out references to classical opera with contemporary Broadway idiom (and society). We’ve already had Wendy Carlos and Jean-Michel Jarre bringing to the mainstream the blend of classical music and synthesizers and creating a retro-futuristic sound in which timeframes clash. We’ve already had Pink Floyd, Frank Zappa and David Bowie, rock operas, tech fables that sound like each new generation. We’ve already had Louis Andriessen, Robert Ashley, Alice Shields, Tod Machover: composers bringing together the (extended) lyrical voice and the synthesizer, reinventing a function to operatic storytelling in the age of electronic instruments, with technique, vision, and a sense of how these tools ought to influence the way we make music and tell stories. In the light of all this legacy and of its own multilayered nostalgia, it is difficult to see not just what The Magic Flute II contributes to The Magic Flute, but also what it contributes to the medium, whatever that medium is defined to be. Which is at odds with both the work’s ambitions and its message of not blindly revering the past, but using it as a foundation for a new future.

Completing the task this opera gave itself would have perhaps required a team more balanced out between disciplines and artistic cultures; even with the assistance of two arranger-orchestrators (Stephen Higgins and Michael Smith), there is a certain musical clunkiness in the whole and lack of ease in vocal lines in particular that is not simply a stylistic choice. It is not a coincidence that the clubby electro-style sound was so generously round while the opera voices resonated in a reverb that sounded flat and artificial: the gap in expertise was structural to the project itself.

But it is no less worrying to see »opera« – or the nostalgia for 70s »electro« for that matter – being treated as mere superficial aesthetics

Maybe it is the ambition of creating an »opera« that was ultimately responsible for a form of misunderstanding. There is obvious allure in bringing opera voices into other performing arts, as there was for the golden-age Lido revues to integrate ballet dancers: both are quite simply astounding sets of techniques that enriches any palette. But there is a more superficial attraction at play, which reduces »opera« to a connotation of outdated elegance and sophisticated enjoyment, not unrelated to the way champagne is a traditional part of music-hall culture. The Lido (old and new), the Moulin Rouge, and opera houses have in common that they are meeting places for the well-to-do, but also that they sell at a rather high price the promise of an exceptional experience – something that even people with a limited budget will want to indulge in every once in a while, perhaps once in a lifetime, on a special occasion. That is the product. In the process of »reinventing« itself, the Lido2 stands a little uncomfortably between two worlds: the audience is still sitting at tables, yet there is no table service. Part of the transition process is determining with what to replace the previously tokenized celebration of Parisian burlesque.

Such a process is necessarily somewhat awkward, it is natural to all transitions and we certainly are experiencing many at this point in history. But it is no less worrying to see »opera« – or the nostalgia for 70s »electro« for that matter – being treated as mere superficial aesthetics that can be mobilized for the sake of artistic prestige branding than it is to see, as a perfect mirror image, opera houses hurriedly put on musicals (usually with little to no know-how) in order to supposedly open up to new audiences. This doesn’t mean that these forms should be compartmentalized, just that crossover and hybridization require engaging with the Other on a deeper level, beyond our own projections and glamorizations, and certainly beyond commercial and symbolic tokenization.

In this matter Damon Albarn has been a role-model to many when working with artists from multiple and diverse backgrounds. It is unfortunate that he wasn’t given a richer vision of what opera can be as the ultimate space of hybridization. In reality, Schikaneder and Mozart called their Magic Flute something different than the serious Italian word opera: a Singspiel – a motley mixture of voice types and genres, that is not about sounding »high« or »low«, but simply about making a play out of singing, in the vernacular language of their audience. Creating such a Singspiel is something well worthy of the ambitions of all artists who want to tell stories with music, and they certainly should keep trying, regardless of their backgrounds.

»The Magic Flute II: La Malédiction, an electro opera«, Le Lido, Paris, March 27