When the Past Begins to Make Noise Again

One should reject modernity and embrace tradition is a phrase that originated in far-right internet subcultures. Recently, I saw it used by a bakery chain trying to sell me cream buns for a holiday that doesn’t exist.

Returning home from the southern Swiss experimental festival Archipel, I had the impression that the program’s take on contemporary music – especially in its engagement with premodern traditions – felt the most forward-thinking.

The ballroom itself, now the main concert space, retains a haunted quality, as if its floors have absorbed countless waltz steps

Archipel, which humbly and humorously bills itself as a festival for la musique bizarre (April 4–13), is extensive in scope: 50 concerts and performances, eight sound installations, and three artist talks, if my program-counting was accurate. Geographically, however, it’s tightly focused: nearly all events take place in Geneva’s Maison communale de Plainpalais, a 1908 Art Nouveau ballroom turned cultural center. The building is lovingly restored, its winding staircase adorned with plump muses and overripe fruit bowls in salon paintings, and every window decorated with different flower motifs in stained glass – chestnut blossoms, poppies, violets. The ballroom itself, now the main concert space, retains a haunted quality, as if its floors have absorbed countless waltz steps beneath the slightly musty, humid light streaming through skylights.

Sound on the Stairs and Rosin in the Church

The contrast between these lovely surroundings and the self-proclaimed »strange« music performed in them was effective. The various rooms were used in an exploratory and thoughtful way – from Mara Winter’s meditative Renaissance flute playing in tailor’s pose on the staircase, to immersive acousmonium performances experienced lying down in the house’s red-velvet theatre.

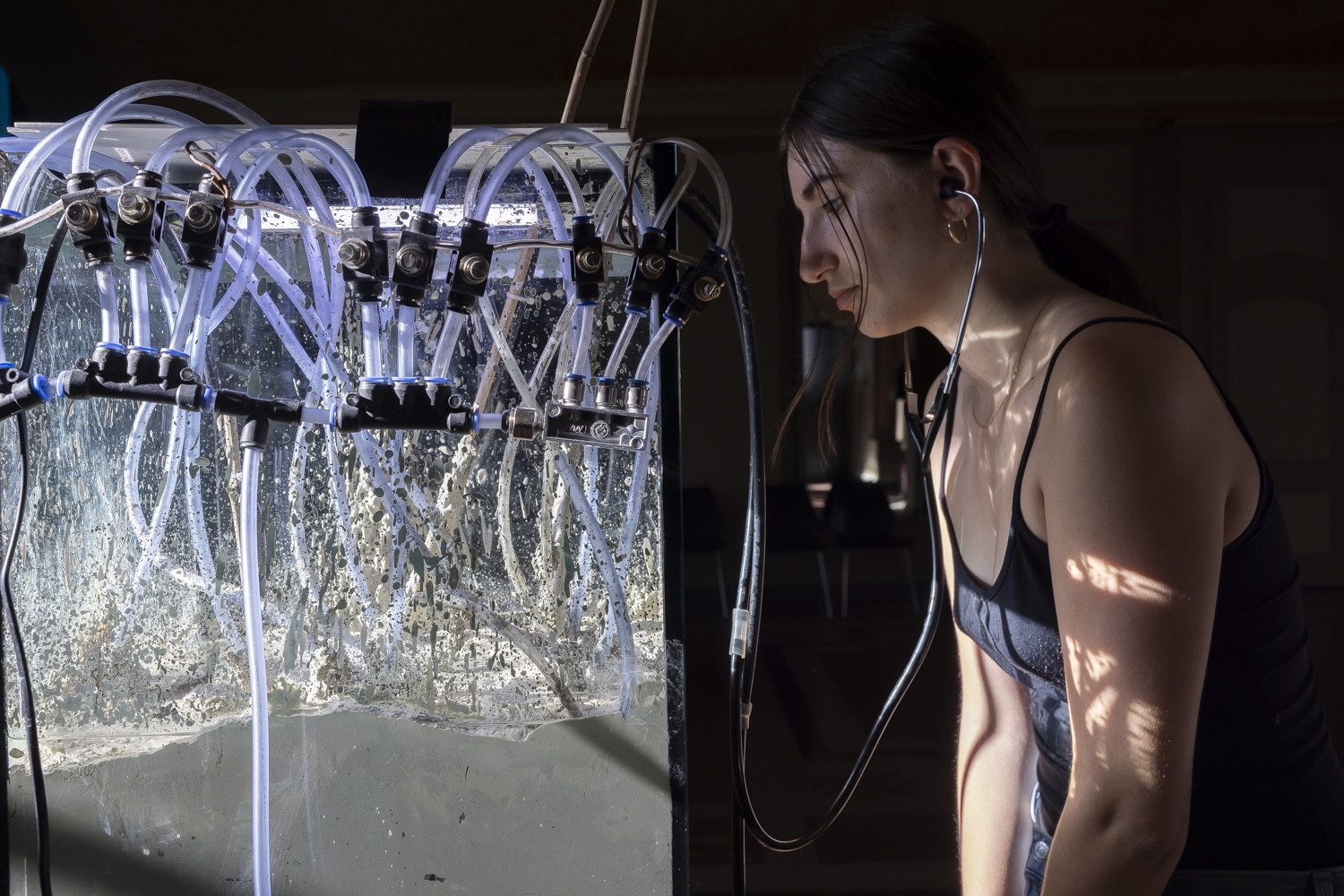

I took the risk – perhaps contributing a microgram of my own bacterial flora to the piece

In one foyer, a plexiglass container filled with mushy, chalk-gray clay bubbled thunderously through a stethoscope. A sign urged me to sanitize the stethoscope before use, but the container was empty, so I took the risk – perhaps contributing a microgram of my own bacterial flora to the piece.

One of the most striking installations was As Low As Possible by local artist Rudy Decelière, set in a church. The piece – a massive, resin-scented mechanical construction of rotating wooden beams – emitted a subsonic rumble from its place on the altar. It felt like a forgotten apparatus with an unknowable purpose, or an eternal machine whose off-switch had long been lost.

Visual art has its Hilma af Klint – but what marginalized composers/occultists might still be undiscovered?

With his humorous listening stations transmitting »healing« electromagnetic waves – including a replica of Wilhelm Reich’s famous 1940 orgone accumulator, which I didn’t dare crawl into – Swiss artist Flo Kaufmann highlighted how counter-Enlightenment thinking, wave therapy, and bourgeois occultism around the turn of the century influenced the emergence of electroacoustic music. Visual art has its Hilma af Klint – but what marginalized composers/occultists might still be undiscovered?

Space, Sound, and Relations in New Music

Archipel features the usual elements one expects at an experimental music festival: family-friendly, sensory-gentle daytime concerts, artist talks, and listening sessions. A standout was the workshop where conservatory students learned to compose for the acousmonium – the speaker-orchestra developed by Groupe de Recherches Musicales at Radio France in 1974, intriguingly contemporaneous with Lee »Scratch« Perry’s spatial dub experiments at the Black Ark Studio in Kingston, Jamaica.

But what sets Archipel apart? There seemed to be a more »Old European« and natural relationship with what is often termed »new music«. As a local violinist explained, conservatory students in Switzerland are required to study both classical and modern composition in depth – perhaps a legacy of geographic and cultural proximity to Darmstadt, the post-war hub for avant-garde music.

»Then, noticing my note-taking, he added: »It’s not a lecture«

This was evident in the presence of Geneva’s respected ensemble Contrechamps, who performed an inventive, if somewhat disjointed, piece by American composer and performer Natacha Diels. Presented sous casque (via headphones), the work was tied conceptually to a proprietary audio technology developed by a sponsoring electronics company. As sound studies researcher Michael Bull has noted, headphones enclose the listener in a privatized sonic bubble – an apt description of the experience, which I personally found uncomfortable and alienating.

In contrast, other elements of the festival countered the traditional bodily alienation of art music. Performers often stood on the floor, not the stage, and the audience could lounge on floor cushions scattered like mossy tufts in the dimly lit hall, limbs and hair poking out here and there – or choose seats on bleachers in the middle of the space.

»I’m using an Old European tuning system to play selections of harp music from ancient Europe«

The Sound of the Past as a Future Resource

As the program suggested, there are numerous links between traditional music and experimental practice. A festival highlight was Welsh harp improviser Rhodri Davies, performing with Scottish drone violist Ailbhe Nic Oireachtaigh.

Davies’ solo portion was extraordinary. He sat behind a large, elegant harp, tilted it gently upright and explained: »I’m using an Old European tuning system to play selections of harp music from ancient Europe.« Then, noticing my note-taking, he added: »It’s not a lecture.« The horsehair strings snapped sharply under his fingers, and from that point on, all our usual associations with the harp – ethereal, semi-spiritual, and gendered – vanished. Davies conjured a weighty, minimal string sound that evoked American primitivism of the 1970s, figures like John Martyn and Bert Jansch, intricate string traditions from India and Persia, or Henry Flynt’s Appalachian anti-art music. The piece emerged from a speculative and imaginative attempt to reconstruct a so-called »bray harp« based on Druidic writings from the 12th century.

It was the buzzing twang of the bass strings – described by medieval Welsh bards as a mirror of the soul – that left me slack-jawed. Nie erhörte Klänge indeed.

This wasn’t just early music’s dream of historical authenticity. It was a speculative approach to sonic archaeology, tapping into forgotten sounds as a way of challenging the still largely unexamined bourgeois, Western musical institution – from an entirely new angle. Similar impulses drove other performances, such as Farnaz Modarresifar and Ensemble Recherche’s gorgeously metallic, ancient-Persian santoor experiments. A kind of musicological reverse engineering: the past as a place from which to imagine a future that isn’t just more of the same.

Historical breadth also surfaced in L’Orgue du Voyage, a concert featuring Ligeti and Bach interpreted by the virtuosic organists Hampus Lindwall, Michelangelo Rossi, and Danish composer Sandra Boss. The setup featured organ pipes of every size and material, constructed by Jean-Baptiste Monnot and controlled from a central MIDI keyboard – creating a primal, electrifying field of sound.

There were also deep dives into materials and instruments, such as Many Many Oboes, where four oboists explored every iteration of the somewhat nasal-sounding instrument. Based on the title, I’d imagined something like Glenn Branca’s symphony for 200 electric guitars, so the small oboe circle was a slight letdown – though maybe unfairly. The final piece was delightful and silly: rubber hoses attached to oboes blowing into water containers, producing delicate gurgling sounds.

After a quick internet dive into oboe lore, I wondered if this was a nod to the tradition of soaking and trimming oboe reeds – since, like ballet dancers break in their pointe shoes, oboists wet and prep their reeds to coax the right vibrations. Instruments are, quite simply, tools.

A Festival on a Human Scale

Throughout, the festival also embraced subcultures of collecting, fandom, hyperfocus, and DIY. A refreshing counterpoint to the institutional and grant-funded framework that usually dominates art music.

Festivals are exhausting. But their magic lies in the dream of a life filled with art and sensation

There was an open zine workshop with a copier and supplies for on-the-go documentation. A pop-up art music bookstore offered everything from niche zines to academic volumes. I browsed a conversation between Tony Conrad and German critic Diedrich Diederichsen and flipped through a book on children’s musical folklore, while tempted by a ludicrously thick Cornelius Cardew biography and a cassette of »healing electromagnetic vibrations«. Wonderfully nerdy.

Festivals are exhausting. But their magic lies in the dream of a life filled with art and sensation: What if every day could be like this? In Archipel’s case, the execution was seamless – at least from an audience perspective. With everything housed under one roof – from food to concerts – there was no need to rush or strategize against queues. Instead, one could use the generous breaks to chat, immerse oneself in installations, or simply retreat for a while. A more humanly sustainable way of engaging the public than the conventional firework display of constant spectacle, which often overwhelms the senses. Moderation in everything – such is the way of Archipel.

Archipel, Geneva, April 4–13

English translation: Andreo Michaelo Mielczarek. Proofredading: Seb Doubinsky