Universal Music with Local Truths

On the Faroe Islands, opera is a contemporary art form and an intensely national one – more inextricably bound up in ideas of nationhood than anything happening right now at La scala. You can write that unequivocally, when there are only two Faroese operas to discuss.

The second of them has just been born. Regin smiður arrived amid the deep snow of a Klaksvík Christmas in the final days of 2024. Its predecessor, also composed by Sunleif Rasmussen, dates from 2006. Í Óðamangarður adapted a story by the nation’s bard, William Heinesen. It was deemed »a work of haunting originality and beauty« by a critic dispatched to the North Atlantic review it, all the way from The Times in London.

Two decades later, music stands with knitwear and candle-smoke waterfalls as one of the Faroe Islands’s most recognized commodities. Eivør’s voice unfurls itself over film and gaming soundtracks and Rasmussen’s scores are broadcast by BBC orchestras. Also new – very new – is Varpið, the Faroese answer to Reykjavík’s Harpa: a hybrid of proscenium theatre and shoebox concert hall whose metal-box housing leers at an angle over Klaksvík’s main street, like part of a satellite fallen from space.

Rasmussen insists there was only one place fit for his second opera, and this was it. Acoustically, you can hear why

For all that, the Faroese music scene feels entirely unchanged. The nation’s musical traditions are ever-constant, ever-true – passed down through generations, rooted in folklore, betraying the silhouette of the European melodic tradition but shot-through with the wildness of the place. That feeds into Eivør’s rock ballads and the nation’s contemporary doom metal scene as much as it does Rasmussen’s frequently stringent scores. Music, like sport, remains a community pursuit here – mostly free from the trappings of a »music industry«, however efficiently the dynamic Kristian Blak has got the country’s astonishing musical ecosystem working like a micro economy.

Varpið is among the initiatives that will ensure Faroese citizens, as well as tourists, benefit from the nation’s extraordinary and exportable attitude to creativity. The building was officially finished in April 2024. Rasmussen insists there was only one place fit for his second opera, and this was it. Acoustically, you can hear why. Physically, the auditorium is smart, cozy and atmospheric.

Rasmussen isn’t so bothered about Wagner’s pilfering of tales that belong, in part, to the Faroe Islands

A big deal

And so to Regin smiður (Regin the Smith): wholly Faroese, sung in the language, built on the quatrains that form the country’s literary DNA, literally interwoven with the sight and sound of the chain-dancing tradition that is unique to this place. At the same time, Regin smiður knocks at the very heart of the European opera tradition by reclaiming a story made famous by Richard Wagner. It uses the same stanzas that fed Wagner’s source for his Der Ring des Nibelungen – specifically, the adolescence of Siegfried, his forging of the sword Nothung and slaying of the giant Fafner.

When Iceland was forging its own notated music culture under Jón Leifs – half a century before the process now well underway on the Faroes courtesy of Rasmussen – Leifs railed at Wagner’s appropriation of Norse mythology. The Icelandic composer’s three oratorios based on the Edda represented a conscious effort to wrest ownership of the stories back from their hijacking by Wagner in the Ring, a work dismissed by Leifs for its »terrible misunderstanding of the Nordic character« (it hadn’t crossed Leifs’s mind that Wagner might have been aiming for something more universal).

Rasmussen isn’t so bothered about Wagner’s pilfering of tales that belong, in part, to the Faroe Islands. Indeed, Regin smiður comes complete with its own quasi-Romantic, Wagnerian denouement – in the case of this first production, a literal new dawn (as seen on Aurélie Remy’s projected films) that forms a striking parallel to the dramatic conceit that closes Götterdämmerung.

That the premiere was a big deal here was manifest in the decision by Föroya Bjór, based in Klaksvík, to brew its own commemorative ale for the occasion

That might just be the closest Regin smiður gets to Wagner’s philosophical realm. Whether or not it’s a »reclamation«, Rasmussen’s opera gives us the story as it sits in the ballad of the »Nibelungnlied« and its incarnation as the Faroese »kvad« »Sjúrðarkvæðini«, sung on these islands for at least 800 years and probably known intimately by many in the audiences who sold out four shows at Varpið and necessitated the adding of a fifth (the performance I saw). That the premiere was a big deal here was manifest in the decision by Föroya Bjór, based in Klaksvík, to brew its own commemorative ale for the occasion.

The opera’s saga-like narrative clarifies how and what Wagner adapted for his own purposes in Siegfried. We are told of Hjørdis (Sieglinde) and Sigmundur (Siegmund), the birth of their son Sjúrður (Siegfried) after the latter’s death in battle, and the boy’s growth into a young man. Sjúrður is determined to avenge his father’s death and has a sword, Gramm, forged by the titular blacksmith, Regin (Mime). Off he rides on his chosen horse, Grani (Grane) to slay the giant worm Fávnir (Fafner) whereupon he meets Nornagestur (Wotan/The Wanderer) who advises him on trust. Eating Fávnir’s heart allows Sjúrður to understand birds (The Woodbird), who again warn him of Regin’s murderous intent. Tantalizingly close to Wagner, and yet so far from the polished-up corporate squabbling of the Ring.

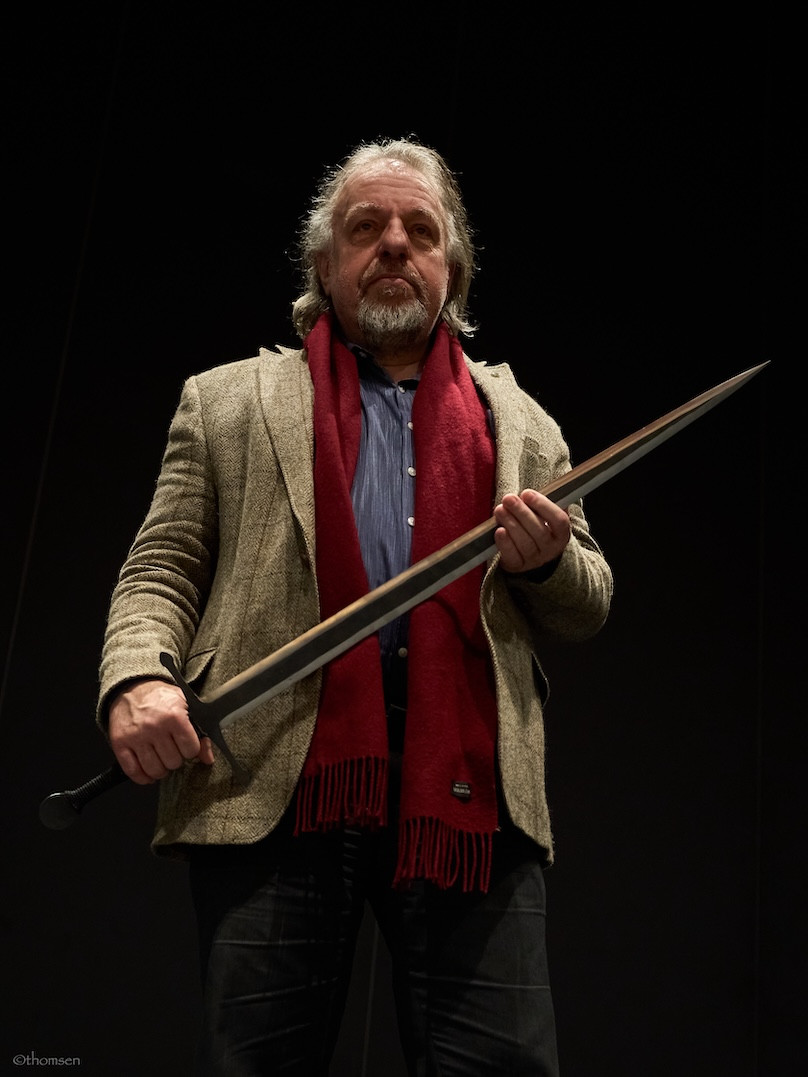

All of this was recounted in the third person, according to the quatrains, by a single singer – in this case, the internationally working Faroese bass Rúni Brattaberg. He came to embody the characters of Sjúrður and Nornagestur but two dancers, Rannvá Guðrunardóttir Niclassen and Sigurður Edgar Andersen, became others, including Regin the Smith himself, via Lára Stefánsdóttir’s eloquent and quirky narrative choreography. Remy’s imposing video art brought modernity, humanity and a sense of the epic to the small theatre – much of the latter coming from Michel Hallet’s drone footage of the Faroese landscape, its 45-degree cliffs, snaking fjords and glinting waters. The Faroese new music ensemble Aldubáran - trumpet, trombone, piano and two percussionists playing all manner of instruments (often two at the same time) – was conducted by Norbert Baxa.

The instrumental music underneath clatters, bristles, mourns, wails and frenzies (the story is no picnic)

Droll and blunt as the Faroese weather

On the one hand, Regin smiður was tremendously ambitious in its Gesamtkunstwerk conceit: incorporating of song, dance, theatre, film, instrumental music, live electronics and pre-recorded performances. On the other, the entire enterprise knew its means and its limitations and was characterized by a constant focus: on text and story. Perhaps the guiding hand of the National Theatre of the Faroe Islands (Tjóðpallur Føroya) was to thank for that.

From Rasmussen’s perspective, that focus was dictated to some degree by the structure of the quatrains. As in all manner of North Atlantic and Finno-Ugric folk traditions, repetition is central. Each of the nine sections is introduced by the relevant chain dance – performed, here, by Klaksvík locals on film, projected in various states of refraction onto the stage’s back wall. The looping music Brattaberg sang thereafter is based on the same melodic material.

The instrumental music underneath clatters, bristles, mourns, wails and frenzies (the story is no picnic) before entering its final luminous state. But even without Brattaberg’s chant-like incantations tethering it, the ensemble’s complexity is rooted in simplicity – characteristic of Rasmussen’s signature way of speaking unequivocally of his country without patronizing or simply rehashing. The score launches with superimposed iso-rhythms that form their own melding, fertile patterns.

Even for someone who has never chain-danced, the piece carries with it the sense of that activity’s tight-bound humanity and communal experience

This, of course, is echt-Rasmussen – the composer’s ability to command the attention with music apparently as droll and blunt as the Faroese weather but which stealthily enters more sophisticated states. This echoes the composer’s previous refracting of tunes from the chain dances or Faroese hymnal, making them his own while preserving their identity and integrity (one thinks of his 1992 work Sig mær hví er foldin føgur) and in this case, adapting them to a leitmotif system which is the score’s most obvious musical salute Wagner (Leifs would have been furious). Brattaberg sang with a rawness and straightforwardness that reflected the material but with flashes of warmth. Despite pages hovering around the same low tessitura, he was mostly able to adapt to the mode of the storytelling and the hue of its content. He assuredly formed the drama’s centre of gravity even as plenty happened around him; his multifaceted interactions with the dancers Niclasen and Andersen didn’t ever break the dramatic spell (credit to them too – and Niclasen’s portrayal of the bird deserves special mention). Something of Brattaberg’s demeanor, in a contemporary suit and tie, bound myth to reality.

That crystallizes one of Regin smiður’s biggest successes. The sprawling elements of the stage drama were assiduously bound together by director François de Carpentries and Rasmussen’s music never got in the way of storytelling or the feeling of »collectivity« vital to the work – collectivity for the performers, but surely for the Faroese in the audience too. Even for someone who has never chain-danced, the piece carries with it the sense of that activity’s tight-bound humanity and communal experience.

Local truths

Rasmussen’s music used its concurrent planes of activity to exist both directly and surreptitiously. There is an epilogue (overly long, and in need of some assiduous cuts), in which Brattaberg sang off-stage while the dancers seemed to suggest Sjúrður had discovered not fear (as in Wagner) but love. Here brass instruments trace ascendant lines that are electronically processed into echoes in real time. Each of the nine filmed chain-dances seemed to become more blurred and indistinct as the performance proceeded: current reality becoming eternal myth; past legend informing all our futures.

That might be a Wagnerian idea, but Regin smiður is vitally different to Wagner: a story whose universal truths are far more locally aligned and defined – a piece in which we strongly sense the residue of a tight community for whom storytelling has plenty of real-world implications. In Klaksvík’s new theatre – maybe even in Copenhagen, where this new work would be a good fit for the summer’s opera festival – that seems more than appropriate.

Varpið, Klaksvík, Faroe Islands, January 5, 2025