Alien Frequencies

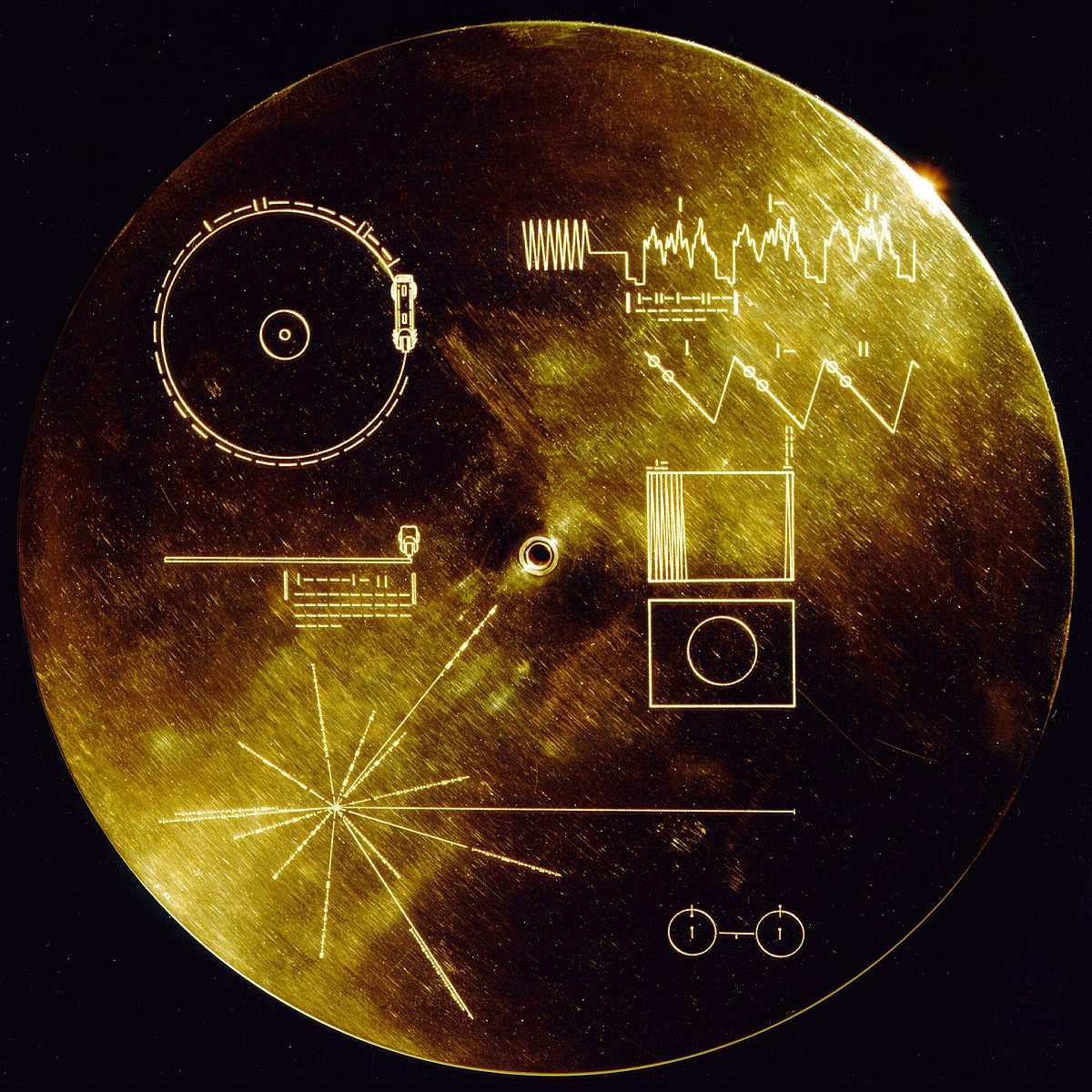

NASA has made it possible for Earth’s musical culture to be evaluated by aliens. The Voyager spacecraft, launched in 1977, contained a golden record that, alongside multilingual greetings and an attempt to establish a common basis for communication, included a mixtape for off-world audiences. European classical music is heavily represented: the selection opens with a recording of Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto no. 2 by the Munich Bach Orchestra and is followed by selections from musical cultures from around the world. The American contributions include Chuck Berry’s »Johnny B. Goode«, Louis Armstrong and His Hot Seven’s »Melancholy Blues«, and Blind Willie Johnson’s »Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground«. The mixtape has always been a format with which to swagger and seduce, meant to project both front and vulnerability. How, though, might we interpret a sampler from another star system; what might its effect on us be?

The Martians are slender and excessively intellectual, their music is elaborate and conceptual

The first English-language fictional account of an interplanetary music recital seems to be in Robert Cromie’s novel of 1890, A Plunge into Space. H. G. Wells made the aliens hostile and predatory in his better-known novel published eight years later, The War of the Worlds, but both stories are premised on the idea of Mars being an older and decaying planet compared to the youthful Earth.

In Cromie’s novel, explorers from our planet contrive a device to send themselves into space and the nearest planet thought to be inhabited. On arrival, the visitors discover a civilization that is far more developed than that of late-nineteenth century Europe but on the verge of collapse from the over-refinement of its culture and life-systems. There are luxuriant and fragrant flowers everywhere, the Martians are slender and excessively intellectual, their music is elaborate and conceptual – »visionary unreality«, the visitors judge it.

Look back

The novel puts music in the mix of cultural forms that reflect human progress and implies a need for cultural refinement to be balanced against the reinvigoration that younger cultures (and adventures in space) can afford. Less than a century later, the playlist on NASA’s golden record seemed to project similar concerns: if listeners (off-world or in the Soviet Union) found the mix overly cerebral based on the classical selection, might they be encouraged to invade our decadent world? To offset the message of (over-)refinement there are the energies of rhythm and blues, and Chuck Berry’s electric guitar.

It is absurd, obviously, to imagine that aliens will receive our music and be humanoid to the point of sharing a value system that interprets it along a cultural axis that runs from energy through sophistication into decline. But science fiction has always provided a mirror-function, allowing us to look back at ourselves, capable of both projecting our technological fantasies of better futures into space and reflecting human culture and beings from a remote perspective that leaves them looking… strange. The example of NASA also reveals a disquieting distribution of values along lines of race, but the imagination of interplanetary music can be arranged differently, in ways that do not project American exceptionalism into space. We can conceive transmissions received rather than broadcast.

Imagine a smear of light across the sky at night, some remarkable damage to a field somewhere, and suited investigators from an unpublicized branch of government finding a copper cylinder half-buried in the soil in the bottom of an impact crater. Once safely unscrewed it is found to contain some superseded media, say a DAT tape, with a playlist of off-world music: music by Sun Ra and his Arkestra (»Have you Heard the Latest News from Neptune«), Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (»Starman«), Parliament (»Mothership Connection (Star Child)«), Lee »Scratch« Perry (»Step in Space«), and a track from Aleksi Perälä’s Colundi Sequences (»UK74R1405036«). In the origin stories of these artists and their music, we already have off-world music in our devices and on our stations.

The theremin and other eery machine-noise have long been used to establish a soundscape for contact between the modern world and others beyond it

Brothers from another planet

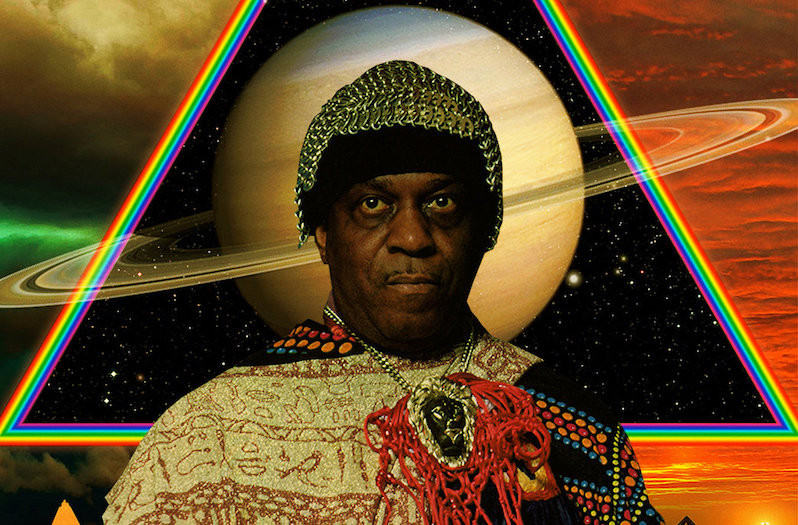

John Corbett makes Sun Ra first of a cosmic fraternity that he discusses in his book Extended Play: Sounding Off from John Cage to Dr. Funkenstein. In a synoptic chapter, »Brothers from Another Planet: The Space Madness of Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry, Sun Ra, and George Clinton«, he makes the intriguing point that there doesn’t seem to have been any conscious influence between them. In one of his interviews, for instance, George Clinton runs through a roll-call of American music but says he only heard about Sun Ra’s earlier space flights long after Star Child and Dr. Funkenstein appeared out of the P-Funk Mothership.

Corbett details the projects and some of their common features (outlandish costumes and props, creative use of new audio technologies, elaborate stage shows) but he doesn’t pursue the question why these (and other) musicians transposed the settings of their musical projects into outer space. He does, however, put these personae and practices into the political and business context of the exclusions of artists of colour from mainstream recording and performance possibilities.

The exploitation of the newest technologies of music production and performance, and their incorporation into musical science fictions of and beyond race, is a contrarian technological futurism. (The authoritative account of this subject is Kodwo Eshun’s More Brilliant than the Sun: Adventures in Sonic Fiction, which is out of print but findable online.) The sounds of the theremin and other eery machine-noise have long been used to establish a soundscape for contact between the modern world and others beyond it: the theremin features heavily in the soundtrack to Rocketship X-M (1951) and Delia Derbyshire arranged the distinctive Doctor Who theme (1963) using techniques developed in the BBC Radiophonic Workshop.

Sun Ra and Yuri Gagarin

The tonal range of science fiction, from the utopian to the uncanny, is established by the estrangement of machine technology as unfamiliar noise. This general relationship of sound to the imagination of space should not make invisible the specific optimism attached to the space age by some musicians in terms of race politics.

Duke Ellington wrote an essay, »The Race for Space«, in 1962, in which »attempted to press the future into the service of black liberation« – an undertaking that Eshun links to Martin Luther King’s nearly contemporary pamphlet »Where Do We go From Here?« John F. Szwed’s biography of Sun Ra brings together Sonny’s sense of vindication when Yuri Gagarin became the first human in space (having been writing music of the space age for thirty years already), with his alarm at the news, less than a month later, of attacks on civil rights activists in Alabama, where Sun Ra was born as Herman Poole Blount in 1914.

Sun Ra recorded albums with titles such as Sun Ra Visits Planet Earth throughout the 1950’s but most of these were released in the 1960’s on Sun Ra’s own Saturn Records label; likewise, while an early adopter of new instruments, such as the electric piano in 1955 (Ray Charles was another), these audio technologies provided him with means to foreground techniques of musical estrangement he had been developing already, for instance the left hand playing phrases from songs the band hadn’t yet started playing.

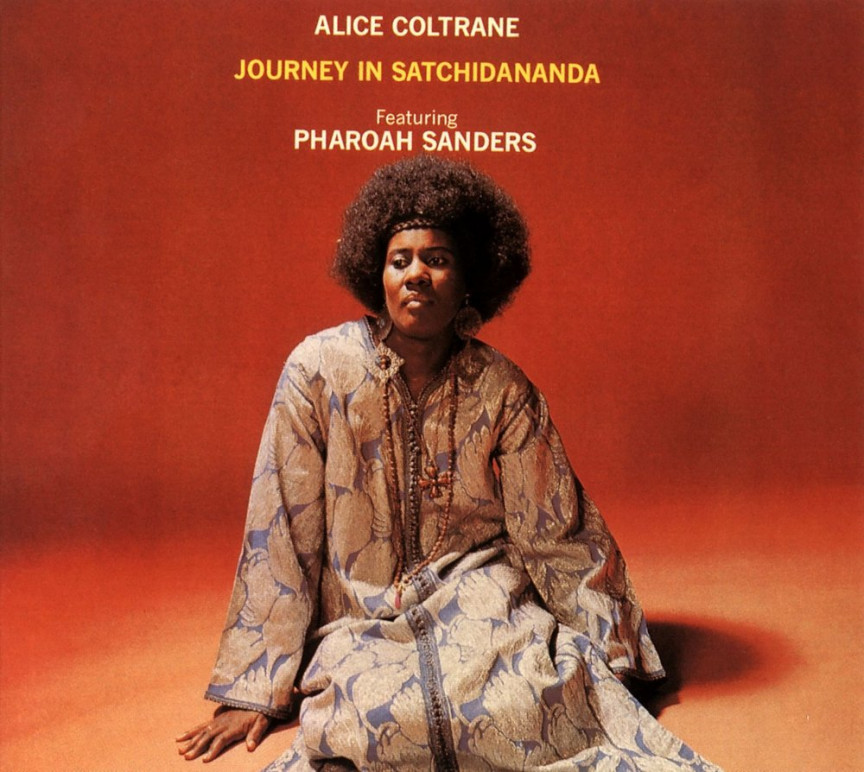

Sun Ra may have been the earliest of an identifiable cultural group described retrospectively as Afrofuturism, but as is always the case when viewing cultural histories, especially one that plays so much with history, an account of Afrofuturism needs to leave the doors open. Jayna Brown’s book Black Utopias: Speculative Life and the Music of Other Worlds draws an elliptical line between nineteenth-century African American black female preachers, Alice Coltrane’s marathon sessions of musical improvisation as mystical devotional practice, the estrangement of life in Octavia Butler’s science fictions, and the altered destinies of humanity that Sun Ra envisioned.

Utopian aspirations

Although Brown doesn’t make the time connection explicit, the communal, ascetic houses in New York and Chicago where Sun Ra’s Arkestra musicians worked in preparation for performance recall the utopic communities where Jarena Lee, Zilpha Elaw, and Rebecca Cox Jackson developed ecstatic practices for – as Lee called it – »melting time«.

At first glance, or listen, the Colundi project seems to join this history of space music with utopian aspirations. It has an off-world origin story of musical sources and retunes pitch to alien frequencies. Grant Wilson-Claridge and Aleksi Perälä are the two names most associated with the Colundi project and have worked together previously at Rephlex records, of which Wilson-Claridge is the founder and on which Perälä has released under the Ovuca and Astrobotnia monikers. The Colundi releases consist of a series of sound frequency sets, or »sequences«, that diverge from conventional scales and tones of western music. Retuning instruments is not new and has historically been inspired by both indigenous music cultures and mathematical calculation, but the Colundi sequences are said to be frequencies and intervals that heal the body and spirit, received from off world by Wilson-Claridge who then passes them on to Perälä, who releases them as »bubbly, beatific post-rave tracks peppered with curious melodies and a general sense of cosmic optimism«.

The first Colundi collection was published in 2014 as The Colundi Sequence Level 1 on Clone records and other releases continued sequentially up to at least Level 17 (2019), sometimes on a variety of media formats that have included mini-discs, DAT, and even a wax cylinder. Reddit posts from this period of releases (among the GIFs and Aphex homage posts) ask, sometimes tetchily, when Wilson-Claridge and Perälä will make these sequences of universal understanding generally available. The publication of Colundi volumes by various artists in the last two years (for instance Colundi every0ne (An Enchantment of Sonic Spells part 1) in 2020) suggests that the frequencies have finally been distributed as the Colundi logo remains in use. It’s difficult to get a more detailed picture as nobody involved is reachable and the Colundi website (colundi.net) has presumably been abandoned and is now populated by Indonesian betting advertisements.

Without verification, I’m only able to put together a sketch of the Colundi mythology from discussion threads and conversations with friends who were close to the project: Colundi is said to derive from pre-western mysticism, the Egyptian pyramids in particular. The name »Colundi« is taken from a small village in Somalia that has a settlement history dating back to the first civilization in Mesopotamia and is one of several sites of ancient alien encounter.

Repair a broken world

The Colundi project invited crowdsourcing, sold releases on a pay-what-you-want-to-contribute basis, and claimed to be buying plots of land in remote locations in Scotland, the US, Indonesia, southeast Africa, and Cornwall – the original home of Wilson-Claridge’s collaboration with Richard D. James (aka Aphex).

Stimulant-free musical and spiritual gatherings were organized in these locations to establish a cosmic energy network that would contribute to the healing of the world. I can’t see the use of trying to establish what parts of this or the other projects are serious, a wind-up, or dangerously cult-like. Aleksi Perälä plays to discerning audiences all over the world and definitely seemed sensitive to frequencies most of us aren’t. He came to Poland in winter 2001 to play a mini tour that I organized in a former life and shortly after arriving from Finland he described hearing the northern lights, not as a sound exactly, but as an auditory experience, nonetheless.

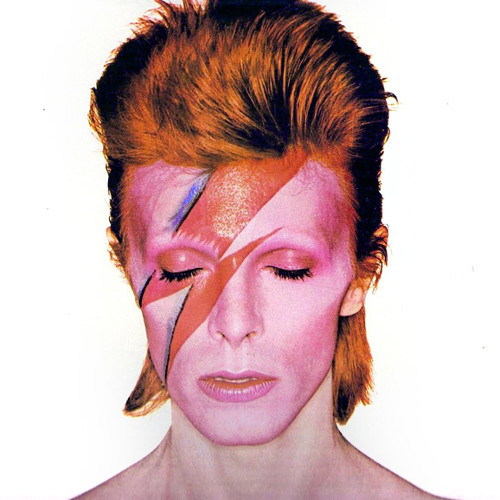

Like Alice Coltrane’s spiritual practices of musical rehearsal, Sun Ra’s mythology and messaging, David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust concept album, George Clinton’s mothership personae and stage-show, the Colundi project aims to repair a broken world. All of these formed something like esoteric communities (some more earnest than others) and established scenarios for channelling beyond-earthly musical transmissions in order to reset social and musical relations in the here and now. But this assembly mixes the politics of its star-men and women too casually.

Establishing alien origins has been a deliberate tactic of racial dis- or re-identification for artists gathered under the term Afrofuturism. In Eshun’s book Brighter than the Sun he describes the ways African American artists have drawn on alien energies as »a rejection of any and all notions of compulsory black condition«. In other words, the techniques of the sample, remix, and drum machine allowed musicians to create music that was no longer circumscribed in any definably black musical culture and history, and so open up future histories that were not always chained to the legacies of violence, poverty, and incarceration of African American experience.

When Sun Ra and Alice Coltrane returned to Egyptian mythology, they were implying something like alternate history, in which legacies of African science and civilization exist in direct lineal descent with the modernity and technology of the twentieth century. In comparison, it’s not clear what historical events are being displaced when Bowie presents as a Ziggy, except perhaps an environmental collapse whose victims are, however, undifferentiated (»We’ve got Five Years«).

Robots talking about AI

Rather than re-routing history from ancient Egypt into some alternative future in which slavery is bypassed, Pyramids function as a sort of abstract architecture for the Colundi project, whose symbols and diagrams are more harnessed to an alternative physics that often comes close to both conspiracy theory and technological utopianism. Several of the Colundi releases open with robot-voices talking about AI and singularity, topics – whatever your interest or opinion on them – whose celebrants tend not to be overly pre-occupied with social justice or historical inequality, except as baggage that technological solutions (and perhaps the right recombination of tonal frequencies) will magically disappear.

Science fiction, as such, is recast in the light of Afrodiasporic history

Kodwo Eshun returned to the subject of Afrofuturism in an article published in The New Centennial Review in 2003 and supplemented the temporality of his book on Sonic Fictions with a bone-shaking revision. Narratives of removal to off-world settings render into sound more than achieved escape velocity; they transvalue the common experience of abduction by a foreign power and relocation to America, a hostile and alien environment.

The conventions of science fiction, marginalized within literature yet central to modern thought, can function as allegories for the systemic experience of post-slavery black subjects in the twentieth century. Science fiction, as such, is recast in the light of Afrodiasporic history.

This audacious framing of Afrofuturism establishes a concrete meaning and a set of historical methods to a collection of artists and writers who can sometimes seem only loosely connected. And it is an entirely accurate description of musical ensembles who explicitly adopt legacies of slavery as their own origin stories, for instance the Detroit techno collective Drexciya that he cites, who present as the mutated, aquatic descendants of pregnant women thrown overboard on the Middle Passage from west Africa to the Americas. Eshun’s account of Afrofuturism explains the amenability of this frame to renewal and reappropriation in the musical front of the political struggle for equal rights in racist America. The day this article was finished (17 February 2022), Moor Mother performed with the Sun Ra Arkestra in Carnegie Hall.

Starman with a message

The serious content of these off-world adventures in music alert us to who and what we put together in groups of common form or purpose. Are we listening to a completely different station when we tune into the off-world programme of Ziggy Stardust and David Bowie’s character in The Man Who Fell to Earth, who seems an early try-out of his persona of the »thin white duke«? The role Bowie plays in Nic Roeg’s frustrating film of 1976 pre-dates Ziggy Stardust, being based on a novel by Walter Tevis from 1963. Even so, the sparse storylines of both Ziggy Stardust and the humanoid »Jerome Newton« are oddly compatible and, interleaved, form a vaguely coherent story about inter-planetary music and technology.

In »Five Years«, the opening track on The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust (1972), humans learn of the apocalypse that is sweeping towards them. In »Starman«, young British listeners manage to tune in to »hazy cosmic jive« on the terrestrial televisions that pre-figures the arrival of the Starman who brings a message of salvation, tempered by the fear that he’ll »blow our minds«. In Roeg’s film, the doomed environment is the starman’s home planet, with the main narrative on Earth intercut with scenes of a drought-ravaged planet and the death of his family group. On Earth, he takes the identity of a British inventor who patents a number of alien technologies, which he forms World Enterprises Corporation to market. He becomes immensely rich but descends into an alcoholic, TV-addicted stupor.

He fails to use his wealth to return to save his family and surrenders to the dissipation of western consumer culture. At the end of the film he has recorded an album of messages that he hopes will be received by anyone remaining on his home planet to receive them.

Human stories

I enjoy the clean wash of optimism in Aleksi Perälä’s music, as well as the unearthly combinations of texture and pitch (thought without a SubPac tactile audio system recommended for a full-body, immersive experience). But I think that its only historical direction is into space and some purified consciousness that doesn’t appeal to me. Bowie’s two science-fictional outings add up to a story set along the same trajectory, even if they embrace more appealingly queer and sleazy relationships between aliens and earthlings that end with an anti-utopian judgment against technologies of communication.

Neither offers the weird encouragement of Sun Ra’s albums, which, however difficult on the ear they might be in places, always loop back to this planet and suggest other endings to its human stories.