How we learned to love repetition

If the cultural landscape of the last hundred years had to be explained in headlines, one of them would read: »How we learned to love repetition«. Because yes, we have had a complicated relationship with what is otherwise such a large part of human everyday life.

The Frankfurt School warned against repetitive music, discouraged by machine-like crowds marching in time. Pop, jazz, anything that wasn't Webern: Yikes. Others called for a fight against art that seemed so reproducible that it was barely distinguishable from the abundance of goods pouring out of factories. American minimalism with endless patterns that only just evolved? Thanks but no thanks.

Freud talked about regression and the death drive. Soldiers who returned home from war and kept reliving the same traumas. Adorno feared a society so hypnotized by the possibilities of technology that it became blind to the horrors that the machines brought in practice: the holocaust, the atomic bomb, total barbarism amid the triumph of enlightenment.

When techno swept over the youth of the 80s and 90s, we stared the machine in the face and saw that it wasn't so different from ourselves

But then, quite slowly, the repetition nevertheless won its admirers in the cultural elite. The hippies loved Terry Riley, the discotheques discovered that machine beats could lead to personal liberation, and when techno swept over the youth of the 80s and 90s, we stared the machine in the face and saw that it wasn't so different from ourselves.

It was the short trip of a century. Fortunately, the German media critic Tilman Baumgärtel has written a longer version focusing on one of the most central phenomena that has shaped our musical culture since the Second World War: the loop.

The book is called Now and Forever, with the subtitle: Towards a Theory and History of the Loop. As someone who once thought this was the book I was supposed to write myself, I can only say that I am glad Baumgärtel did it. It is, as they always say in the newspaper Information in the absence of stars to hand out, excellent.

Berghain and Philippine fireflies

When I handed in my thesis ten years ago, it was such a clumsy title that even the professor at the later graduate reception stumbled over the words. The subject was repetition, my focus was the minimalists who in the 60s were the first to put the repetitive expression at the very forefront of music. La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, Philip Glass – the fab four of art music.

The repetition: a kind of metaphysical force that makes everything hang together in a vortex of mirrors, echoes and endings that are beginnings

My idiotic, academic-snobbish subtitle promised to zoom in on »anti-teleological and desubjectivating tropes« in the reception of the four Americans. It probably worked, but I knew there was much more to say on the subject. What I could not imagine was that it could be said as poetically, knowingly and surprisingly as Tilman Baumgärtel does in Now and Forever.

In the preface, he stands in front of the Berghain in Berlin on a Sunday night, surveying the living building booming with techno. Inside, he sees the strobe's snapshots, gets memories of a coal-burner Metropolis at the sight of the steel staircase and experiences how everything becomes one great, eternal machine while time dissolves itself.

On to Tokyo and the world's busiest traffic lights, where Baumgärtel loses himself in the traffic lights, the advertisements, the day, the year – all the repetitions that make everything around him turn into flickering lights like the fireflies he seeks out in the last chapter in the Philippines and falls in love with in for their common pulse. The repetition: a kind of metaphysical force that makes everything hang together in a vortex of mirrors, echoes and endings that are beginnings.

But the repetition is also a very concrete phenomenon, which he links with his focus on the loop to modern machines. Baumgärtel's story therefore begins, after a short visit to Edison's film loop of a kissing couple from 1896, with Schaeffer's experiments with reel tape in the 40s.

Indeed, Baumgärtel succeeds in bringing the Frenchman to life

Indeed, Baumgärtel succeeds in bringing the Frenchman to life: his ambitions, stubbornness, the rivalry with Stockhausen that has everything to do with the war and not so much to do with their shared interest in studio technique. The German is intent on continuing the serialism interrupted by Nazism, while Schaeffer indulges in surrealism and a utopia of uniting technology and nature.

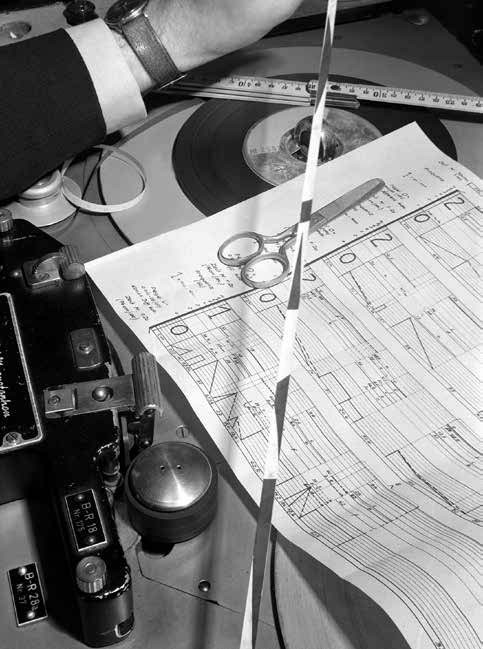

With his short loops, he tries to repeat himself out of the origin of the sound. Manipulates recordings of a train so that in the end – at least that is the ambition – they appear as abstract radio art, a way into the inner soul of things. He compares it to words that have slipped out of the dictionary's straitjacket, a release. But it is also, of course, a way for Schaeffer to control the machine, to tame it with the mechanical precision of the loop.

Stockhausen works differently, although it is Schaeffer who teaches him the technique. He is not interested in the Frenchman's romantic idea of setting the sounds of the world free. No, he will transcend the limitations of the world. Creating new timbres out of laboratory sine tones, putting them together without having to take into account a musician's physics.

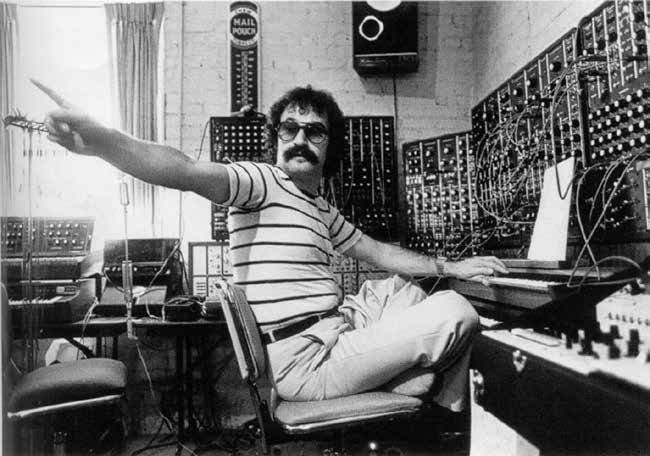

Baumgärtel skewers him. Finds that Stockhausen, in his search for »pure« sound, over which the composer must »master«, does not himself hear whom he is reminding of. Touché. But he also shows very clearly how the infamous composer with his frugal loops of sine tones breaks the sound down to atoms and already in the 50s anticipates the synthesizers of Robert Moog and Don Buchla.

The irony is, as Baumgärtel points out, that both Schaeffer and Stockhausen disavow repetition as a stylistic marker. They are both shaped by a European modernism that relies on linear development and complexity. The loop can perhaps be used on a micro level, but always only as a means of composing works with progressive structures. That's why they are in Now and Forever only precursors to the real heroes of the book.

Thus the pop starts to work just like Schaeffer

Next stop Elvis

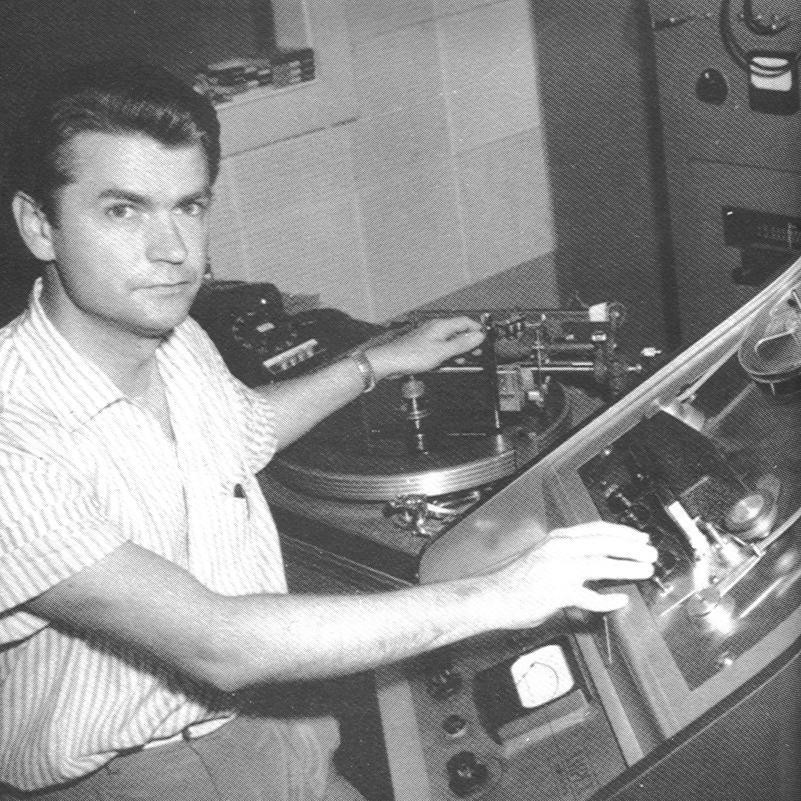

The wonderful thing is that Baumgärtel moves towards these heroes – and yes, of course, they are the minimalists, otherwise I would not have written a thesis about them – by very surprising detours. First, the tour goes to Elvis' first producer, Sam Phillips, who more or less invented the sound of rock'n'roll by adding a slapback echo for the singer's vocals, created with two Ampex tape recorders in 1954 during the recording of »That's All Right, Mama«.

Is it a revolution? To that extent. Phillips' invention becomes the beginning of a popular music genre that was created under the conditions of the studio and cannot necessarily be recreated live. Unlike the Les Paul, which ten years earlier had created a discreet echo with a precursor to the reel-to-reel tape, Phillips puts the manipulation at the center.

Thus the pop starts to work just like Schaeffer. It separates the sound from its source. Elvis' vocals seem inhuman, writes Baumgärtel, it has an eerie quality, »as if the machines had developed a will of their own«. Guitars begin to exceed their own limits, basses sound like percussion, and in the subsequent chapter about sound engineer Raymond Scott, the 70s keyboard player is proclaimed a magician for his use of the Mellotron with its hidden tape loops.

In addition to Scott and his visionary inventions such as the sequencer, Baumgärtel also gets past Peter Roehr's repetitive montage film before the minimalists. On the way there, he draws a portrait of the 60s as a time when repetition is gaining ground across the art forms, because the artists simply let the machines of time run by themselves and listen to their embedded message, their inherited language: repetition.

Turntables, tape recorders, video cameras, synthesizers, sequencers and computers, they are all messengers of repetition. The task of art: to make the machine relatable, to find a crack in its mechanical repetition where man can penetrate and become part of its eternity.

For the art of repetition, it is therefore not about relating either critically or uncritically to a world populated by more and more machines, writes Baumgärtel. It's about listening in a new way.

Just as one declares the author dead and the reader born, music, with its focus on repetition, shifts the formation of meaning from the work to the listener. You hear the same loop over and over again – and suddenly you notice completely new things, disappear into the sound in a way that the composer has no control over.

The loop adjusts itself

This is the phenomenon that minimalism gives birth to. First with La Monte Young's monotonous aesthetics, which the author very creatively contrasts with Andy Warhol's art. The hermit to the pop artist, the furniture-like creature of the drones mirrored in the distance considers Warhol's »cool emptiness«.

Young creates only a few really repetitive works. Brian Eno is quoted in the book as having said of his performance of one of them, [X] for Henry Flynt (1960) that it is the closest musically he has been to an experience of taking drugs.

After a little while you start to hear every type of sound,« he says. »You hear trumpets and bells and people talking clear words. This despite the fact that the work simply consists of repeating a noisy sound, for example a note cluster on a piano, with one or two second intervals x number of times.

Baumgärtel has a keen eye for music's reflections in other arts and culture in general. Warhol's repetitions – films like Sleep or the portraits of celebrities – he calls ambivalent. John Cage sees them as a way of enhancing perception, others see them as social criticism, but Baumgärtel suggests understanding them as the outsider's (Warhol was the son of Eastern European immigrants) defense of coolness, perhaps not as different from the hermit Young as one would think..

After the chapter on Young and Warhol, the author writes about what looks like the story's greatest hero: Terry Riley. Baumgärtel reaches out to Steve Reich several times for not acknowledging clear inspiration from Riley, and Philip Glass apparently doesn't really interest him, so it becomes the originator of In C, who stands as the central figure of repetitive minimalism.

We hear about the experiments with coiled tape that is wrapped around wine bottles at home in the garden to get a little noise from sand and soil. Mescaline Mix (1960-62). On Riley's use of soul as a starting point for early, remix-prototypical works. And about the recognition of the power of repetition during work with Music for The Gift (1963), where he lets the loops take care of themselves, so that they can »become like a Mantra«

With Donna Summer as a cyborg, man is made into a machine

The misunderstood repetition

From there quickly past Reich, who, like Riley, is concerned with creating a loop music piece with roots in American life: the preacher in It’s Gonna Rain, the black teenage snake in Come Out.

On to a separate chapter about the writer Ken Kesey and his wild bus ride with The Merry Pranksters, which Tom Wolfe has described in the Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, included in the book for their delayed echo experiments along the way.

Quick stop at The Beatles, who popularized the loop technique as a formative element on »Tomorrow Never Knows« (1966).

And then to the finish with Donna Summer and Giorgio Moroder's style-creating disco track »I Feel Love« (1977), which in its doubled synth bass is reminiscent of Reich's experiments with phase shifting. But which also sounds like the culmination of the human approach to the machine:

»One might ask whether she is really singing to a lover – or perhaps to the repetitive technology that accompanies her.«

With Summer as a cyborg, man is made into a machine, but with the seasick and practically polyrhythmic synth bass that vibrates between the two speakers, the machine is also made human.

And that is the most important point of the book: that the movement from minimalism to disco to techno culture has shown that it is a misunderstanding, inherited from the Frankfurt School, that mechanical repetition is the domain of the death drive and not of liberation.

Eros has recaptured repetition from Thanatos, because by creating a music that puts perception at the center – compare Baumgärtel's inclusion of Merleau-Ponty's phenomenology and Friedrich Perls' gestalt therapy – we can see that music in practice is not so homogeneous and simple, which Adorno warned against.

Whether you disappear into the mosquito light of minimalism and hear a whole personal universe unfold, or create your own liberating beat while dancing under a mirror ball, it is proof of the overwhelming potential of repetition.

Perhaps even as a protection against a world that has long since ceased to look like a place that necessarily develops for the better: »The loop unites, mediates and rebalances,« writes Baumgärtel. It makes the noise of the modern world bearable.

Tilman Baumgärtel: »Now and Forever: Towards a Theory and History of the Loop«. Zer0 Books, 2023, 391 pages.

English translation: Andreo Michaelo Mielczarek