Klang i Tivoli

»Real music is made up of three elements: melody, rhythm and harmony«. Niels Rønsholdt recited those words in a slow, pompous voice as his new piece Civilizations – heard for the first time at Klang Festival’s Tivoli concert on Tuesday – argued the opposite.

Rønsholdt was in good company. Athelas Sinfonietta opened with György Ligeti’s Ramifications, a short piece that does its thing with no recourse to melody whatsoever. Except, that’s not quite true. In the end, Ramifications’ process of slowly dismembering its own polyphonic weave does produce little glimpses of melody. Instrumental tendrils suddenly find themselves un-plaited, free to roam onto melodic ground.

That, surely, is a side effect of Ligeti’s experiment rather than an objective. This composer as much as any disproves the parochial edict that Rønsholdt’s piece set out to ridicule, even if Ramifications throws it a bone in the end. But so pure and subtle was Athelas’s performance under Pierre-André Valade – so ‘distant’ even – that Ligeti’s little melodic foray was easy to miss. We didn’t get a forensic picture of Ligeti’s untangling and re-tangling string voices in this performance, but we got a landscape of hovering beauty as the pay-off. Worth it? On balance it probably was.

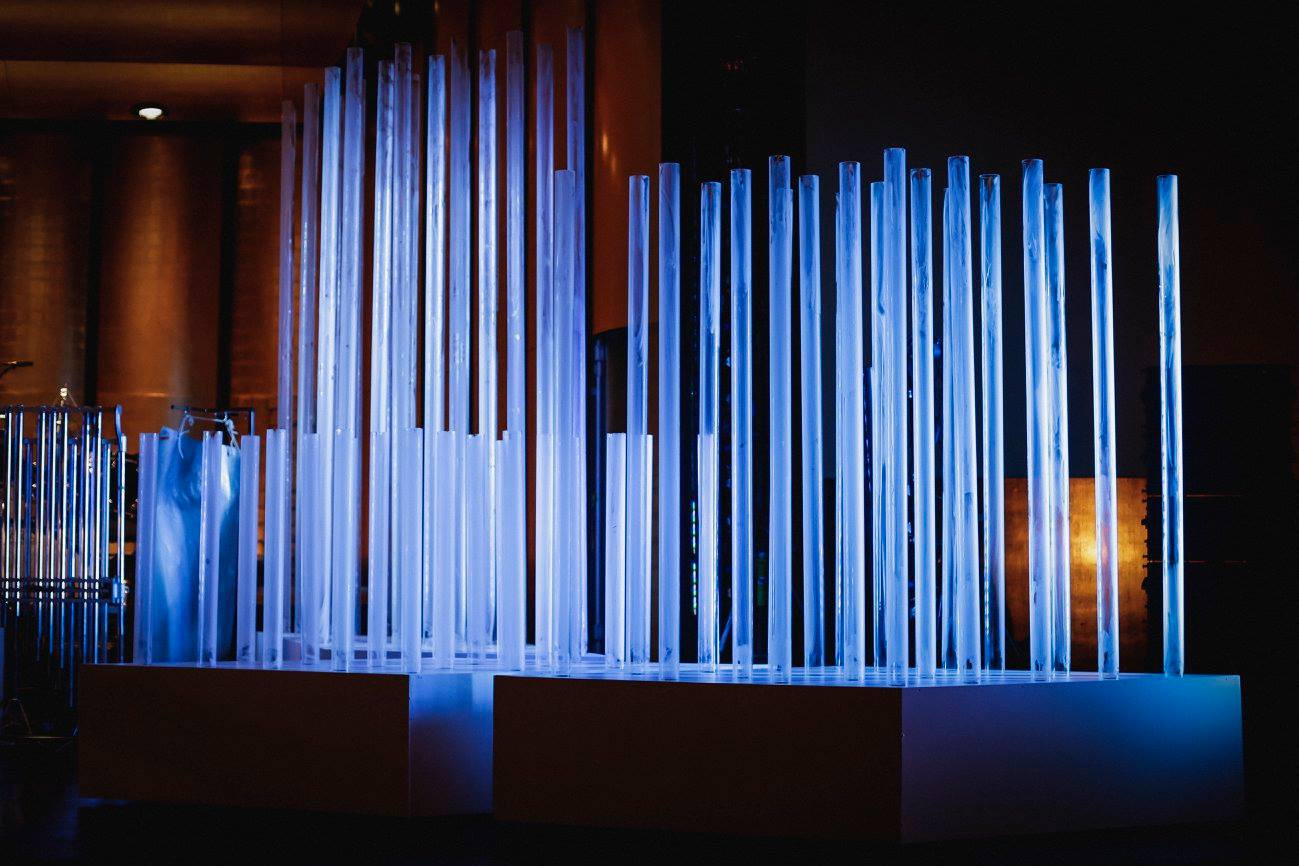

Overview of the stage with both orchestra and the Greenlandic Aavaat Koret. Foto: Dennis Lehmann

Overview of the stage with both orchestra and the Greenlandic Aavaat Koret. Foto: Dennis Lehmann

But is it appropriate to view Ligeti’s work with theoretic as well as aesthetic distance? Rønsholdt’s piece suggested that Ligeti’s arguments from 1969 are still in need of voicing. Of course, the composer started to get suspicious of equal temperament soon thereafter, playing around with microtones. He was already doing it at the time of Ramifications, as was Per Nørgård, whose Voyage Into the Golden Screen was written at exactly the same time.

There are a few ‘firsts’ going on in Nørgård’s piece. Its second movement contains the first instance of the composer employing his infinity series in a multilayered, fractal context. Nørgård has also described it as »the first work in which I leave the forming of the music to the listeners.« You could say both those qualities are intertwined. If the conductor tries to shape the music’s interlocking gestures too much, the base pattern – that which allows the formation of the music in the the mind – will disintegrate. Within that, any performance needs to carefully handle the central Nørgård conceit that instruments aren’t so much in counterpoint with one another as inducing speech in one another – birthing each other’s notes.

Conductor Valade and Athelas’s ability to sustain the music without shaping it, not so easy in a piece like this, which shows its workings so clearly with vibrato-less strings at the forefront, was mightily impressive. As was the natural, bending feel of the microtonal tuning, particularly from the low brass. But it felt rather like the piece was being presented to us finished, decided, cleaned-up – not in the ‘over to you’ terms described by the composer. Perhaps that’s what time and technical advancement does to a score born when these ideas were so new, on paper at least.

Raus

And so to the actually new, which arrived first, after the interval, in the form of Raus by James Black. On one level, the piece felt like a rebuttal of Rønsholdt’s ‘real music’ definition but on entirely different terms to those of Ligeti and Nørgård: it didn’t prove its point by removing one element from the equation, it simply presented melody, rhythm and harmony individually – unrelated but often at the same time. Any idiot can throw melody, rhythm and harmony into a pot, but the result isn’t necessarily the sort of music that Rønsholdt’s nostalgic alter ego thinks is ‘real’.

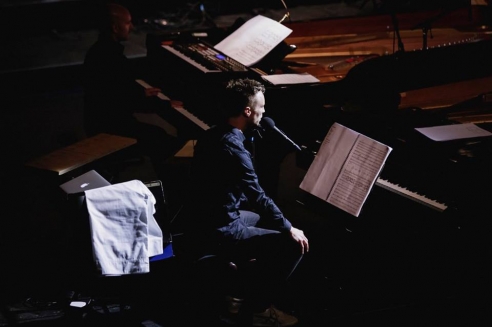

James Black on stage in Tivoli. Foto: Dennis Lehmann

James Black on stage in Tivoli. Foto: Dennis Lehmann

So, Black began with a melody – a folk ditty sung by himself and the Athelas instrumentalists while the pianist whipped-up the strings of the piano with his hands. Next, Black launched into a sort of oral-manual collage, spouting noises and half-words each of which bore an equivalent hand signal. Soon the noises disappeared but the hand-signals continued, like a silent ritual reflecting some long-lost digital memory.

There were elements of noise music to Raus, shunted-up against the purity and innocence of schoolroom recorders, honest folksong and the directionless mania of computer-game music. But Black surely had one eye on how the whole thing looked as well as an ear on how it sounded. He stood behind what looked to the untrained eye like a Casio keyboard, wearing a white tuxedo; behind him, Jesper Garde Kongshaug’s lighting designs shimmied away in greens and reds. In a concert of avant-garde music, it felt for a moment as though Tivoli was getting its taste of the working men’s clubs of northern England.

Niels Rønsholdt is never usually afraid of laying himself bare on stage, nor of challenging his audience into pitching-in with something more than an aesthetic judgment call. Civilizations does the latter very obviously indeed. But the message in the score is strong enough to mean the one theatrical element of the piece ends up seeming pretty tame, not least as you can see it coming a mile off.

Niels Rønsholdt. Foto: Dennis Lehmann

Niels Rønsholdt. Foto: Dennis Lehmann

Rønsholdt’s faux-recitation of a ludicrously small-minded manifesto for ‘real music’ has resonance in an age when politicians are trying to kick-start a neo-nationalistic cultural project, apparently unaware that any artist of merit is compelled never to think along the same lines as they do. But the uncomfortable truth sits rather closer to home: there are many in the musical community who would nod in quiet agreement with the text Rønsholdt reads as part of Civilizations, and our collective lack of regard for world ‘musics’ with their own parameters of exploration that might display limited interest in melody, rhythm and harmony proves as much.

Rønsholdt’s piece literally forced its mantra that music must contain all three onto a group of singers with their own tradition that doesn’t necessarily agree. Singers from the Greenlandic Aavaat Koret had their music ‘completed’ by the piece – in other words, harmonized in the European tradition, thank you very much.

Underneath, Rønsholdt’s ensemble was all heavy, enforced, emblazoned chords, impassioned rhapsody and schizoid gestures on the piano. Eventually, Rønsholdt decked himself out in one of Aavaat Koret’s white tunics – which was there, draped over a music stand next to him all along – and moved from the front of the stage around to the back, to join the choir who were now chanting on a unison. Point made. Like a lot of Rønsholdt’s work, the whole thing could feel like a giant abstraction. Until, that is, a percussionist at the back went ballistic on his drum kit. Ah, thank heaven...some real music at last.