Who said that simplicity should be simple?

When pianist Nikolaus von Bemberg made his debut last year at the Royal Danish Academy of Music, several surprising things happened during his graduation concert.

One was that his colleague James Black – the leader of Klang Festival and also a composer used to experimenting with different media – suddenly appeared on video as a murder victim in a satire of Nordic crime series. Another, more sensitive surprise came from actor Bless Amada, who, while chaotic sine tones seeped through in von Bemberg’s own work A Day in the Life (2024), portrayed stress in a way that many could probably relate to.

Not only did he sit down and read Rilke on stage, but he also started playing a vinyl record

Since then I have been thinking about what Amada did when the anxiety and mental turmoil set in. Not only did he sit down and read Rilke on stage, but he also started playing a vinyl record: the now 71-year-old Swiss composer Jürg Frey’s 4th string quartet (2018-20), which had been released a few months earlier in a recording by the Canadian Quatuor Bozzini.

It is a work and a composer for whom simplicity plays an absolutely central role. Frey is known as the most prominent member of the musical silence collective Wandelweiser, which has for over 30 years carried the legacy of figures like John Cage and Morton Feldman into the present, with music that seeks pauses and quietness. What made the album one of the finest of 2024 was that, with Bozzini’s delicate performance, you could hear an unexpected life in an otherwise rather mechanical music. The simplicity took on a depth that reminded one of life itself.

In recent weeks, several events have made me think about the peace that Frey’s string quartet helped manifest in Nikolaus von Bemberg’s work, which ended with birdsong and images of a peaceful coastal landscape. First, I discovered that Bozzini re-released their previously unavailable Frey album String Quartets from 2006, which contains four works composed between 1988 and 2000, including the significant 2nd string quartet, where Frey, with a special trembling half-tone technique, makes the strings quiver like a distant ghost choir. It was, in itself, a reflection on the potential of simplicity today.

»I tend to think of silence as a kind of material. It’s like a square in a city«

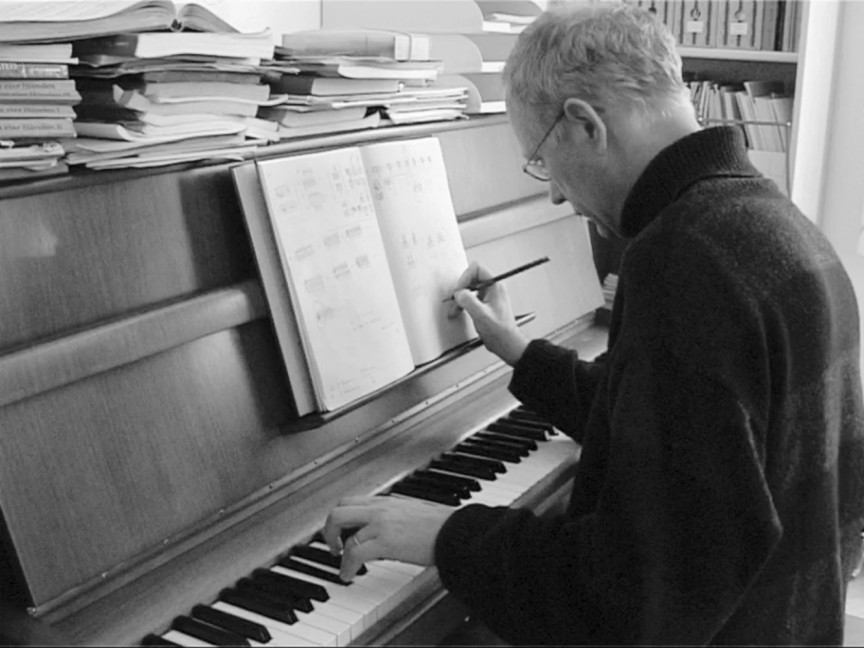

Then, I discovered that 53-year-old Simon Christensen, another contemporary composer with great respect for conceptual string quartets, had new work ready. His 45-minute long string quartet EKSTASIS – Polyphōnos discordiae, recorded by the Polish NeoQuartet, also seeks simplicity, but a different, perhaps more iconoclastic kind than Frey’s.

Finally, 45-year-old Anders Lauge Meldgaard, together with the string ensemble Halvcirkel, released Spirit, an album based on the idea that Meldgaard replaces a missing violin – Halvcirkel was previously a quartet but is now a trio – with a Japanese version of the proto-synthesizer ondes Martenot. His music is also shaped by simplicity, but, voila, in a completely different – perhaps utopian – sense.

It’s like hearing the chorus to your own funeral – from inside the coffin

The Architecture of Silence

The strange thing about Jürg Frey, as mentioned in an interview with The New Yorker from 2019, is that the Swiss composer simultaneously appears both as an avant-gardist and a romantic. Rebel and elegant. Like his fellow members of the Wandelweiser group, he, in the tradition of John Cage’s 4'33", is focused on silence, but while Cage was particularly interested in what silence could say about the social context of music, Frey is just as concerned with the formal potential of silence:

»I tend to think of silence as a kind of material,« he says in the interview. »It’s like a square in a city. The square can be empty, but it’s defined by the buildings around it, and the buildings are defined by it. Silence becomes part of the form. That’s what I take with me from the whole Wandelweiser experience. I’m very interested in form and the energies that come from form.«

That’s the talk of a stylist. But in the accompanying text to Quatuor Bozzini’s re-release of Frey’s early string quartet works, they are described as radical, »a challenge that has to be accepted,« and having had a profound influence on the Canadians’ approach to performing new music – including Niels Lyhne Løkkegaard’s fine Colliding Bubbles, which they released last year.

Listening to the early quartets, it’s clear there is a more stringent composer at work than in the 4th, where Bless Amada found peace. The slightly dissonant and circling opening of the just over ten-minute-long 1st string quartet from 1988 sounds as if the musicians are tugging at something. Slowly, however, the motif becomes purer, more delicate, hissing – beautiful – before Frey breaks it down into a kind of basic syntax of bowing and snapping: lines and dots in a musical grammar, the language cut down to its core. What began as a completely natural, obligatory movement ends up as something meaningless. It resembles a postmodern argument that meaning is not something that exists but something we create.

Here, simplicity rests in itself, it is romantic, stylistic, and, for better or worse, good taste. Is it also... rigid?

Death Knocks

Frey is even stricter in the double-length (Untitled) VI from 1990-91. Here, he starts with a repeated major scale that ends a half-tone too high, and it is not until five minutes in that the quartet lands its first harmony, but the solitary search soon returns before it finally, more than halfway through the piece, suggests company: a light tone that sticks to the sky like a guiding star, but fades away; the music, which eventually lands gently on a cloud like a softly ringing life.

The simplicity sounds, for long stretches, like a manifesto – but in that case, a manifesto for sensitivity – a way out of rigid systems and into sensitivity. It is this path that Frey truly embarks upon with the 2nd string quartet from 1998-2000, which now lasts nearly half an hour. Its radicalism, however, is quite real; here, the strings’ distant, hazy minor chords are buried in the mix alongside the hissing and rumbling; it’s like hearing the chorus to your own funeral – from inside the coffin.

With its radical simplicity, Frey shows us Death here: all and nothing at the same time

Here, we are too far away to hear the strokes that, with Bozzini’s ultra-fine touch, made the music come alive despite strict patterns in the earlier quartets. We only hear the tone and the wail, conveyed with Frey’s unique half-tone technique: One finger defines the pitch while another finger lightly touches the string, forcing a noisy tone that sounds like two half-tones on one string.

Stretched over half an hour, it becomes a radicalization of 90’s new-age music, but at the same time, we are also outside of time, humanity, tones, and instruments: What is the story – about the world, classical music, the string quartet as a genre – that here returns as a catatonic procession of ghosts? With its radical simplicity, Frey shows us Death here: all and nothing at the same time.

In comparison, the 4th string quartet, which lasts just over an hour, is more sentimental and structurally varied with clear shifts between major and minor, distinct motifs – Morse rhythm, ambulance sirens – and a long mourning movement as the ending. Here, simplicity rests in itself, it is romantic, stylistic, and, for better or worse, good taste. Is it also... rigid?

The Quartet as a Weapon

Nine years ago, Simon Christensen – a classically trained composer, but also a performing organist, drummer, and electronic musician – released a rather extreme string quartet, recorded by an ad hoc ensemble consisting of Signe Madsen, Birgitte Bærentzen Phil, Mina Fred, and Sofia Olsson. MANIFEST – But There’s No Need to Shout (2012-13) lasted five quarters, but developed almost not at all. Instead, it was a swaying marathon where loose strings rang like a foghorn with only brief pauses: a meditation on a geological timescale.

The barking staccato sounds like a puppy trying to get out of a hole

Earlier, Christensen had explored a folk-music core in Towards Nothingness from 2008, a roughly ten-minute string quartet with a coarse, deep organ pedal where the music slowly eroded. And also in the later, similarly long The Whistle Quartet from 2018, where tough, arrhythmic strings were joined by agitated referee whistles, the focus was on breakdowns. All three works resembled confrontations with the string quartet as the classical music's most prestigious format – a movement away from the stylized and into something primitive but genuine.

On Christensen’s new album, the Polish NeoQuartet performs his EKSTASIS – Polyphōnos discordiae (2019-20), whose title refers to ecstasy, the polyphonic, and the oppositions that meet. Several strings are tuned a little lower, so dissonance becomes the music’s natural resting point, and the beginning of the piece sounds exactly like an orchestra trying to tune, but unable. The notation, however, is hyper-complex, and gradually, the strokes become clearer, so you really hear the materiality of the strings when the bows tear into them; the barking staccato sounds like a puppy trying to get out of a hole.

The interesting thing, however, is that Simon Christensen, in this three-quarter-hour work, seeks intimacy. Soft hissing and pauses appear, as the quartet slowly but steadily dissolves itself before, halfway through, re-emerging as a working organism: In the middle of what the album calls the third movement, a gnawing repetition begins, as if they are digging a hole, led by deep, rough shoveling in the cello. In the high end of the register, the strings ring like a crisp, loose sitar, and at intervals, the workers take whispering breaks before continuing. Here, you almost hear classical layers being peeled away in favor of other cultures' sonic ideals and percussive drift, before the movement finally finds peace in a porous passage with vibrato: something strange coming out of the breakdown.

From there, Christensen seeks to redefine the potential of the string quartet as a format. At one point, the music shrinks down to a single string and knocks on the instruments, and later, he finds strange sounds: from the reminiscence of a wet, bubbling spring and a dry nail file, to something spirit-like with a glass tube sliding on the cello. Finally, the work tunes in and out of minor in an elevated, sorrowful ending – a kind of reconciliation with the format, but on simplicity’s terms.

Casper the friendly ghost joins Meldgaard’s already happy-go-lucky sunny universe

Off to the Island of Desire

If simplicity in Jürg Frey communicates a sensitivity that doesn’t oppose the tradition of classical music, but actually nurtures the elegant structure, while simplicity in Simon Christensen insists on being a potential weapon against good taste, then something entirely different is at play in Anders Lauge Meldgaard’s approach to the simple.

His and Halvcirkel’s Spirit builds somewhat on their Fragment 94 from 2021, where Mette Moestrup read Sappho fragments with so much space between the words that you had to write them down to understand the meaning. In this way, the darker elements in phrases like »I’d rather be dead« weren’t just contrasted, but dominated by a bubbly light music full of major chords and happy neobaroque. It was almost – like much of Meldgaard’s music – a manifesto for the light.

On the new album, however, one of the violins has been replaced by the Japanese Ondomo keyboard – a newer and more portable version of the ondes Martenot, invented by Frenchman Maurice Martenot in 1928, the same year that Russian Leon Theremin patented the sonically similar theremin. This substitution adds something extra playful, cute, and foreign to the music: Casper the friendly ghost joins Meldgaard’s already happy-go-lucky sunny universe.

What’s incredible about his music – including the eight works on Spirit – is that it manages to stay fresh even though it rarely works with contrasts to the paradisiacal. There are references to American 60s minimalism, such as when Song of the Meadow in Bloom makes rhythmic and harmonic leaps like Philip Glass, when Fragment 94 Revisited phase-shifts snaps like Steve Reich, or when the closing Reprise works with Terry Riley-inspired echo and something that resembles backward sound. But there are also passages that sound like ASMR – not least the creaks, rubs, and pop sounds on Sparkle – or, with simple melodies, like Nintendo music.

The world is complex – so complex that even simplicity is

Even when, as in the title piece, there are persistent noise sounds, they are treated with care, as if they were a sweet, crackling budgie. Immediately, the strings lay down a conciliatory harmonic foundation, just as the chaos, which threatens with the shifts in Fragment 94 Revisited, never develops into anything dangerous. Still, the slimness in the expression ensures the interest is sustained. The light siren that breaks out in the Sappho fragment For Only You Know How Much I Enjoyed You shines irresistibly with the Ondomo tone surrounded by shadow movements and tremolo.

Whether this expresses escapism or utopia is open for discussion. In any case, it stands in sharp contrast to Frey’s death-like 2nd string quartet, perhaps with a touch of Peter Pan syndrome: the celebration of the childish, of naivety as an ideal. A contagious ideal, if so. Each thing in its time, each simplicity with its purpose. The world is complex – so complex that even simplicity is.

Simon Christensen’s »EKSTASIS« was released on February 21st on Dacapo, Jürg Frey’s »String Quartets« was re-released on March 7th on Collection QB, and Anders Lauge Meldgaard and Halvcirkel’s »Spirit« was released on March 15th on År & Dag.

English translation: Andreo Michaelo Mielczarek. Proofreadling: Seb Doubinsky