Shoes For People Who Don’t Like Music

My first lesson in music theory occurred in my early teens while listening to a cheap transistor radio under the blankets when I should have been going to sleep. On air was a Top 40 AM station, an odd eclecticism where psychedelic music followed singing nuns, while new hits rocketed to the top of the charts and others headed for landfill.

It was all fascinating, but something was troubling me, in a homegrown existentialist way

The business model was to sell my attention to the advertisers and whatever the advertisers were selling to me, yet I took no notice because in the United States everything is on sale all the time. The DJ who pretended to be everyone's best friend used songs and jingles to fish with hooks and earworms. It was all fascinating, but something was troubling me, in a homegrown existentialist way. Given that all the music drew from a finite set of notes, it was obvious that the limit of possible combinations would soon be reached, all available melodies would be exhausted, and there would be no new songs, nothing to rotate. Stations would become stuck on automatic replay, over and over again, grinding reality down into the Eternal Return of a musical cosmos that had already happened many times before. I fell asleep before becoming too despondent.

I didn't know what Surrealism was, so I began schooling myself on its art and literature

Around the same time, my twin brother and I received gift certificates to the local record shop for our birthday. Our parents had a hi-fi console and easy listening, musicals, a comedy record, and at least one Leonard Bernstein, which we'd effectively committed to memory. We bought our own LPs for the first time. My very first LP was Surrealistic Pillow by Jefferson Airplane. I didn't know what Surrealism was, so I began schooling myself on its art and literature. Each book I opened contained sentences requiring other books. It eventually became clear that the lightning-filled nights of the unconscious illuminating dreams into their own wakefulness in André Breton's 1924 Manifesto of Surrealism was the Pillow part of the Airplane. In retrospect, whoever gave us the gift certificate was the Pusher Man in a bad drug warning movie, The first one's free, kid. There would be years when my habit was so heavy more money went to LPs and books than rent and food.

My brother's fatalism, on the other hand, disclosed itself immediately. Three or four LPs deep into the gift certificate and he came home with an Andy Williams record, a deep-50s non-descript crooner our parents listened to. I asked him why and he said, »I don't like it now, but I figure I will when I grow up.« That was too funny to be sad. Usually, whiskey and mushrooms pair better with knowing you will like something you dislike now. Fatalism is at work in how a flashing combination of hormones and life events of people in their teens can chart out their musical predilections for a lifetime, the same way the positions of the planets astrologically puppet people from the time of their birth. My solar system is filled with asteroid belts and lost satellites.

I have never been attracted to music where I know what will happen next

Music I can’t believe in

I'm not sure which hormones or biochemistries, psychotropics, or life events are responsible, but I have never been attracted to music where I know what will happen next. This means I can't listen to too much Bach because I will soon see what's coming. Alvin Lucier's North American Time Capsule (1967) is one of my favorites, but I don't play it often for fear I might start tapping my feet. Mostly it means that I hear anthems everywhere. During fevered dreams I harbor images of casino tribute bands in powder blue blazers performing to rows of pinkish beige, rolled-and-tucked furniture on which people my own age are planted.

One of the saddest things I've ever seen was a floor of slot machines so vast the curvature of the earth was visible. Flashing colored lights dappled the surfaces of people already laid waste, some towing tanks of emphysema oxygen feeding the tubes in their nose. The sound was an ocean of ambient music, itself hovering like a smog in a copyrighted din of sound effects, punctuated by the pounding of illuminated buttons on the slots. The United States is filled with marketed sad fate. More than my music theory has been formed in opposition to such assisted suicide.

The radio station broadcasted from Seattle, and it was where we received our other fashion cues

Seattle was a ferry ride from our small town. The radio station broadcasted from Seattle, and it was where we received our other fashion cues. Walking downtown one day I witnessed two people arguing about shoes displayed in a shop window. They were discussing in great detail the pros and cons of what looked to me like two pairs of the exact same wingtips. Once they left, I moved closer and saw that they were effectively the same exact shoe, both pairs made by Bateson, the only difference being the pattern of holes inscribed. One curled in while the other curled out, something like that, it shouldn't matter. Wingtip music is everywhere.

The Surrealists did not have much to do with music and, in fact, they tinkered with outright antagonism. Not stopping at the dead donkeys wedged under the lids of two grand pianos, or the befuddled priests in tow, in Un Chien Andalou (1929), Salvador Dalí and Luis Buñuel cut back the lips to pun the donkey teeth with piano keys, just as the thin cloud had been taken to the woman's eye of a moonlit night. The burden of the protagonist is to tow the pianos, donkeys and priests out of the room, ostensibly to declutter. The next antagonism would have been to perform a serenade on the two sets of keys.

The idea that anyone could be antagonistic to music per se is odd. Someone should have told that to Boston's resident rock critic at the Static and Interference: The Cultural Politics of Alternative Music (1988) event at the Institute for Contemporary Art. I was one of the invited speakers. It was an assorted gathering of the art world, academia, musicians, and an audience that was younger than normal, some of them sitting with the skateboards they drove in on. A well-known cultural studies professor who had more money in his suit than most people in the audience saw in a month, reworked the notion of Antonio Gramsci's hegemony to persuade them to be less noisy and alternative and be more like the Pet Shop Boys, apparently because that was where revolutionary change was really taking place.

The rock critic in the front row was clearly not happy with what I was saying

He read his paper but had not read the room. I forget what I talked about, probably not much different in character to what I am saying here, tangents from everywhere that threaten to weave together somewhere. The rock critic in the front row was clearly not happy with what I was saying. It is not that difficult to read faces, especially those of people who also hold their hearts or other internal organs on their sleeves. He demonstrated enough self-restraint not to interrupt but, once I stopped, he stood up, turned to the audience and gestured backhandedly to me, waving me off with »Why is he speaking here? He doesn't even like music!« The audience was alternative enough to find it funny too.

The poetry of atoms and music’s resistance

Another feature of the Surrealists was how they ran against the grain of abstraction that had taken hold of other movements in the first third of the twentieth century. It is easy to see how the two – little concern for music and abstraction – are related to the stripped-down sounds that are tones and notes, the atoms of much music. They were not entranced by science and mathematics either. They didn't know what they were missing. As a mathematics major when I began university, I found thinking about n-dimensions, perhaps thinking in n-dimensions, entirely amenable to dream states and intuition that the Surrealists pillowed. In this equation, let wingtip holes be absented atoms and allow particles of dust in the air, ignoring gravity, to function within what Gaston Bachelard called an atomistic intuition.

Physics can be quite stylish, but the floor of quantum behavior is so thin that dancing should proceed with caution

...as long as a reflected and diffuse light fills the room with a uniform clarity, the room is empty, the dust is invisible. Let a sharp, straight ray appear and immediately this ray of light reveals an unknown world... From now on, in fact, we can recognize our right to postulate matter beyond sensation since, in a way, experience has shown us the invisible. So we postulate the atom of matter beyond the experience of the senses. We are ready to speak of the atom of smell, of sound, and of light since we have just seen, in an auspicious and exceptional experience, the intangible atom of touch.

Too much atomistic intuitional dust in the room makes it difficult to breath, of course. It happens when, in Isabelle Stengers words, physics anoints itself the »noble activity of meaning creation«, one that presumes to rule the roost when at times it is better used as a feather duster. Physics can be quite stylish, but the floor of quantum behavior is so thin that dancing should proceed with caution, and earwormholes are not that catchy, if you get sucked in.

Not everything is amenable to laboratory precision. The Russian Yevgeny Zamyatin wrote as much in his dystopian novel We (1920) where Platonic ideals and Guardians are in full control mode and the measure of music has become measure.

...I switched my attention back on only when the phonolecturer had gone on to the main theme: to our music, to mathematical composition (the mathematician is the cause, the music is the result), to a description of the recently invented musicometer. »By simply turning this handle, anyone of you can produce up to three sonatas in an hour. Yet how difficult that was for your ancestors to achieve. They could create only by driving themselves into fits of inspiration – an unknown form of epilepsy.

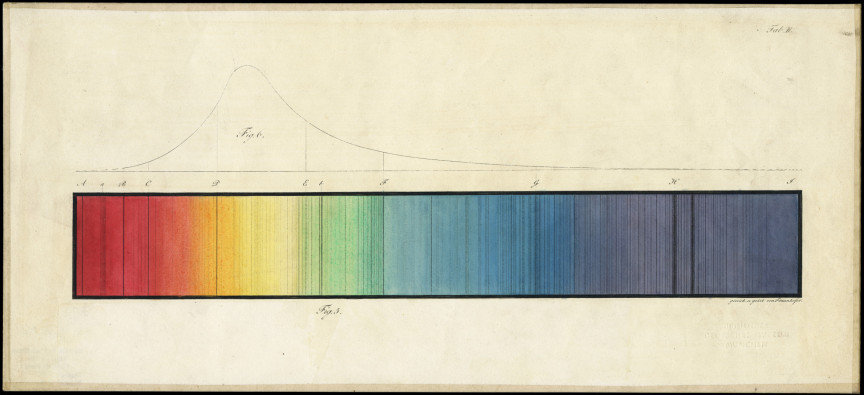

...With what pleasure I listened to our contemporary music afterwards... The crystalline chromatic progressions of merging and diverging series – and the summarizing chords of Taylor Maclauren; the full-bodied/full-toned, squarely massive passages of the Pythagorean theorem; the mournful melodies of a fading oscillatory movement; the brilliant measures alternating with Fraunhofer's lines in the pauses – the spectral analysis of the planets... What grandeur! What unwavering equilibrium. And how pitiful – totally unrestricted by anything other than wild fantasies – that willful music of the ancients...

I drove nearly three hours to see John Cage

To tell the truth, I wouldn't mind listening to Fraunhofer lines. I think Zamyatin may have made a mistake. The continuous color gradation of the visible light spectrum is better in step with the Pythagorean orderliness he was satirizing, but what better way to interrupt the full-Sun, high-noon knowledge of Platonic illumination than with the herky-jerky off-kilter raggedness of Fraunhofer lines? Terry Riley's A Rainbow in Curved Air could use a few.

A moment of silence before the explosion

I have gone to great lengths to not know what would happen next. I drove nearly three hours to see John Cage, the person known best for being in control of relinquishing control of what happens next. He never ceded control the way a person possessed would which, in music, might intersect with certain forms of ritual and improvisation, but are very different from situations outside music where people are dangerously out of control. Even when raucous, Cage's work is genteel. Only within the gravitational orbit of a symphony orchestra, one of the most obedient bodies in the universe, would submitting holes to chance seem like ceding control.

He was performing Mureau and for that reason it was difficult to find anyone to go with me. A three-hour drive and another three back to see some old guy on stage reciting nonsense didn't have »date night« written all over it. They were the unfortunate ones. I didn't know what would happen, but they didn't know what they were missing. Mureau was formed from passages of Henry David Thoreau's written mentions of music (music + Thoreau = Mureau) that were then subjected to Cagean procedures. The richness of Thoreau's writing helped quite a bit, and I imagine Cage made good use of a Thoreau concordance, a search tool of its day. Cage was an ingredients chef. No fancy spice combinations, no exact measurements, or complicated stages of preparation, merely chop up what is already high quality and serve raw.

Sleeping in concerts should be encouraged

The performance was long, and Cage's mellifluous voice was undramatic and soporific. I fell asleep, twice. Going to sleep may seem like a sign of disinterest or one way to leave a boring performance. Far from it. Dick Higgins wrote about productive boredom in »Boredom and Danger«. The test case for him was a 25-hour performance of Erik Satie's Vexations (32 bars repeated 840 times). Was it boring? »Only at first. After a while [euphoria] begins to intensify. By the time the piece is over, the silence is absolutely numbing, so much of an environment has the piece become.« Cage was cooking with Thoreau and I was a dream chef cooking with Mureau. In what other circumstances could I fade into and out of hypnagogia, waking up afresh to the voice of Cage speaking disjointed sentences from a lone chair? Twice? No one can compose that. Besides, the naps helped me stay awake in the early hours of the morning during the long drive back. Thankfully, it was Mureau and not Vexations. On the road after 25 hours, I could have killed somebody.

I don't know if I snored during the performance. It's an old joke, »I stayed up one whole night to see if I snored...« It shouldn't have mattered given the tolerance of Cagean decorum. Sleeping in concerts should be encouraged. There is nothing mean-spirited about sleeping, and waking up could renew the classics.

He was an incredibly generous person, so sharing the flu was in character

During the performance of a long, quiet Morton Feldman piano piece at The Cage at Wesleyan festival in 1988, the French philosopher and musicologist, Daniel Charles, fell asleep. This was a week-long festival celebrating Cage on his 75th birthday, who arrived with a mild flu and by the end of the festival most people had come down with the Cage flu. He was an incredibly generous person, so sharing the flu was in character.

Most people at the festival would have known Charles for his book, For the Birds: John Cage in Conversation with Daniel Charles, a standard for anyone interested in Cage. By the time the Morton Feldman concert rolled around, people knew him more personally and had grown familiar with his friendliness and humor. Being a grand piano of a man, his snoring swept up through infrasound to resonantly thunder out the actual piano. A sea of necks turned from the pianist and swept toward the source, people smiled at each other, and someone gave him a nudge. Perhaps if it were a Cage rather than Feldman piece, the nudge would have been withheld like Tudor not touching the keys in the Woodstock premier of 4'33". Program notes, however, would pose a problem: »this evening's snorist is....«

When Cage wrote »For More New Sounds« in 1942 it is unlikely he had »snoring philosopher« in the back of his mind. When I asked James Tenney about where he placed himself in the Varèse and Cage legacy of all sounds being available to music, fodder for the new in new music, whether there were any sounds left to be new, and whether it was possible to still make claims to liberation, freedom, etc., he explained:

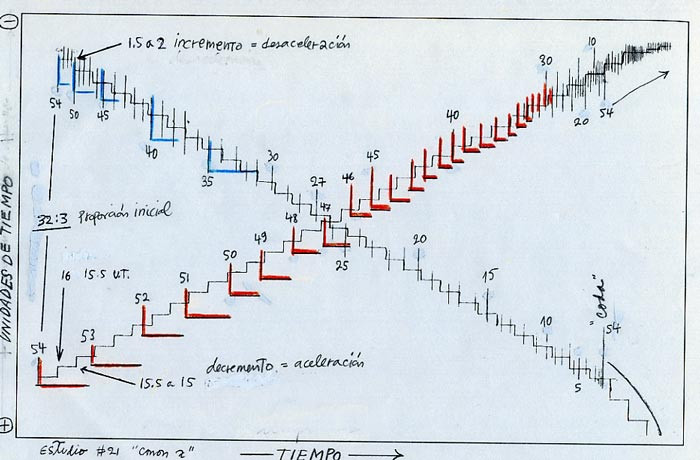

Sure, there's a kind of aesthetic liberation, but I felt that I was simply starting from a place that those composers had already brought us... Yeah, it's liberating, but conceptually it had already been achieved. So, it was just a matter of furthering it. I could carry it further because they didn't have the means, the medium in which this could be realized quite so thoroughly... What the computer did with the program was to make available for the first time in history, the possibility of moving continuously throughout the total field of sound because it was dealing with the signal itself.

The computer-punched cards he used at Bell Labs were an updated version of the piano rolls of Conlon Nancarrow (Tenney sought him out in Mexico). The holes in punched cards and piano rolls are where music and wingtips meet. The proto-computer music of Paul Hindemith's mechanical organ composition for Oskar Schlemmer's Triadisches Ballet and Nancarrow's Study No. 48 really smoke the rolls for me. I was lucky enough to first hear the latter with Nancarrow himself present in the room. The music no doubt sounded different knowing that he traveled to Spain to fight the fascists, and it is still easier to listen to Nancarrow on repeat than Bach.

However, instead of liberating anyone, it is quite possible that modernist plenitude has always existed to provide a soundtrack for Mammon's Maw. For more new must have sounded appetizing in 1942 for stocking the shelves after the starvation of the Great Depression. World war may have been distracting. What goes unnoted, however, is the wake of waste of so much newness, the Great Acceleration, the 1950 hockey-stick downbeat of the current ecological catastrophe.

It is still easier to listen to Nancarrow on repeat than Bach

The residue of holes had drifted into a terraforming scale. What of computational means now? Are the casino slots bots playing themselves yet? I suspect there are already sonifications of cryptocurrency trading providing ambient music for server farms bending over the horizon. Whence music theory? Is there a Schenker to analyze the constant drippenmusik of the Welt Melt? Clearly, teenage angst about the future of music is amateurish when pitted against the future of the future.

There are always means of furthering Tenney's furthering it further, as long as there is something next. One way would be to torque attention toward the signal, that little atom of energy and information he relied upon, the one capable of morphing constellated parameters into and through one another like an n-dimensional sea of Klein bottles. Let's see that on a pair of shoes. It would be very much in line since Cage's for more new sounds already had the subtext for more new signals and Tenney himself once theorized a generalized signal and total transducer that could have gone off in innumerable directions, not just computational and not necessarily music. Meanwhile, I'm bingeing on sarangi.

Sources

Gaston Bachelard, »The Metaphysics of Dust«, in Atomistic Intuitions: An Essay on Classification (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2018).

Isabelle Stengers, Cosmopolitics I, trans. Robert Bononno (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010).

Yevgeny Zamyatin, »We«, in Russian Literature of the 1920s: An Anthology, ed. Carl R. Proffer et al. (Ann Arbor: Ardis, 1987).

Dick Higgins, »Boredom and Danger,« The Something Else Newsletter 1, no. 9 (December 1968).

Douglas Kahn, »For More New Signals«, in Earth Sound Earth Signal: Energies and Earth Magnitude in the Arts (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013).

Douglas Kahn, »James Tenney at Bell Labs«, Leonardo Electronic Almanac 8, no. 11 (February 2001).