2024: An Earful of Chaos

Andreo:

Jennifer, at this year's Venice Biennial war, refugees, and destruction were inescapable. Has the biennial ever been this filled with sound? The experience felt all-encompassing – I heard wrenching, unfamiliar sounds everywhere. Even Björk sailed into Venice to give a secret DJ set in a palazzo.

All the chaos there felt right for a year that has been an annus horribilis. Do chaotic times call for chaotic music – has any been on your mind this year?

Maybe my most chaotic record moment of all for me, though, was last week at my friends’ apartment

Jennifer:

Wide-ranging horror on a global scale, in addition to a lot of unsavoriness in my own personal life, induced in me a yearlong craving for sensory obliteration that I mostly addressed by blasting Brat. Not a few other chaotic records also made a dent in me: Icelandic composer Bára Gísladottír and flutist Björg Brjánsdóttir’s GROWL POWER (Smekkleysa), whose title track concludes with Brjánsdóttir simultaneously flute-ing and woofing at the top of her lungs, a cathartic listen for humans and hounds alike. Another find for me was the supermassive guitar choruses of Joshua Chuquimia Crampton, who has a record from this year (Estrella Por Estrella), though I was more taken by 2023’s more eclectic Profundo Amor (both records on Puro Fantasia Music). The mere existence of the deliriously polymathic Australian violinist Jon Rose fills me with joy, and I found many rewards in his record Band Width (Relative Pitch Records), an improvisation with bassist Mark Dresser that manages to be both vigorous and lackadaisical at once.

Even a lot of the quieter music I liked in 2024 had some secret thrashiness: the record House of Gold (SOFA), an ensemble project by Isaiah Ceccarelli, features the track »Terre noire«, which begins as lapidary two-part singing joined by synthesizer organs, and then, out of nowhere, nonchalantly drops the beat. It’s my favorite transition of the year. Maybe my most chaotic record moment of all for me, though, was last week at my friends’ apartment, when one of them dared to put on a vinyl of Conlon Nancarrow’s player piano studies; it’s remarkable that we managed to complete a single thought with those cursed carnival tunes in the background.

Did you find your own listening habits transform this year (a diagnosis that ideally one can assess without Spotify’s strongarming)?

Andreo:

Electronic music past and present has been on my mind lately. I was proud of a miniseries that Seismograf, the Polish magazine Glissando, and the German Positionen published this December on what would have been the Danish electronic composer Else Marie Pade’s hundredth birthday. We also pointed to Eastern European female pioneers and discussed what a canon really means today.

Which electronic music caught your attention this year?

It's more than Turkish psychedelia – it’s the sound of a big rumbling world

Jennifer:

I was so happy to see that collaboration. I particularly liked Sune’s pointed dissection of how Pade has been narrativized and re-narrativized, which takes a committed insider to compile. Someone said to me recently that festival collaborations are the future, and potentially magazine collaborations as well if we keep our fingers crossed.

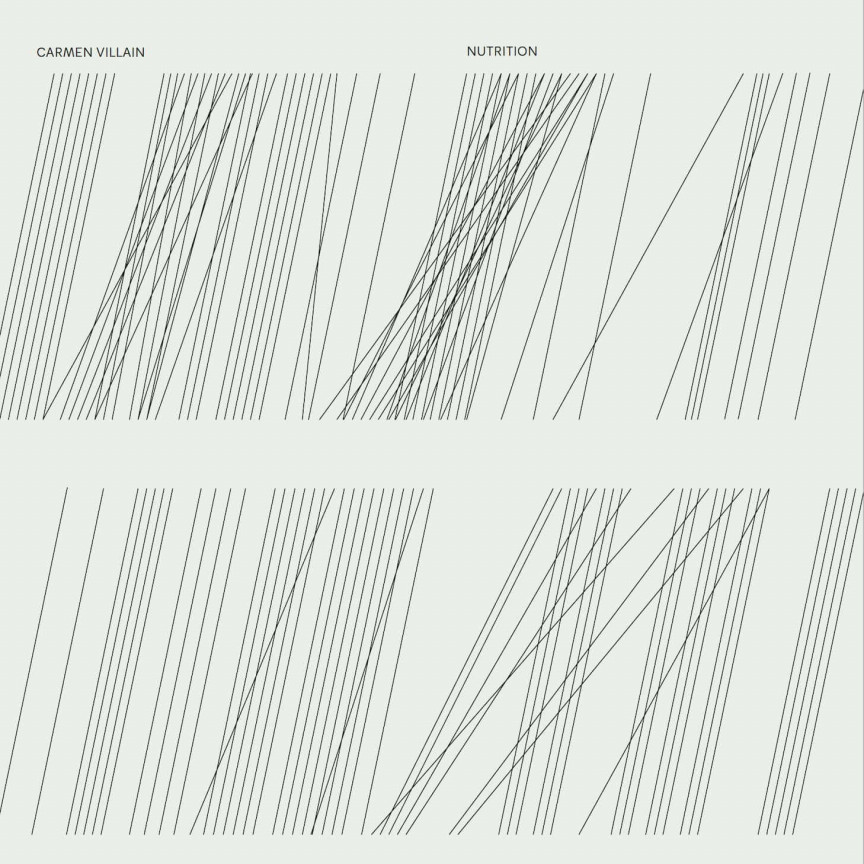

Electronically. I’ve had my eye on the musician Elvin Brandhi, whom I first heard at Borealis Festival in Bergen, Norway, and so was pleased to discover Pollution Opera (Danse Noire) in March, a collaboration between Brandhi and the musician Nadah El Shazly that concatenates field recordings from a Ugandan residency and El Shazly’s native Egypt with exclamations of noise and song. Another highlight was Carmen Villain’s Nutrition EP (Smalltown Supersound), which lends her lo-fi nocturnalism an addictive dubstep undercurrent.

In person, I was very taken with a set by Jessica Ekomane at this year’s OnlyConnect Oslo in the spring. She has an acute sense of flow and structure, and the setting of Majorstuen kirke couldn’t have been more prime for the listener who wisely laid on the floor and let the sound sync with the ceiling, which turned out to be painted a child’s vision of heaven – freely doodled stars, floating in splotches of blue.

Andreo:

Yes, Ekomane was like very slow techno made of fine dust. At the same festival, I heard the recently deceased American-German composer and visual artist Gloria Coates' Symphony no. 1 – Music on Open Strings (1972) – wow, so many frictions and inward dramas expressed in quiet and microtonal bursts. We were about to do an interview with Coates in Germany, but unfortunately she died shortly before.

Jennifer:

Coates discusses in this 2008 interview how her ‘70s electronics experiments trained her to more keenly perceive microtones, which, she believed, went on to inspire her approach with orchestral works, of which Music on Open Strings must have been one. I loved the orchestra returning to usual tuning in the latter half – a progression of tectonic cranks – and the gravelly miasma of the whole group playing on the lower strings that starts off the final movement.

But Jennifer, tell me: is Brat still big in New York?

Andreo:

The world might be getting increasingly electronic, but some are going the opposite way. Pianist and composer Simon Toldam often plays on electric keyboards, but on Fem Små Stykker Med Tid (Five Small Pieces with Time) (ILK Music) – the music can be found on a completely transparent and beautiful vinyl – he only uses an acoustic piano. The sounds strolls away so slowly. Another amazing piano album that stopped time for me – or showed me different aspects of time – was Kristoffer Hyldig’s Olivier Messiaen: Vingt regards sur l’enfant-Jesus (OUR Recordings). So many Aarhus bands are doing this meditative-piano-beauty seeking stuff, such as Lars Fiil’s recent New Ground (Fiil Free Records). The best example of this is Aarhus-born Jakob Bro and his New York friends’ Taking Turns (ECM). Brilliant!

Are we all seeking more pauses in our flickering lives?

Jennifer:

I can only speak for myself and say that I’ve been after focus more generally, but, importantly, I am trying to arrive at that focus through joy, rather than by bullying myself out of distraction. I think, in a disintegrating system, the time is now to love what you’re making. I find it all too easy to devolve over my own creative missteps as a performer, but then sometimes I’ll go to a concert that reminds me what terrible actually is, and I'll realize that I’m maybe not so bad after all. This is a really motivational kind of schadenfreude. But I think the real question of whether continuing is worthwhile is less how you perceive the quality of your work than whether you like doing it.

What other disciplines or media have you enjoyed this year? Have any of your musical experiences led you towards something you might not otherwise have encountered?

Andreo:

I heard a tenor singing in the mountains at the Bergen Festspillene. The sounds evaporated in the air because opera is not made to be sung in such a high altitude.

The highlight at the Spor Festival in Aarhus was, for me, Kaj Duncan David playing his work Only birds know how to call the sun and they do it every morning. The Berlin-based composer, who is interested in consciousness and artificial intelligence, says about his album: »The little child is still open and sees the world as wonderful. I wanted to celebrate that.« These 11 songs respirated.

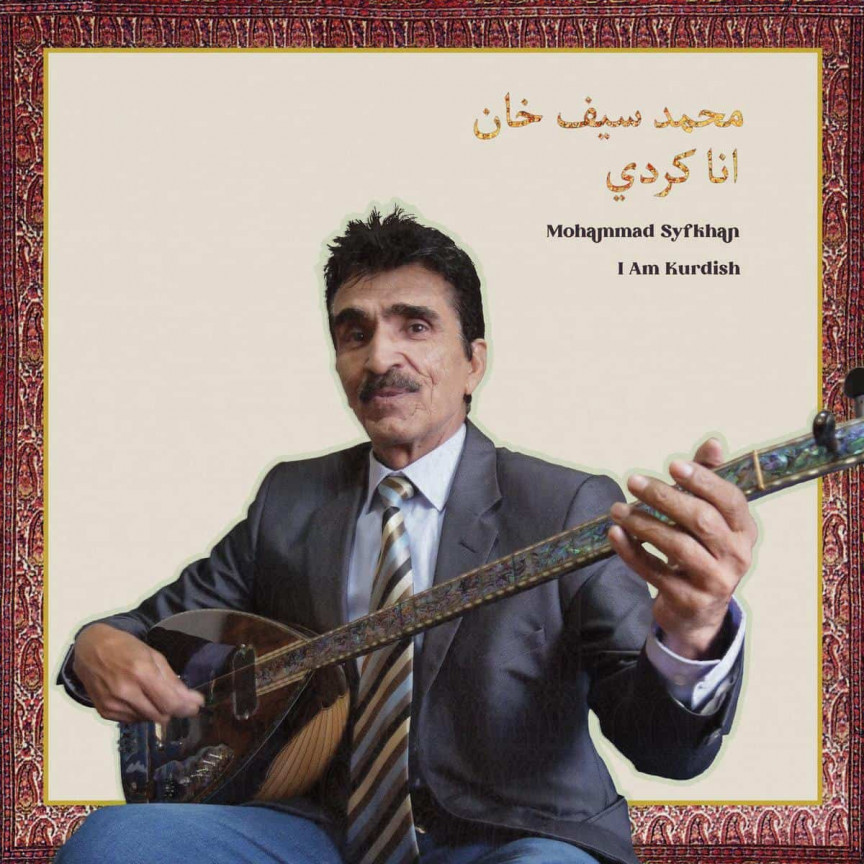

I heard similar fragilities mixed with a post-apocalyptic atmosphere on Dialect's album Atlas Of Green (RVNG Intl.). And Mohammad Syfkhan made my world bigger with I Am Kurdish (Nyahh), which also features Irish saxophonist Cathal Roche. It's more than Turkish psychedelia – it’s the sound of a big rumbling world.

I also loved the blend of Hildegard von Bingen and Ukrainian folk music in Ukrainian composer and musician Heinali and flautist and singer Yasia Saienko’s project Гільдеґарда (Hildegard) at Unsound Festival in Cracow. I’ve been following Heinali since I stumbled on his performance in a bomb shelter in 2022.

And the beautifully brutal echoes of folk music on Sealionwoman's album Nothing Will Grow In The Soil (The state51 Conspiracy). Looking forward to hearing them in Berghain in Berlin in January.

But Jennifer, tell me Is Brat still big in New York?

Jennifer:

Though I moved back to New York in September and missed the summer wave, my situation was such that I had a bratty summer of my own anyhow. I was living in Sweden at the time, and Charli XCX mentions being in Stockholm to see a friend on »I think about it all the time« – I was in Malmö, but if you squint and completely forget where you are, it’s the same? The last two years have also found me living rather internationally, and a lot of the lyrics concern the transience of celebrity life, not that celebrity was motivating my travels in the slightest – just, sometimes I would be en route to CPH to the tune of »Apple« (»to the airport«) and sometimes I was in CDG wondering if I was in the terminal where the music video for Von Dutch was shot. These are just a few of the obnoxious truths of my recent life that I’ve been lording over my fellow Americans, make no mistake.

Torvund is the most skillful architect of musical delight I know

It would nevertheless have been fun to have been closer to some Charli epicenter, just because a movement like this around an album with actual streed cred doesn’t come around all that often. I tend to be severely allergic to the zeitgeist and am glad to have overcome myself on behalf of this phenomenon that ultimately brought me back around to pop.

Did you find any music that helped you hear a genre with new ears?

Andreo:

I had one such disorienting experience in Norwegian composer Kristine Tjøgersen’s magnificent orchestral work Pelagic Dreamscape, which is full of insect tickles and oxygen bubbles. I also enjoyed how trombones, birds and electronics form an orchestra for the future in Rafael Toral's Spectral Evolution (Moikai), and how Radical Polish Ansambl takes old traditions into the future on Nierozpoznana wieś. And how Warsaw Village Band creates vitamin-rich trance on Sploty.

One of the bravest albums of the year was Ex-Easter Island Head’s Norther (Rocket Recordings), in which post-minimalism lives on. I also think it’s fascinating what the Los Angeles musician Tashi Wada did on What Is Not Strange? (RVNG Intl.) – making music using an 18th-century tuning system developed by music theorist Jean-Philippe Rameau.

What about one of this year's other trending art words – immersion?

When a few thousand people clap their thick mittens in minus 30 degrees, it sounds like the softest techno

Jennifer:

I’ve been particularly interested in immersion that functions as a kind of accessibility, in performances that don’t privilege a single vantage point such that the listener can stand, sit, lie down, move about, take in the show however they are able. The post-pandemic era in live music has indulged a fantasy in which some of the accessibility provisions imposed by global lockdowns were exclusive to 2020, but clean air, livestreams, alt text, and mutliple seating arrangements, among other provisions, are only going to be more important as the consequences of Covid normalization continue to bear down.

That said, music with an immersive aspect found its highest exponent for me this year in Øyvind Torvund’s Symfoni for Grieghallen, presented at this year’s Festspillene in Bergen, Norway. Torvund is the most skillful architect of musical delight I know, of which this performance was yet more evidence. The sections of the Bergen Philharmonic were distributed into different spaces within Grieghallen – strings in the foyer, brass in the auditorium, percussion by a stairway, and so forth – and the audience was to wander around the space, collaging the symphony per where they elected to go. I have rarely seen people so gleeful at the concert hall, and how could you not have been, trailing the music through empty auditorium aisles or around banquet tables or up and down stairs to hear the music anew depending on where you were and what instruments you were near. It was a much-improved restaging of its predecessor, Symfoni for Kunstnernes Hus, which I saw in the eponymous gallery in Oslo in 2022 and liked, but Grieghallen was the far more suitable space, both more apt and obviously better built for sound. We were all at play, the musicians and the audience alike.

Andreo:

For me, Bach also proved to be highly immersive: J. S. Bach: Six Suites for Cello Solo by Henrik Dam Thomsen (OUR Recordings) got under my skin. And if Bach's music was sacred geometry, Thomas Agerfeldt Olesen's Piano Works (Dacapo Records) is poetic geometry for two hands on a piano. On this very old instrument, the sounds feel so vital. And, suddenly, the pianist Rolf Hind begins to speak over the music.

What was your wildest experience with sound this year?

I couldn’t square how he’d coerced the yoga ball-bagpipes to emit those moans

Jennifer:

This distinction easily goes to a set I was very lucky to catch at Geneva’s Archipel Festival by the musicians Arthur Chambry, Ragnhild May, and Lukas de Clerck, who presented interconnected solo sets united by the splendor of aeration. That is to say: May walked around the room connecting prepared recorders by tube to a device that pumped air into the instruments, producing over many minutes a squealing drone chorus that invaded my every pore. She herself proved unshakeable, her expression impassive throughout a long methodical process of stepping over, and occasionally on top of, the giggling audience members whose bodies obstructed her course to the next recorder.

I think of Chambry’s set often, as it is among the most incredible performances I have seen in a long time on account of its sheer weirdness and musicality. He began by inflating a yoga ball that he eventually strapped to his back, and which was outfitted with two drone-emitting pipes beside each hand, which he adjusted to manipulate pitch. I couldn’t square how he’d coerced the yoga ball-bagpipes to emit those moans, that ramshackle creation that, from the face of it, shouldn’t have been capable of anything but crumbling at a moment’s notice – and then came his committed, even desperate vocal performance on top of that, this searing chant, a song to herald world’s end.

Andreo:

Yoga ball-bagpipes to the end of the world! Cool.

Jennifer:

Yes, it was bananas. Then de Clerck inflated a bouncy house that had likewise been bewitched into a life of drone manufacture, and the three musicians joined to drag out of it what was assuredly the performance of its lifetime.

At the top of my New York sightings following my move back in September were two performances at the Brooklyn venue Cutelab – the first by Levi Lu, whose set involved using a laptop itself as an instrument, bowing on the metal sides and shaking the keys, and climaxed with Lu manipulating a flight controller worn in the style of a dildo, for a ridiculous crash of body and sound and self-examination that did one better than the usual experimental set by making everyone laugh.

The second was on another night by the duo elekhlehka, whose set, drawing upon gong traditions in Southeast Asia, was an impressively smooth meld of live coding, electronics, and audience activation – at a certain point we’d all been given makeshift gongs to thump at our own pace – that informed upon a complex history.

I was additionally very taken by a performance at Blank Forms by violinist and composer Keir GoGwilt and composer and musician Celeste Oram, who tempered an otherwise blustery day with warm, lightfooted songs, delivered with skill and clarity.

Your turn – any 2024 performances that reign in your mind?

I wanted to half-scream and make clicking noises back at the skinny American

Andreo:

Oh, we really need humor. In a theater in Copenhagen, the 81-year-old vocalist and composer Meredith Monk spoke about our complex world – including the wars we don't hear about, even though they are making noise. With her breathing and abstract vocals, Monk mimicked the world's smallest animals while moving with the ease of a Japanese kabuki dancer. It was fun. So typical of Monk to hold the microphone to all sentient beings, instead of ignoring them. And it was as if the sounds came at once from ancient times and from the future. I like that she looks with a magnifying glass at the world and the sounds around her and transforms them all – almost one to one – into singing. I wanted to half-scream and make clicking noises back at the skinny American.

The world's oldest instrument – the human voice – can still express stories and moods that defy the logic of language. Vocalist Randi Pontoppidan makes this clear on the album Hippo Road (Time Span Records) with Thomas Agergaard (sax) and Greg Cohen (bass). And the very old art form opera can still be shaken, as Simon Steen-Andersen showed us in Don Juan’s Inferno.

But my wildest experience was the Barents Spektakel festival in Kirkenes – just a stone’s throw from the border to Russia and Finland. When a few thousand people clap their thick mittens in minus 30 degrees, it sounds like the softest techno. In the city of Kirkenes they have a bivouac, a couple of churches, and a cultural festival. They are prepared if the worst happens.

Jennifer:

Barents Spektakel does strike me as an incredible festival, I’m supposing with few or no parallels. I also certainly agree about the value of humor as well, or at least a healthy lighthartedness. It’s good to blink a few times a day and remember that music is ridiculous. I’m still amused by a memory from this year’s NyKlang program at Klang Festival, featuring students from MGK (the pre-college music academy Musikalsk Grundkursus Hovedstaden), who had staged rambunctious group performances across the grand rooms of the repurposed museum Musikhuset København. I stood on line for some time to hear one project that was located in a room that was down a far hallway, though with some apprehension, as earlier we’d heard someone scream and we had yet to find out why. When it was my turn, I was led to a large room containing just one singer, embodying the perfect posture and guileless professionalism of a choir boy, who showed me to a chair in the middle of the room. He picked up a small paper containing his score and sang a beautiful song of around a minute, and, when he was finished, proceeded to push the score into a shredder. »You’re the only one who is ever going to hear that,« he said, looking a little apologetic. Which is the fate of a lot of contemporary music – something to scream about, sure.

Hey, drone music never gets old or even tired

Andreo:

Everybody applauded when the French flutist Emmanuel Pahud received the Sonning Music Prize and played Carl Nielsen all over Denmark. The Danish composer Rune Glerup received the Nordic Council's Music Prize for his work About Light and Lightness, and, a few days later at the Nordic Music Days in Glasgow, he shared some interesting reflections on what the Nordic really is. »Music is just music, no matter where the music comes from,« he said.

That Nordic sound has also been called The Northern Silence. Is it really? You work between Scandinavia and the US – isn’t all blurred today?

Jennifer:

A few themes come to mind for me regarding Nordic new music: the playfulness, eclecticism, popular music-influenced tonality, earnestness, and spaciousness that I often hear in the music itself, and also the infrastructural provisions, public funding system, and flatter socioeconomic and cultural hierarchies that allow artists to live and work in ways that are usually not possible without wealth. I’m deeply interested in what these privileges allow people to dream up, and grateful to have benefitted from living in places where the arts count for so much. I’m also much more appreciative than ever before of everything that gets done under greater limitations.

Which Nordic records or performances struck you the most in 2024?

Andreo:

I still listen to viola player Pauline Hogstrand’s Áhkká (Warm Winters Ltd.) from last year (hey, drone music never gets old or even tired) and keep noticing new dynamics. I was also shaken by Søs Gunver Ryberg’s Coexistence – perfect mix of electronics and orchestra – and the Siemens Composer Prize winner Bára Gísladóttir’s Orchestral Works (Dacapo Records) with the Iceland Symphony Orchestra. »You can almost feel the nerve gas seeping into the lungs with the trill of the whistles. The oboes blare and the cold sweat billows. Welcome to the seething core of the Earth,« wrote our reviewer Jakob Gustav Winckler.

I’ve had a lot of flute optimism in the last many years

Jennifer:

Gísladóttir’s impressive pieces spooked me to a degree I didn’t think was possible in merely playing something off my laptop speakers, so I can only hope an orchestra does them in New York sometime and scares the bejesus out of me properly. I’ll add to your list Kristine Tjøgersen’s Between Trees (Aurora Records), which prompted in me rather a different reaction – unbridled joy – but is not unrelated to the Gísladóttir record in its mission to dig new life forms out of acoustic instruments.

Andreo:

One of the big surprises last November was that the rapper, actor and OutKast musician André 3000 started playing the flute. Could it get any more absurd?

Jennifer:

I’ve had a lot of flute optimism in the last many years, instigated by Claire Chase’s Density 2036 project, which made me think that the instrument might be the future, and power to Mr. 3000 if he wants to be a part of that. In seriousness, I imagine that it can be difficult to try new things as an artist of that prominence, so I can only applaud his efforts to do what nobody was expecting, and what maybe some people might even view as a misstep. At worst it’s an EWI awareness movement.

Has another musician surprised you like this in recent memory?

Andreo:

Not so radically, but the Danish viola player, singer and producer Astrid Sonne made a very important statement with her album Great Doubt. Seismograf's Rasmus Weirup wrote that Sonne's viola sounds with »such a powerful presence that it almost sounds like a deeply complex living organism that breathes, feels and moves dramatically through the album's nine songs.«

Let’s have more techno-romanticism. Let’s dance

Jennifer:

Seconding your comments about Sonne, whom I’m very excited to see live when she comes to New York in March. I’ve been on her beat since 2021’s outside of your lifetime, as the part of me that was raised by the Suzuki method is apparently still primed to click on an electronic music track named »Moderato«.

Andreo:

In the future we should have more flutists, Suzuki players, and artists like singer-songwriter Sufjan Stevens who dare to work with classical orchestras, and more composers who go on stage to sing or just take risks. The new Copenhagen Minu Festival showed, again, how far we can go with music. And Jennifer, before I go I’ll ask you to listen to the majestic hyperpop-like synthesizer grooves on NEKO3's brand new recording of Alexander Schubert's Angel Death Traps (Don’t Look Back Records) – it’s a song cycle investigating the digital and the human.

Let’s have more techno-romanticism. Let’s dance.

Jennifer:

Yes, I think our present musical moment is extremely amenable to people somersaulting out of their lanes, so by golly, guys, just go for it. And seconding your injunction to dance – now, more than ever!